Power, Money and Stability

The Bank of England, the central bank equivalent to the Federal Reserve in the USA, declares: “Money is a kind of IOU which is universally trusted.” But this is not always true, and from this comes a question which has occupied thinkers throughout the history of money: What are the conditions in which such trust can occur?

Ancient Chinese Money Theory

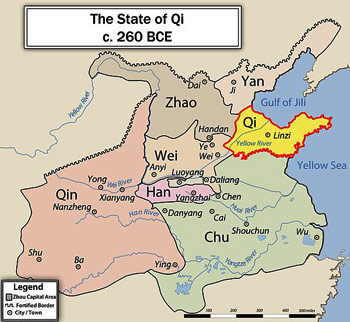

In the 4th century BCE, the Chinese came up with a clear answer which influenced their administration right up to the 20th century. At the height of the Warring States period, Duke Huan of Qui invited the foremost thinkers of his age to advise him on how best to govern the country and defeat his enemies. The think tank he established was known as the Jixia Academy, and it developed monetary theories which were set out in a collection of writings called the Guanzi, a work which attained near canonical status for the next two thousand years.

In Money: The Unauthorised Biography, Felix Martin writes “Money, they wrote, is a tool of the sovereign – part of his machinery of government: ‘[t]he former kings used money to preserve wealth and goods and thereby regulate the productive activities of the people, whereupon they brought peace and order to the Subcelestial Realm.’

“…the Jixia scholars developed a simple but powerful theory of money. First of all, the value of money, they explained, was unrelated to the intrinsic value of the particular token used: ‘[t]he three forms of currency [pearls and jades; gold; and knife- and spade-shaped coins]’ … Instead, money’s value was directly proportional to how much of it was in circulation compared to the quantity of goods available. The role of the sovereign, therefore, was to modulate the quantity of money available in order to vary the value of the monetary standard in terms of those goods…”

Modulating, or varying the quantity of money could serve two purposes: “First, it would provide a powerful means of redistributing wealth and income amongst the sovereign’s subjects, as inflation eroded the claims of creditors and eased the burden of debtors, shifting wealth from the former to the latter – or deflation did the opposite. …the most important redistribution, if new money were minted, would be to the sovereign from his subjects as he spent new money into circulation at essentially no cost…” This gave the sovereign the same privilege for monarchic profit which we call seigniorage in the Western tradition.

“Second, it would regulate economic activity by making the primary instrument for the organisation and settlement of trade… readily available. The goal of government should be a harmonious society, and monetary policy was a powerful tool with which to achieve it. …[but] there was a catch. For money’s powers to be effective, the Jixia scholars pointed out, the sovereign must retain exclusive control over them. If anyone else in the kingdom was able to issue money, then they would arrogate to themselves control over the value of the standard, and usurp part of the sovereign’s power.” And occasionally others did gain control of the state’s money supply, with disastrous consequences for the stability of the state.

“… Whoever wished to remain in power and see his domain well governed should jealously guard the management of the monetary standard and the monopoly of issuance. As the Guanzi put it, ‘[t]he prescient ruler grasps the reins of the common currency in order to bridle the Sovereigns of Destiny’.”

Thus the Guanzi was a recipe for a rigid, hierarchical society, with a monarch at the top, and these ideas about government remain essentially static in Imperial China for well over two thousand years. Other cultures fared differently.

Roman Money

The Romans, whose republic was a militaristic oligarchy with a touch of democracy, and whose expansionist Imperium later stretched right round the Mediterranean, were less clearheaded about the role of money in the state. Their financial infrastructure was vast and complex. But unlike the Chinese, it was not founded on a clear theory of money as a tool of the ruling class. Instead, Aristotelian ideas held sway, and these only dealt with the fairness of exchange, not with the stability of the monetary system, or its political repercussions.

The only agreement they had with the Chinese was about the inherently unequal status of individuals: that it is completely natural for people to be unequal, that society is formed of a natural hierarchy. That the aristocrats should be rich and powerful, as of right, and the slaves they owned, powerless, like cattle.

The Roman government never looked on money as a means for stabilising the state, and though it lasted for hundreds of years, its stability required constant expansion and conquest, inputs of wealth from outside.

There was of course a trusted coinage, but as in any sophisticated monetary economy, coins were principally used for minor transactions, for taxation and the payment of soldiers, for war (war which would bring booty, tribute, land and more slaves). Large payments were made not by coin, but by promissory notes or bonds. And, by the time of the Imperial age, wealth was held not just in land and slaves, but also in money, out at interest – making the rich ever richer. Usury was the order of the day, and many rich men spurned real assets, preferring to deal in money and receive interest.

Then, as now, financial finagling caused credit crises, times when long term lenders could not repay their short term creditors. For instance, in 33 CE the property market collapsed and there was a fire-sale of mortgaged land to fund repayments. Mass bankruptcy threatened to engulf the financial system. Ultimately there were bailouts for the rich lenders, just as now, and the system only survived by Imperial decree, by a government issue of more, diluted coin.

As the Power of Rome Declined, Money Dwindled and Died

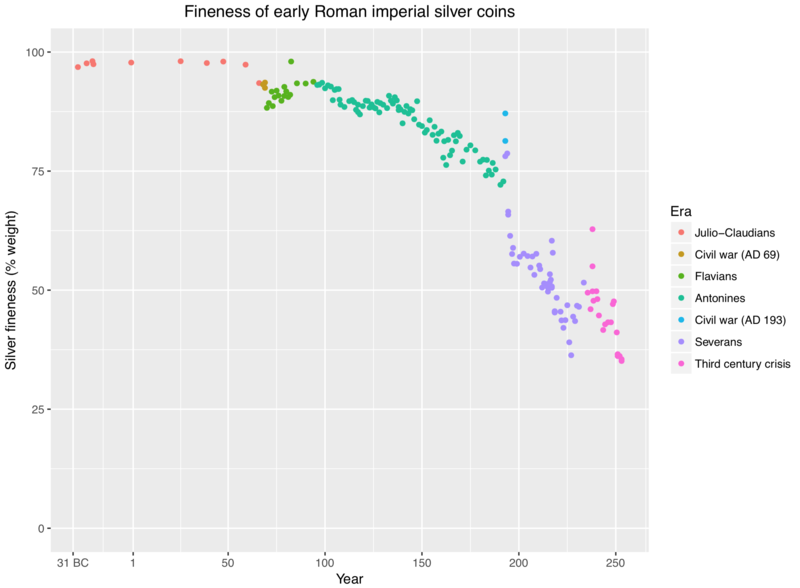

But in the end, Imperial decree, or fiat, was not enough, for as the Emperors progressively debased the coinage, using cheaper metal or less of it per coin, money did not hold its value. There was inflation, and at the same time the Empire became less powerful. According to Felix Martin: “As the military and political might of Rome declined, so did its rich financial ecosystem. In the late third century AD, as Rome’s prize possession of Egypt passed in and out of foreign hands, there was serious monetary disorder, including an inflation in AD 274–5 when prices rose by 1,000 per cent in a single year.

“After AD 300, bankers disappear from the records – the social and political stability required to underpin professional finance had, it seems, disintegrated. As the institutions of government retreated from the outer reaches of the empire, so, largely, did the institution of money. The effects were most severe in the most remote and marginal colonies. In Britain, for example, the Roman monetary system disappeared completely within a generation of the departure of the legions at the beginning of the fifth century AD.

“For a full two hundred years, coinage was forgotten as a means of representing money despite having been in constant use for nearly five centuries before then. Eventually, all over Europe – even in Rome itself – the splendid sophistication of monetary society faded away. Like Greece after the fall of Mycenae, Europe entered its own Dark Age –an age that saw a near-total regression from monetary to traditional society.”

Economic activity cannot flourish in a world of anarchy. Money needs trust; trust in the future, trust that political power and the environment will not change, trust that others will be able to pay, that contracts will be honored, that they will be enforced by lawful authority. There has to be social stability, and that stability had been provided by something that existed no more, the military and institutional power of Rome.

The Rebirth of Money in Europe

It was not until Charlemagne set up the Holy Roman Empire in 800 CE, that money began to reappear again in Europe. And even then it was more of an assertion than a reality. Charlemagne brought some order to his realm, and laid down that money should be denominated in Pounds, Shillings, and Pence. But there were not many coins to be found. Economic relations still consisted largely of tribute; tribute owed up the feudal hierarchy. It took another 300 years until feudal tribute and the corvée, under which the lord’s vassals had been expected to provide service for a number of days each year, began to be supplanted by monetary payments.

By the 12th century these feudal obligations, traditionally payable in kind, began to be transformed into fiefs rentes– rents payable in money. Here and there officials began to be paid in cash, and taxes again began to be levied. A commercial society of sorts sprang up, growing in the Burghs, the walled towns which became refuges for the Burghers who had fled the depredations of the feudal lords. Often there was conflict between the feudal lords, who held the land, and their king, whose mint issued the money. And it was these Burgers (later known as the Bourgeoisie), who learned to deal in money, and often were protected by the king as a bulwark against his lordly magnates.

The King’s Money and His Seigniorage

As it was the sovereign who minted coins, this gave a ruler the opportunity to make a profit. This profit, the difference between the nominal value of coins and their cost of production, was called seigniorage. It can be thought of as a hidden tax, the crown’s opportunity to take a percentage on the bullion brought to a mint for coining.

The Romans of old had debased the coinage to make more of it available, and now again, in medieval times, it became a common practice for a king to call in the coin and reissue it in a lighter form, for instance “the re-coinage of 1349 generated nearly three-quarters of all revenues collected that year by the king. When such large sums could be raised, it is hardly surprising that there were no fewer than 123 debasements in France alone between 1285 and 1490.” Also, as medieval coins were minted without a mark of value, the king could just issue an edict proclaiming that the value of a coin had been changed.

So when kings needed money to pay for war or splendor, they often inflated their treasuries by diluting their coinage, and as coins were the only technology representing money, their hapless subjects had no option but to suffer the reduction of their wealth this caused. Naturally, the merchant classes, who were expanding in the Burghs, resented this and sought out ways to stabilize the value of their money. One of the ways they did this was by developing a private money of their own, alongside the official money of kings.

The Rebirth of Banking and the Birth of Book Money

This private money was used for international trade, and did not exist as coin, but only as a notional money-of-account, book money, called the écu de marc. This was the notional money invented by the merchant bankers of the late middle ages in Europe. It was used for accounts in long distance trade, for instance between Flanders, in the North of Europe, and Italy, many weeks travel away in the South. But it was not common currency, it only appeared in the merchant bankers’ account books.

If you were a merchant in Italy, buying wool from a merchant in Flanders, it was not prudent to send coins which could be easily stolen on the way. You also needed to be confident that payment would be made correctly. And you did not know the distant trader well enough to trust that he would pay you. But you could rely on an intermediary, a new kind of merchant who dealt in credit and who everyone knew and could trust, the merchant banker. These bankers issued a new kind of financial instrument, originally used in 8th century China, the bill of exchange, which was good for payment to someone you did not know, in a currency with which you were not familiar.

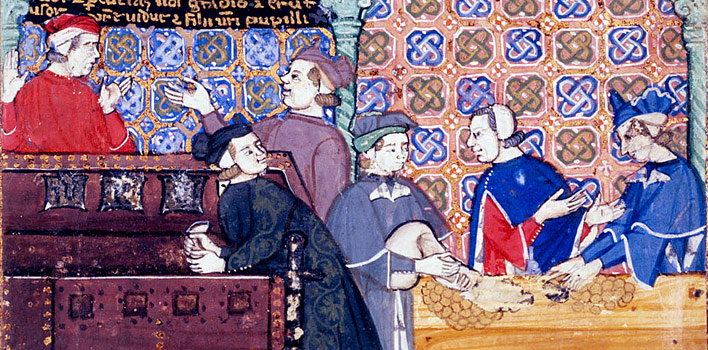

The merchant bankers would charge a fee for their service in issuing and redeeming these bills, which acted as a kind of paper money, but was restricted to the bankers’ dealings. These bankers constituted a tightly knit group who met regularly at the great trade fairs, in towns like Lyons and Champagne, where they would redeem the bills of exchange among themselves and balance their books, using the écu de marc as their private currency.

There was a three-way exchange. The king’s money in one country was valued against the écu de marc, which in its turn was valued against the king’s money in another country. But no coins were ever seen in these transactions. As a French official wrote in 1604, it was not unusual to see “a million pounds paid in a morning, without a single sou changing hands.” By balancing account books at their regular meetings, payments were made securely between the bankers, and they grew immensely rich in the process of transacting business across borders.

Usury, Loans and the Creation of More Banker’s Money through Debt

But this was not enough for the bankers. They knew that they could make more profit by lending money at interest. However, here they came against a barrier: faith in religious teaching. The teaching of the Christian church, of Islam, and of Judaism forbade usury, the lending of money on interest, particularly for items of personal consumption. They prohibited this for the very good reason that it leads the poor into terminal debt and poverty. Indeed, from ancient times there had been periodic forgiveness of debt, devised to rebalance human relations. (In modern economic terms, they recognized that producers depend on the consumers having enough money to buy their goods. So they must not be allowed to become terminally poor).

However, Judaism permitted Jews to charge interest to people outside their community, thus allowing Christians to evade the restriction by borrowing from Jews. Useful as this was to both sides, it is one of the factors that exposed Jews to continuous envy, hate and persecution.

But as time went on in Europe, the religious restriction on usury was relaxed. To begin with, interest on loans was disguised as fees, and later on, particularly after the Reformation of the 16th century, lending on interest became more and more acceptable, particularly for mercantile ventures or for war which brought in booty.

This relaxation of the prohibition of usury gave bankers the opportunity to enter a new realm of profit. At last they could create more private money by the very process of accepting deposits and providing loans; what we now call fractional-reserve banking.

Fractional-Reserve Banking and the Alchemy of Money Creation

The process works like this: a saver who wishes to keep his money secure, and at the same time earn some interest, can deposit it with a banker (originally it was deposited as gold or silver coins). Then someone who wants to borrow money can do so by entering into a contract with the banker, ceding control of some property as collateral in return for the loan, and the payment of interest at a slightly higher rate to cover the banker’s expenses and profit, the rate depending on how risky the loan is (here the banker gambles that he can assess the risk correctly). As not all the savers who have deposited their money will be likely to take it out at the same time, the bankers depend on the expectation that it is usually safe to lend out more than they have taken in.

This smaller amount of savings is the fraction that the bank holds in reserve, in the expectation that it will never need to pay back an amount equal to the total amount that it has lent (originally this was in the ratio of 5:1). However, if the depositors ever suspect that the bank cannot pay them if they demand their money, they will all demand to be paid immediately, and the bank will run out of money. It will be bankrupted. Fortunately (or unfortunately) this did not happen often, so the inherent vulnerability of the system is not often tested. For it is a system which relies on the credibility of the bank, on confidence – a kind of scam.

This greater amount that is lent out constitutes the private money which the banker has created, in effect out of thin air. As this was notional money in the bank’s ledger, it did not need to be handled as specie, as metal coins. But this notional money did fund more commerce, and gave a big boost to the expansion of the economy. Even though it was a fiction, existing only in the account books of the merchant bankers, it added to the amount of capital available, and funded the accelerating growth of the capitalist system. A system that funds the present by borrowing from an uncertain future; an act of faith.

The Bank of England: The First Longstanding Central Bank

In the 17th century, as before and since, there was often greater demand for money than there were coins available, and privately issued local tokens often appeared. Another old problem was that the king’s government, which had defaulted too often, was unable to raise sufficient loans to fund its military spending. This came to a head in 1688 when the protestant William of Orange came to the throne of England with his wife Mary, daughter of the ousted king James. William’s native country was protestant Holland, and it was at war with the Catholic king of France, Louis the XIV. William and Mary needed money for the British navy to pursue that war, but the king’s government could not be trusted to repay a loan.

In 1694 a group of merchants from the city of London came up with a plan to fund this war. They proposed that a central bank should be formed, similar to the only previous central bank, the Swedish Riksbank which was founded in 1668, but not allowed to issue notes. This was to be a private bank called The Bank of England, which would lend money to the crown to fund the war.

In return, this private bank, funded by deposits from city merchants (who were paid interest at the rate of 8% on the money they invested), would be backed by the government of England and also empowered to issue paper currency. Though these new banknotes could be exchanged for metal coins at the bank, they became, in effect fiat money, backed by the wealth of the whole population of England.

This bank and its currency still exists, and thus arose the first longstanding central bank empowered to issue the first longstanding paper currency in Europe, with the first national debt to private individuals. A government debt that is backed by the tax that could be collected from all the people of England, and the booty of war.

Fiat Money Created by Commercial Banks

So it was that a king’s government privileged a few individuals to transform the original idea of the bill of exchange into a legally accepted form of fiat money; the paper currency which we all use today, banknotes.

Other forms of paper money have at times been less long lived. In 1716, the Scotsman, John Law persuaded the French regent to allow him to form the Bank Générale Privée. This bank was empowered to issue banknotes, but unfortunately these became linked to a vast speculative venture, the Mississippi Company, and when that speculative bubble burst in 1720, the value of the banknotes collapsed, leading many people to conclude, quite wrongly, that paper money can’t be trusted—a conclusion that persisted for a long time thereafter.

But John Law had been correct in principle when he issued notes without relating their value to gold and silver. For he argued that: “Money is not the value for which goods are exchanged, but the value by which they are exchanged.”

In Colonial America, short lived bills of credit were issued by colonial governments to pay debts; a currency which the governments would then retire by accepting the bills for payment of taxes. Such bills were also issued occasionally throughout the 19th century. It was not until 1861 that that the U.S. government issued the first greenback – notes that were legal tender – government money to pay for war. Before that, the only legal tender was gold and silver coins, though banknotes were issued by commercial banks, which were meant to be redeemable for coins at the bank. When these banks failed, as they often did, the banknotes could not be redeemed.

Now most countries have central banks of one kind or another, like the German Deutsche Bundesbank, or the American Federal Reserve bank (created in 1913, in response to the crash of 1907 as a “lender of last resort’” to support the unstable commercial banks). The existence of a central bank as the lender of last resort produces a situation in which the commercial banks are encouraged to take undue risks, knowing they will be bailed out if things go wrong, which is called “moral hazard” in the trade. So, as occurred in the financial crisis of 2008, their profit is privatized and the result of their risky behavior is paid for by the public – a sure way of transferring wealth from the poor to the rich.

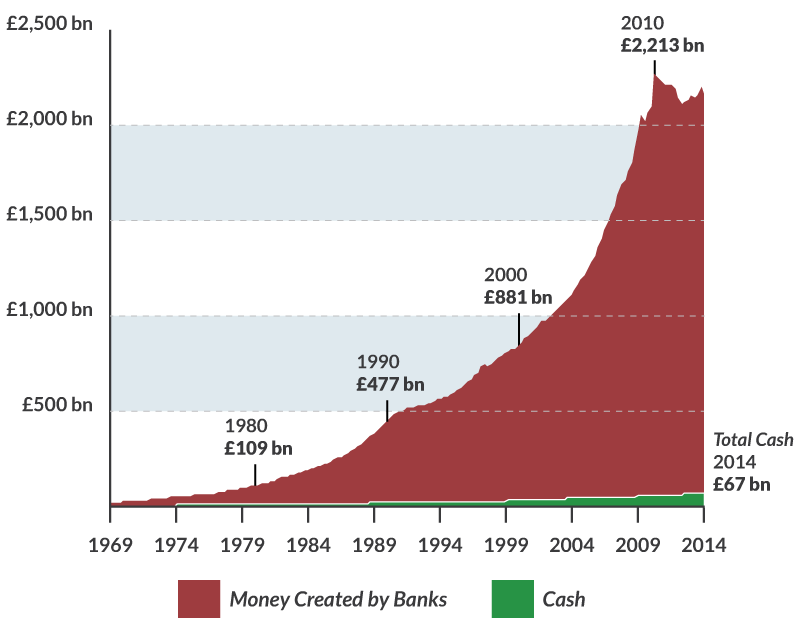

Because any commercial bank is free to make a loan and collect interest, most of the credit money in circulation in the Western world is actually produced, as if by magic, by private banks. In fact, the recent Governor of the Bank of England, Mervin King, stated in 2017 in his book The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking and the Future of the Global Economy, that between 90% and 97% of all money around the world is created by commercial banks and only 3% to 10% by central banks. What’s more, the fraction that banks are required to hold in reserve is only between 4 and 10% of what they lend.

So national currency exists in three main forms, the second two of which exist only in electronic form:

- Cash – banknotes and coins

- Central bank reserves – held by commercial banks at the central bank

- Commercial bank money – bank deposits created when banks lend money

Only the central bank can create the first two forms of money, and since central bank reserves do not circulate in the economy, what is actually circulating as the public money supply consists of cash and commercial bank money. Of this only the cash is handled visibly. The commercial bank money, which is more then 90% of the total, and which pays for most commercial transactions, only appears in the bank’s account computers.

The Inherent Risk of Money Created by Commercial Banks

As this commercial bank money relies on the system of fractional-reserve banking, it is inherently vulnerable, and can easily destabilize the economy. Put simply, banks are allowed to make long term, illiquid loans, which are risky, and to borrow short term from their depositors, their creditors, on the hopeful assumption that not all the depositors will want to take their money back at the same time.

This is something that they cannot assume, as shown by the repeated bank crashes which have occurred, where the commercial banks have only survived because they have been propped up with money from the central bank and government.

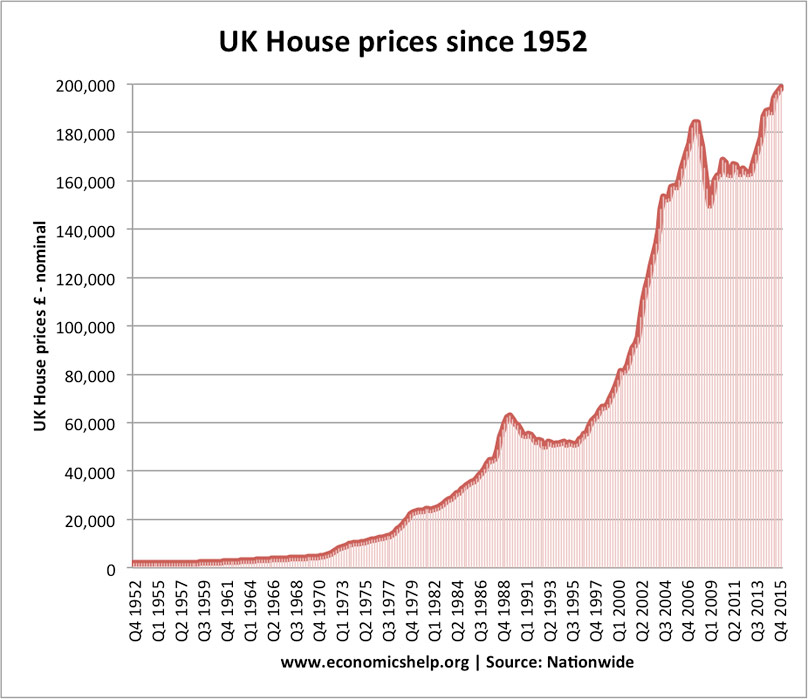

Moreover, as commercial banks make a profit from charging a percentage interest on the money they create by lending, it is in their interest to lend more. For instance, the increase in property prices can be related to the banks’ desire for increased interest receipts from mortgages, and the attendant increase in the supply of money as loans.

Unsurprisingly, there have been many critics of the fractional reserve system who would like to see a situation in which money creation is the responsibility of central banks only – with the proviso that they will not abuse their power to print too much money and cause inflation.

But this is a questionable proviso, for governments are not always trustworthy; they can be corrupt, incompetent, or at the mercy of circumstance, as happened to post-war Germany in the early 1920s, a time of skyrocketing inflation, when prices doubled every two and a half days, and a gold Mark, which had been worth 2.02 paper Marks in 1919, rose to one trillion paper Marks in 1923.

So the statement which began this section, “Money is a kind of IOU which is universally trusted,” turns out to be not true all the time. In the end, the value of this IOU depends on confidence – confidence in the stability of the state, and on the wealth, competence and honesty of the issuer.

What this review shows is that the West has passed from an age of Power, through an age of Faith, to the present age of Money. It is an age which is inherently self-devouring and unstable. Another worldview will replace it, but what it will be is still unclear. For all we see is rapid change, with ever closer links to other cultures.

In the series: Trust, Faith and Confidence–Value and the Role of Money

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

A Comparative Chronology of Money

Roy Davies and Glyn Davies

See a summarized chronology of monetary history from ancient times to the present day.