Current and Future Challenges

Diabetes screening event in India. Photo via World Diabetes Foundation

While countries have managed to decrease deaths from infectious diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as heart disease, stroke, mental illness and injuries are on the rise.

The crisis of displaced populations is likely to increase in the wake of global warming with serious implications for global health, compounded by a critical shortage of health workers. Groups and individuals from all sectors are stepping up with innovative approaches to address these challenges.

Many developing countries must now deal with a “dual burden” of disease: they must continue to prevent and control infectious diseases, while also addressing the health threats from NCDs and environmental health risks. As social and economic conditions in developing countries change and their health systems and surveillance improve, more focus will be needed to address NCDs, mental health, substance abuse disorders, and, especially, injuries (both intentional and unintentional). The UN Sustainable Development Goal #3, Good Health and Well-Being, set a target to reduce pre-mature deaths from NCDs by a third by the year 2030. Some countries are beginning to establish programs to address these issues. For example, Kenya has implemented programs for road traffic safety and violence prevention.

Diabetes, Hypertension, Cancer

Noncommunicable diseases, also known as chronic diseases, tend to be of long duration and are the result of a combination of genetic, physiological, environmental and behavioral factors.

The main types of NCDs are cardiovascular diseases (like heart attacks and stroke), cancers, chronic respiratory diseases (such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma) and diabetes. Musculoskeletal disorders such as osteoarthritis cause disability and decreased quality of life in large numbers as well.

The World Health Organization reports that NCDs disproportionately affect people in low- and middle-income countries where more than three quarters of global NCD deaths – 32 million – occur. Many more millions are disabled. These conditions are often associated with older age groups, but evidence shows that 15 million of all deaths attributed to NCDs occur between the ages of 30 and 69 years. Of these “premature” deaths, over 85% are estimated to occur in low- and middle-income countries. Children, adults and the elderly are all vulnerable to the risk factors contributing to NCDs, whether from unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, exposure to tobacco smoke or the harmful use of alcohol, many of which result from or are made worse by modifiable behaviors. According to WHO:

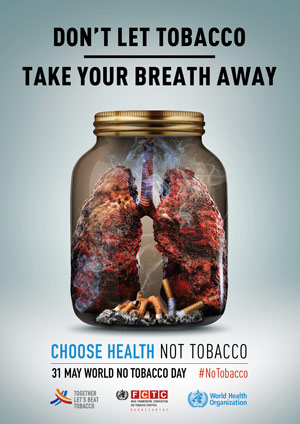

- Tobacco accounts for over 7.2 million deaths every year (including from the effects of exposure to second-hand smoke), and is projected to increase markedly over the coming years.

- 1 million annual deaths have been attributed to excess salt/sodium intake.

- More than half of the 3.3 million annual deaths attributable to alcohol use are from NCDs, including cancer.

- 6 million deaths annually can be attributed to insufficient physical activity.

Recognizing and reducing these risk factors is an important way to control NCDs. Low-cost solutions do exist for governments and other stakeholders. Monitoring progress and trends is crucial for guiding policy and priorities, as is a comprehensive approach involving the collaboration of all sectors, including health, finance, transport, education, agriculture, planning and others.

Investment in better management of NCDs is also critical, including detection, screening and treatment, and providing access to palliative care, all of which can be delivered as primary health care. Evidence shows such interventions are sound investments that when provided early can reduce the need for more expensive treatment.

A decade ago the Afya Njema project began in and around Nairobi, Kenya. The project was a collaboration between the nursing students and their professors from local nursing schools and a US team of nursing students and their preceptors from the University of Massachusetts, Boston. The nurses worked together in special screening clinics to identify patients with elevated blood sugar, high blood pressures and chronic arthritis. Thousands of individuals were screened over the first five years and patients were given information on behavioral changes to help with their newly diagnosed disorders and encouraged to follow up in their community clinics and hospitals.

Since 2013, one of the participating nurse training colleges, P.C.E.A. Tumutumu in Nyeri county has continued those screenings several times a year in communities surrounding their hospital. They encourage patients identified as at risk to seek medical care and address behaviors known to increase cardiac risk, for example smoking, excess alcohol consumption, lack of exercise and obesity.

In 2019, for example, 832 people attended two community screenings. Because of demand, HIV testing was also performed in addition to blood sugars and blood pressure measurements. Children under three years old were dewormed and children under two received vitamin A supplements to reduce potential malnutrition and boost resistance to infection.

Mobile phones can be helpful for patients in preventing and managing NCDs.

Patients served by programs like these are often from poor rural areas where farming is the primary occupation. The majority do not have health insurance or the finances to pay for insulin or the refrigeration necessary to keep insulin in their homes. Community clinics have low cost blood pressure and diabetes medication provided by the government but their supplies are tenuous and not always available.

Mobile phones can be helpful for patients in preventing and managing NCDs. Since 2013, WHO has been working with the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) on a joint initiative, Be He@lthy, Be Mobile. Diabetes was the initiative’s first major program, and in 2014, Senegal launched the first targeted program, mDiabetes, to help people with diabetes manage fasting during the Islamic holy month of Ramadan.

Senegal’s mDiabetes (mobile) program was the first and has now become an annual service with over 100,000 registrations in 2017.

Every morning, mother of six Mariama rises early to sell fish in her local market in Senegal. For more than a decade, she has lived with diabetes and takes insulin regularly. Now her medication is not the only tool she relies on – her mobile phone also plays a critical part. During Ramadan she received daily messages from mDiabetes to help her manage her condition and have the energy needed to work and care for her family, and help her family actively engage in her care. “Every day I would ask my son to check if there was a new message,” Mariama says. “He would help me understand what I needed to do to stay healthy and control my diabetes, and we would then talk about it together.”

The Be He@lthy, Be Mobile initiative created a global handbook to help countries introduce large-scale services. The handbook included content for the SMS messages and support for other areas such as technology, promotion and evaluation. Senegal’s mDiabetes program was the first and has now become an annual service with over 100,000 registrations in 2017. Other countries quickly followed suit. In July 2016, India launched a program that currently supports over 96,000 users. In Egypt, mDiabetes reached over 175,000 people in 2017.

Mental Health Disorders

Mental, neurological, and substance use disorders are common in all regions of the world, affecting every community and age group across all income countries. While 14% of the global burden of disease is attributed to these disorders, most of the people affected – 75% in many low-income countries – do not have access to the treatment they need.

The WHO Mental Health Gap Action Program (mhGAP) aims at scaling up mental health services, especially for low- and middle-income countries. The program asserts that with proper care, psychosocial assistance and medication, tens of millions could be treated for depression, schizophrenia, and epilepsy, prevented from suicide and begin to lead normal lives – even where resources are scarce.

Jan Swasthya Sahyog, (People’s Health Support Group) is a nonprofit community health organization in central Chhattisgarh, India that treats thousands of tribal people each year with support from donors and grants from institutions like the Sir Ratan Tata Trust. Tribal people, India’s indigenous citizens who often lived off the grid and have only recently been pushed into mainstream culture, make up 38% of the population in Chhattisgarh.

A 2015 NPR report, “Why A Snakebite Victim In An Indian Village Won’t Walk Through A Door” covered Manju Thakur, a community health worker with Jan Swasthya Sahyog. Originally from a nearby village, Thakur spoke to a support group of 20 psychiatric patients suffering from bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and depression as well as others who came to work on anger management. Most patients in Bhamni, one of the larger villages in Achanakmar, blame their behavior on the supernatural – a common belief in a culture that widely accepts spirits in both humans and nature.

Thakur tells them the mind is like the body – it needs to be maintained and treated. Thakur says she has to be very convincing and sensitive to steer patients away from traditional healers, who perform rituals or prescribe herbs. She visits homes frequently and shares stories of other people who have recovered in hopes they will consider another type of treatment.

“[The village healer] said there’s a ghost or spirit in me,” says Chotilal Gond, a 30-year-old construction worker who has been hearing voices in his head. Gond had visited the tribal healer before a community worker identified his issue and referred him to the clinic, where Thakur diagnosed him with schizophrenia and convinced him to take the drug olanzapine. Now, he comes to the monthly meetings she holds in the village.

Displaced Populations

According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) we are witnessing the highest level of displacement on record. An unprecedented 70.8 million people have been forced from their homes, with 25.9 million refugees having fled their country – over half of them under the age of 18. There are many causes, from civil war to genocide to natural disasters. The crisis will continue to get worse as the impacts of global warming take an increasing toll. The Red Cross estimates that worldwide, already more refugees flee environmental crises than violent conflict.

The activities of the UNHCR involve providing protection, shelter, advocacy, and health services, and assisting displaced people with rebuilding their lives – especially women, children, minorities, indigenous people, youth, older people, people with disabilities, LGBTI people, and men and boys. The agency also develops a blueprint for planning and action during periods of crisis by preparing in advance for emergencies based on prior experiences and lessons learned.

The work is hard, dangerous and at times overwhelming. The coordination of multiple international agencies is daunting. Each group has their special needs exacerbated by the forced displacement from their homes. This UNHCR report on the reception of migrating Venezuelans in Columbia illustrates both the challenges migrants face and the empathetic spirit that will increasingly be required of people in host countries around the world:

“RIOHACHA, Colombia – Morato Martinez, a 75-year-old Colombian, spends his days painting the walls of Grandpa’s House, the care centre for seniors where he lives in Riohacha. One of his latest murals depicts a couple of grandparents holding hands. It reads: “Grandparents are people full of love.”

“‘This painting had only an abstract meaning until we met the families from Venezuela. Now it has a real meaning,’ Morato says.

“Morato is one of the 18 Colombian seniors who currently live at “La Casa del Abuelo” (Grandpa’s House) in Riohacha, a small city in one of the poorest regions of Colombia, near the border with Venezuela. The home’s daily, quiet routine was altered the day a group of families from Venezuela knocked at the door.

“‘We were witnessing this sudden and massive influx of Venezuelan people: families with children living on the streets and begging for a roof, a soup or for a few pesos,’ explains Maria Peña De Melo, the director of the centre. ‘We decided we had to do something for them as well.’

“Over 4 million Venezuelans have left their home country to date. Over 1.3 million of them have found safety in the neighboring country of Colombia. Some 140,000 Venezuelans arrived in Riohacha in 2018, where they struggle to find shelter and food in an already strained and impoverished region.

“‘In the beginning, the seniors started asking why they would need to make more space for other people,’ Maria says. ‘It’s normal, they are old and they care about their space and privacy. So we started with something simple: on a Sunday, we invited some families for lunch. It went well: the grandparents were willing to host them.’

“At night, the communal area is now full of mattresses where Venezuelan families can sleep, with support from UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency. Along with the 18 usual hosts, 35 Venezuelans sleep at the centre. In addition, around 100 older Colombians and young Venezuelans share a free meal every day.

“‘Many things changed since we started to host the families and their kids’, Maria adds. ‘The seniors see them as members of their families. They feel more “protected,” as they perform some activities together every day. This strengthened the confidence of the abuelitos [grandparents] a lot.’

“Morato used to paint by himself. He is now ready to teach his work to some of the young Venezuelans who live at the centre: ‘As the painting says, grandparents are people full of love: we want this place to be more beautiful and livable. We can teach young people arts, while we can learn from them how to smile again.’”

Older Columbians and Venezuelans take care of each other under the same roof

UNHCR.org

Future Challenges

As the identification of global health issues and public awareness and demand for treatment and services increase, it will be important to consider best practices and avoid recreating processes that we know are insufficient, costly and, most importantly, not effective or even counter productive – for example, using antibiotics for viral infections or being passive to vaccination opportunities.

Technology and entrepreneurship too must be brought to bear in the right way. In developed countries, we are accustomed to technology that requires service and goes quickly out of date, but this approach can hinder delivery of basic health care in the world’s poorest countries. Many a high tech lab has been set up in rural areas in Africa and India, for example, only to lie dormant when equipment fails and there is no expertise or money to fix them. Some very practical products may take into consideration the special circumstances involved in delivering health care in developing countries, such as an inhaled measles vaccine that is easier to transport and administer and requires no refrigeration. But getting these products to market and into general circulation requires manufacturers to buy in to the cost effectiveness of production and marketing. If they are not convinced of profitability – for example, they already manufacture the injectable measles vaccine – then the product will not make it to market.

Global Workforce Shortage in Healthcare

The greatest immediate challenge may well be the growing shortfall in the healthcare workforce, projected by WHO to be a dearth of 18 million workers by 2030. Though affecting all countries, as usual the hardest hit will be the poorest. The actual causes of health worker shortages and effective strategies to resolve the issue are still being examined. Data on foreign-born and/or foreign-trained health workers provide evidence of increasing international migration and mobility, as well as increasing complexity in patterns of movement. In Uganda, 40% of the healthcare workforce is foreign-trained, foreign-born. In South Africa the largest group is from the United Kingdom. Other countries complain of a brain drain of health professionals once they are educated locally.

Two of the most promising ways to help mitigate this coming crisis are increased support for community health workers and the informed application of true work savers and assistants in health technologies.

Community Health Workers

Traditionally, trained volunteers who live in their rural communities play an essential role in promoting such activities as vaccination and birthing assistance from pre-natal care to increasing infant survival. Health ministries are responsible for recruiting and training, and efforts to standardize and support the workers, including paying a stipend for their work, are evolving.

In March 2019, WHO promoted the role of community health workers for delivering primary health care, defining the opportunity and challenges: “Community health workers should not be regarded as a way to save costs or as substitutes for health care professionals, but as an element of integrated primary health care teams. The role of community health workers should be defined and supported with the overarching objective of constantly improving equity, quality of care and patient safety. There is increasing recognition of the potential of the health sector to create qualified employment opportunities, in particular for women and youth, thus contributing to the job creation, economic development and gender equality agendas that many countries aim to address.”

Last Mile Health, an organization, founded in 2007 by survivors of Liberia’s civil war and American health workers who share a commitment to health equity and social justice, is also focused on promoting the role of community health workers. Its Community Health Academy provides free training for both workers and the health ministry officials who design, lead and manage in-country programs. Currently Rwanda, Ethiopia, Brazil, Bangladesh have developed effective programs now being offered as case studies.

Promising Health Technologies

Last Mile Health promotes equipping workers with mobile phone technology to help them register, refer and diagnose patients. Drones have also received considerable excitement and press as the future workhorse in low resource countries that characteristically have poor transportation infrastructure and many small isolated villages. Distance and weight limitations have made the successful jobs they perform relatively small in scope, such as mapping or photographing areas after a disaster or determine where fleeing populations have regrouped. Unmanned helicopters and aircraft are also being tested to deliver small cargo boxes for relief work. Another limiting feature of these unmanned technologies is that they have moving parts that require expert maintenance and are expensive, making availability dependent on sizable grants and donations.

Encouraging Entrepreneurial Development

There are a number of initiatives to promote technological advancement appropriate for low and under resourced countries that have developed in the past decade. MIT’s Solve is an initiative that provides tech entrepreneurs with funding and access to expertise and networks that can carry the products to a new level of development. Working on different themes, the 2018 challenge produced 33 finalists who were attacking the need for quality data and equipment designed by and for health workers in low or under resourced areas. For example, one group developed a rechargeable silicone band to wrap around a newborns head and continuously measure four vital signs: pulse, respiratory rate, blood oxygen saturation and temperature. The band is designed to resist extreme heat and exposure to dust or other elements. The data collected can be sent to a dashboard where nurses would be alerted of any changes in the babies vital signs.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s Grand Challenge awards grants to solve or brainstorm problems they and others in the global field have identified as priorities. The world’s greatest minds and laboratories have the opportunity to obtain support for their research. Successful applications are then given funding to pursue. But a good idea, like the inhaled measles vaccine, may go nowhere if not picked up by a commercial manufacturer, and many projects languish. In 2014, The Seattle Times reported that “despite an investment of $1 billion, none of the projects funded under the Gates Foundation’s “Grand Challenges” banner has yet made a significant contribution to saving lives and improving health in the developing world.” Critics of the program cited the emphasis on technological fixes, rather than on the social and political roots of poverty and disease. “The main harm is in the opportunity cost,” said public health expert Dr. David McCoy. “It’s in looking constantly for new solutions, rather than tackling the barriers to existing solutions.” The toll of many diseases, critics say, could be lowered simply by strengthening health systems in developing countries.

The Oxfam report to the 2019 World Economic Form, Public Good or Private Wealth, makes an even sharper point: “In most countries – both developed and developing – having money is a passport to better health and a longer life, while being poor all too often means more sickness and an earlier grave. … Each year, many die or suffer unnecessarily because they cannot afford healthcare, and 100 million people are forced into extreme poverty by healthcare costs. It doesn’t have to be this way. Inequality is not inevitable. There is no law of economics that says the richest should grow ever richer while people in poverty die for lack of medicine. …To succeed, countries need to scale up the public delivery of services. When publicly delivered services are made to work, the scale and speed of their impact on poverty reduction cannot be matched.”

External Stories and Videos

The Chronic Stress of Being Black in the U.S. Makes People More Vulnerable to COVID-19 and Other Diseases

April Thames, Yes! Magazine (Reprinted with permission from The Conversation)

Racism is a chronic, uncontrollable, and unpredictable stress that can wreak havoc on the mind and body.

Could unemployed youth solve the health care worker crisis?

Gabriella Jóźwiak, Devex

According to the World Health Organization, 40 million new health and social care jobs must be created globally by 2030 to meet Sustainable Development Goal 3 of universal health coverage. At the same time, global youth unemployment reached 71 million in 2016, according to International Labour Organization data. Could the two problems be used to solve each other?

How Big Business Got Brazil Hooked on Junk Food

Andrew Jacobs & Matt Richtel, New York Times

As growth slows in wealthy countries, Western food companies are aggressively expanding in developing nations, contributing to obesity and health problems.