The Iberian Peninsula–Al-Andalus (750–1031)

The confluence of cultures, religions and brilliant minds that came together in Islamic Spain created a civilization that changed human history. As S.P. Scott writes in History of the Moorish Empire in Europe, during that splendid period, “ignorance was regarded as so disgraceful that those without education concealed the fact as far as possible, just as they would have hidden the commission of a crime.”

“In Al-Andalus, for eight centuries, communities of Muslims, Jews, and Christians lived side by side or intermingled the one with the other. There was no precedent for so extended an experiment in the history of Europe, and it has not been equaled since, for daring, brilliance, or productivity.” (Steven Nightingale, Granada: A Pomegranate in the Hand of God, p. 119)

As previously mentioned, in 750 the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyad dynasty in a deadly feud that left the latter facing near extermination. Luckily, 16-year-old Abd ar-Rahman escaped and, with the help of those still loyal to the Umayyads, fled to Spain, where he had Berber relatives on his mother’s side. With loyal Umayyad help, he entered Cordoba (formerly Khordoba of the Visigoths) and became its ruler.

Having secured a power base, Abd ar-Rahman I proclaimed himself the first Umayyad ruler of Andalusia and refused to recognize the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad. However, it was not until the early ninth century, at about the same time as Al-Mamun started his House of Wisdom, that Abd ar-Rahman’s great-grandson, Abd ar-Rahman II, set about creating a center of learning to rival Baghdad.

Under Abd ar-Rahman and his descendants, Cordoba became known as the “Ornament of the World,” the capital of Al-Andalus – or Andalusia, as it is known today. For about a century beginning in 900, Al-Andalus became the most heavily populated area of Europe. Arabic philosophers, trained in the East, migrated there, and schools and libraries flourished. From 912 to 961, Caliph Abd ar-Rahman III reigned as Emir of Cordoba and then as its caliph. His son, al-Hakam, built a massive palace-library complex, the Madinat al-Zahra, near Cordoba, housing half a million books. Hasdai Shaprut, the Jewish polymath, was a prominent advisor, physician and emissary of the caliph, and traveled to Leon to treat the Christian king Sancho. Sephardic Jews engaged in explorations of philosophy and science, and created monumental legal codes and a revolution in poetry. One of the most prominent among them was Samuel ibn Nagrella (993–1056) a medieval Spanish Talmudic scholar, grammarian, philologist, soldier, merchant, politician and influential poet.

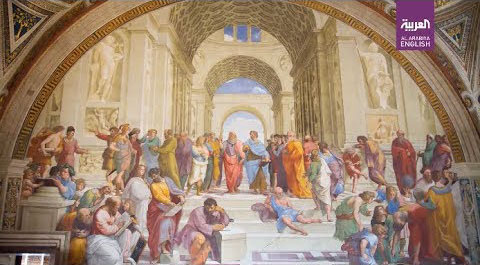

This convivencia of cultures, religions, languages and brilliant minds changed the course of European history. To quote Steven Nightingale again: “It was a culture of preternatural brilliance, with its doctors and astronomers, poets and viziers, scholars, translators, poets, mystics, and mathematicians. … By their work, these men shared the best of the science and philosophy present in one of the most advanced cultures in the history of the Mediterranean: a recent evaluation among historians places Al-Andalus at its zenith no fewer than four centuries ahead of Latin Europe. The texts they translated are a crucial part of the foundation of the Renaissance. It is impossible to imagine the rapid development of the West in science, culture, and commerce without just this gift of knowledge.”

Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (936–1013; Latin name Abdulcasis)

Tremendous achievements in medicine were made in Andalusia. Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (Abulcasis) known and The Father of Medicine was the inventor of more than a hundred medical instruments, including the forceps, surgical hook, bone-saw, speculum and syringe. Together with al-Razi’s Al-Hawi and Avicenna’s Canon, al-Zahrawi’s Kitab al-Tasrif (The Method of Medicine) was one of the main reference books on medicine in Europe during the Middle Ages. In this book al-Zahrawi lists many procedures that he developed, such as a surgical procedure to relieve migraines, and a method to fix a dislocated shoulder, both of which were picked up and developed further by later physicians.

Astronomical achievements in Andalusia included the work of al-Zarqali, who made the first universal astrolabe that could be used anywhere in the world, and who figured out that the orbit of Mercury is oval rather than circular (although he wrongly thought that Mercury orbited the Earth). He is one of only two astronomers named in Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres.)

Abu l-Walid Muhammad ibn Amad ibn Rushd (1126–1198; Latin name Averroes)

Ibn Rushd the muslim philosopher who paved the way to the European. [Al Arabiya is funded in whole or in part by the Saudi government.]

Averroes was a polymath and one of the world’s most important philosophers; he argued that religion and philosophy are not incompatible but, on the contrary, work together. “Truth does not contradict truth,” he said. Averroes wrote commentaries on all of Aristotle’s works, as well as a translation of, and commentary on, Plato’s Republic. Averroes’ many books were studied in Europe and initiated an intellectual revolution in philosophy, education and theology. Just a few years after his death, the great universities in Paris and Oxford began operation. They were secular and included subjects such as logic, metaphysics, ethics and the natural sciences. Students might go on to study medicine, law or theology, but each of those disciplines had their foundation in philosophy, thanks in part to Averroes.

“Ignorance leads to fear, fear leads to hatred, and hatred leads to violence. This is the equation.” (Averroes)

Solomon ibn Gabirol (1028–1058; Latin name Avicebron)

Avicebron was a Jewish philosopher and poet. Among his many works was Fount of Life (Fons Vitæ), a long treatise based upon Sufi illuministic philosophy. Avicebron wrote both sacred and secular poems in Hebrew, the most famous of which was Keter Malchuth (Royal Crown). “Ibn Gabirol, the Jewish follower of the Arab Sufi, exercised an immense and widely recognized influence upon Western thought. … Because he wrote in Arabic, many authoritative Christians of the northern European school, then imbibing ‘Arab’ learning, thought that he was an Arab. Some at least considered that he was a Christian, ‘sound in doctrine,’ and they said so. The Franciscans accepted his teachings, which they eagerly transmitted into the Christian stream of thought, having culled them from a Latin translation made about a century after Avicebron’s death.” (Idries Shah, The Sufis)

In his Fons Vitae, Avicebron asks ‘Quare factus est homo? (Why was man made?). He maintains that the goal is to understand the ends or purpose of the human being. A human ought to “pursue knowledge of his final cause [or purpose] according to which he was composed,” (Fons Vitae 1.2, p. 4, lines 8–9)

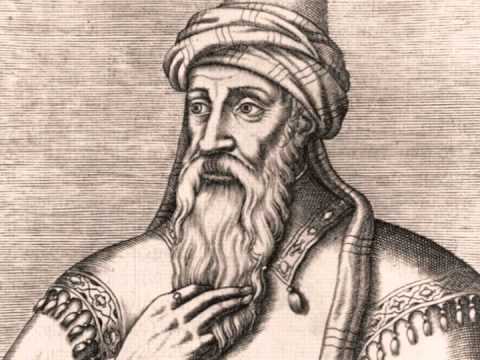

Abu Imran Musa ibn Ubaid Allah ibn Maimun (1135–1204; also known as Moses Maimonides)

“MAIMONIDES” BBC Interviewer Melvyn Bragg is joined by John Haldane, Professor of Philosophy of University St. Andrews, Sarah Stroumsa the Alice and Jack Ormut Professor Emerita of Arabic Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the first woman to serve as Rector of the Hebrew University, and Peter Adamson, Professor of Ancient and Medieval Philosophy, Kings College, London.

Moses Maimonides was a physician and philosopher and is generally regarded as the greatest Jewish thinker of the Middle Ages. By the time of his ninth birthday, the Berber Almohads of North Africa invaded the Iberian Peninsula, bringing with them a more aggressive form of Islam. Their slogan was “No synagogue, no church.” Upon the invasion of Al-Andalus, young Maimonides and his family fled from Cordoba to Fez in Morocco and finally ended up in Cairo, then a center of learning. Maimonides eventually became known as the city’s leading physician, a clinician whose skills were sought from far and wide. Despite long days spent caring for patients, Maimonides wrote extensively about both medicine and philosophy. His medical works span all topics of clinical medicine and reflect rational thinking and an understanding of the relationship between mind and body. Well known for his philosophical writings, Maimonides tried to present two separate tracks – one for the nation and the other for the individual. Asking how it would be possible to build a righteous nation, he compiled the Mishneh Torah, a code of religious law. But there might be other ways the individual can take towards perfection, he claimed, noting both Moses and Aristotle as examples. In his masterful philosophical work, The Guide for the Perplexed, Maimonides addresses the question of how one can reconcile what science teaches with what religion teaches. He asserted that a lot of scripture is allegorical or metaphorical and refers to the inner truth that God is beyond any science, holding that there is a single God one cannot perceive and can only get close to by understanding what He is not; one cannot say or think anything about God, since nothing is on a par with Him.

“What Maimonides is doing all the time is emphasizing the transcendence of God as the ground of Being, the ground of Knowledge, God’s knowledge is the same as Reality. … What we are to do; how we are to perfect ourselves? We are made as images of God, we have intellect, we have will, we are to engage in this imitation of the divine by becoming to the extent that we can godlike, by transforming the world that God has expressed out of his nature back in to mind through our knowledge of it. … So the world is a creation out of mind and is a reception into mind. … We come to perfection in understanding the reality that surrounds us.” (John Haldane, Professor of Philosophy of University St. Andrews)

Maimonides influenced the Italian Thomas Aquinas (c.1225–1274) and to this day is considered the topmost Jewish thinker.

In the series: The Journey of Classical Greek Culture to the West

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

Watch: Science & Islam

BBC full series with Jim Al-Khalili

The history of Islamic science and it’s subsequent spread through Europe.