Judaism

The Axial-Age Prophets

Axial-Age prophets no longer saw Yahweh as a god of war, or one appeased by empty ritual, they emphasized a more individual relationship with Yahweh that involved individual responsibility, morality and justice.

The early 8th century BCE was a more peaceful time with both states expanding and trade flowing freely between them. The practice of religion was now completely external and superficial, the regular performance of ritualistic obligations and sacrifices the only requirement. Over this period, the rich became extremely so and their good fortune was interpreted as evidence that the divine Yahweh rewards materially those who regularly perform the prescribed ritual obligations.

The poor, they claimed, were so because they did not do so and thus they deserved their lot. In reality the poor were exploited by the rich and a corrupt political and legal system made it impossible for them to achieve a better life.

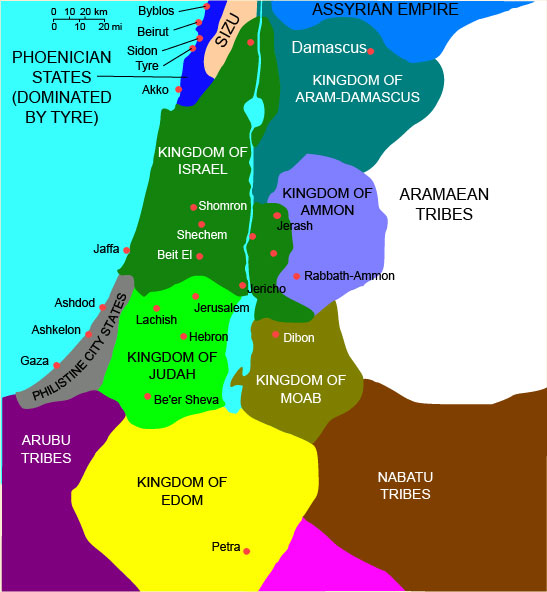

Into this situation entered the prophet Amos, a common man who came from Tekoa not many miles from the city of Jerusalem. Amos made his living raising sheep and sycamore trees and selling them in the market towns and villages of the northern kingdom of Israel. He became deeply troubled by the disparity he saw between the rich and poor, and by the way in which political and religious leaders tried to justify it.

Dreams and visions convinced Amos that Israel would collapse as a consequence of its behavior. He saw that Yahweh was not impressed by empty ritual and festivals, but instead wanted justice to “flow like water and integrity like an unfailing stream.” He felt that Yahweh would destroy Israel, its king and the lands surrounding Israel. And Israel would suffer the most because the Israelites knew God.

Attributing the power of any god beyond its normal territory was an unusual idea at the time. But to Amos, Yahweh was the only god, and not subject to the boundaries of any country, He is the God of all, and His demands are universal and affect all nations.

The prophet Hosea was active 753–725 BCE, just a few years later, but by this time Israel’s monarchy was unstable and invasion by Assyrian armies seemed, and was, imminent, only kept at bay by enormous tariffs paid resentfully by the people. Like Amos, Hosea was certain that Yahweh cares nothing at all for ritual services, but for Hosea Yahweh is primarily a God of Love. His power and justice, though essential, are subordinate to His love and mercy. He desires correct understanding and morality from the people who are “destroyed from lack of knowledge.”

To Hosea, Yahweh’s punishments are remedial, not retribution, and as such they are an expression of His love, and used as a last resort to teach lessons that people refuse to learn in any other way. He warns that the people of Israel will be captured, but in captivity will be an opportunity for them to gain a better understanding of Yahweh and how to worship him. From this point on it seems that the Hebrew people understood that Yahweh would never leave them, and that any suffering, tragedy or hardship they encountered was an opportunity for learning.

Hosea’s words imply an individual relationship with Yahweh and a responsibility of the self which is Axial in thinking: “Who is wise, and he shall understand these things? Prudent, and he shall know them? For the ways of the Lord are right, and the just shall walk in them: but the transgressors shall fall therein” (Hosea 14:9). Both saints and sinners must learn that “it is time to seek the Lord” (10:12).

Isaiah was active in Jerusalem in the Southern Kingdom of Judah in the 740s and prophesied for at least 40 years. Although privileged himself, he was, like Amos, an outspoken voice for the common people who were being victimized by the rampant corruption of the ruling class. Like Hosea, Isaiah did not predict the final or complete destruction of the nation as did Amos, but instead saw the Assyrian invasion that conquered Israel in 722 BCE as an inevitable punishment from Yahweh, that would result in a change in the moral leadership of Israel and in an increase in his people’s

spiritual strength.

The prophecies of Isaiah clearly express Israel’s messianic hope for the first time. The term Messiah means “anointed one,” or one who has been chosen by Yahweh for a specific purpose. In Isaiah’s prophecies, the Messiah is portrayed as an ideal king and judge who will understand the plight of the poor and will ensure that their rights are protected and that they are justly treated. The concept of a coming Messiah took on a number of different meanings during the centuries that followed and became one of the most important ideas of Judaism.

In the series: Judaism

Related articles:

- Axial Age Thought

- Hinduism

- Buddhism

- Zoroaster

- Greece: The European Axial Age

- The Peloponnesian War 431BC – 404BC

- Religious Life in the Greek Axial Age

- Religious Life in the Greek Axial Age (Part 2): The Mystery Cults

- The Panhellenic Games

- The Theater of Ancient Greece

- The Pre-Socratic Philosophers

- Socrates (470–399 BCE)

- Aristotle (384–322 BCE)

- China

- The Spring and Autumn Period (770–476 BCE)

- The Hundred Schools of Thought