Algorithmic Gatekeepers

Once humans alone brokered information. But now layers of online algorithms intermediate our access to the digital information ecosystem. What happens when social media algorithms become the prime gatekeepers?

Instead of being the central points from which news is broadcast directly to the public, the news media are now part of a much larger information ecosystem. They broadcast to the public on their websites, on their Facebook pages, and via their Twitter feeds, and YouTube channels. The direct consumers following these channels, in turn, repost them through twitter and Facebook, where they reach further audiences.

Philip Napoli, in his book Social Media and the Public Interest, refers to algorithmic gatekeeping to describe the growing influence of algorithms on the selection of news that reaches us. The major newspapers, like the New York Times and the Washington Post, use their own algorithms to analyse story content and combine this with measures of how well the stories perform on Facebook, to decide which future stories to recommend on their Facebook pages. As Napoli points out, this creates a multi-step process by which news is disseminated to the public. The New York Times, for example, still uses human editors to decide what stories to publish each day in total. But its recommendation algorithms will select only a subset of these stories to post to Facebook and Twitter, based on which ones will perform best on social media. Those who follow the Facebook pages or Twitter feeds published by the Times will have their selection of stories further curated by social media algorithms that take into account the personal characteristics of these users. They in turn will share stories to their followers and again social media algorithms curate stories for each follower.

Mainstream news editors will apply a number of criteria to decide what is newsworthy, but they boil down to whether the story has societal significance. What criteria do Facebook’s algorithms use? The media scientist, Michael Ann DeVito analysed Facebook newsroom and Notes blogs, as well as patent filings, and securities and exchange commission filings to determine which values the algorithms follow in selecting stories for your news feed. For Facebook they boil down to personal significance. Your friend relationships are the single biggest decider of what stories you see.

Hacking the Information Ecosystem

What happens when the social media algorithms become the gatekeepers of our information ecosystem? In her talk, the internet’s original sin, Renée DiResta observes that the information ecosystem that was built for advertisers is also remarkably effective for propagandists. The recommendation algorithms prioritize what is popular and engaging over what is true. The original intent of the social media applications was for the public to provide content that was personal, authentic, and of interest to friends and followers. Famous people and “influencers” were more than welcome to join in. The personal, the authentic, and the famous would keep people’s attention on their phones and screens so that they could continue seeing ads.

But it is not only the advertisers who want the public’s attention. Governments and terrorist organizations, domestic ideologues and true believers also want our attention. These actors spend millions of dollars and thousands of hours of online work attempting to sway public opinion with propaganda that is meant to look like it is coming from regular citizens. The media scholars Jonathan Corpus Ong and Jason Vincent Cabanas studied how political parties do this in the Philippines. At the top level, politicians (or hyperpartisan organizations) hire public relations (PR) firms as their experts in this domain. At the next level, the PR firms pay digital influencers, celebrities, and pundits to carry the message. These influencers have tens of thousands to millions of followers. The PR firms also hire (and pay very poorly) thousands of middle-class workers to re-post the messages using multiple fake accounts to create the illusion of widespread engagement. The followers of these parties within the public join in and further amplify their propaganda.

The TOW Center for Digital Journalism identified 450 websites in the US that are masquerading as local news organizations. With folksy names like the Ann Arbor Times, Hickory Sun, and Grand Canyon Times these sites produce partisan political content in amongst articles on real estate prices and best places to get gas. Most of the content is generated automatically, not by local writers. The content eventually appears on Facebook and Twitter news feeds.

Free Speech

For a long time neither the technology companies nor legislators wanted to touch this problem, which had been brewing for years. It was only after Russia’s massive attack on the 2016 US election that the elected officials and social media companies began to take notice. One of the central metaphors for protecting free speech is that of the marketplace of ideas. In a well-functioning marketplace good products and services outperform bad ones. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes famously said: “The ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas—that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.” Justice Louis Brandeis, in his concurring opinion on Whitney v. California wrote: “If there be time to expose through discussion, the falsehoods and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.” This opinion was directly concerned with the democratic process, whereby citizens had the right—and the duty—to participate in the discussion of ideas even in opposition to the government. It is through the competition within the marketplace of ideas that we can distinguish the true from the false.

The media scholars such as Philip Napoli, Whitney Philips, Renée DiResta, Zeynep Tufekci, and many others are telling us that that our information ecosystem shows clear signs of market failure, both in ideas and in information. False stories, conspiracy theories, and misinformation outnumber and outperform true stories. As we will explore next, it is not just the platforms that are the problem. Our own minds play a major role in this.

In the series: Social Networks

Further Reading »

Websites:

Data & Society

Data & Society studies the social implications of data-centric technologies & automation. It has a wealth of information and articles on social media and other important topics of the digital age.

Stanford Internet Observatory

The Stanford Internet Observatory is a cross-disciplinary program of research, teaching and policy engagement for the study of abuse in current information technologies, with a focus on social media.

Profiles:

Sinan Aral

Sinan Aral is the David Austin Professor of Management, IT, Marketing and Data Science at MIT, Director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy (IDE) and a founding partner at Manifest Capital. He has done extensive research on the social and economic impacts of the digital economy, artificial intelligence, machine learning, natural language processing, social technologies like digital social networks.

Renée DirResta

Renée DiResta is the technical research manager at Stanford Internet Observatory, a cross-disciplinary program of research, teaching and policy engagement for the study of abuse in current information technologies. Renee investigates the spread of malign narratives across social networks and assists policymakers in devising responses to the problem. Renee has studied influence operations and computational propaganda in the context of pseudoscience conspiracies, terrorist activity, and state-sponsored information warfare, and has advised Congress, the State Department, and other academic, civil society, and business organizations on the topic. At the behest of SSCI, she led one of the two research teams that produced comprehensive assessments of the Internet Research Agency’s and GRU’s influence operations targeting the U.S. from 2014-2018.

YouTube talks:

The Internet’s Original Sin

Renee DiResta walks shows how the business models of the internet companies led to platforms that were designed for propaganda

Articles:

Computational Propaganda

“Computational Propaganda: If You Make It Trend, You Make It True”

The Yale Review

Claire Wardle

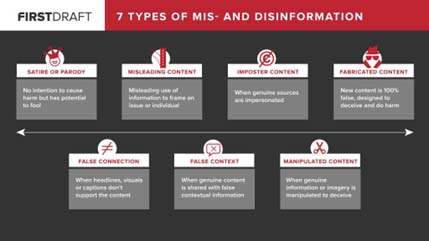

Dr. Claire Wardle is the co-founder and leader of First Draft, the world’s foremost non-profit focused on research and practice to address mis- and disinformation.

Zeynep Tufekci

Zeynep is an associate professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill at the School of Information and Library Science, a contributing opinion writer at the New York Times, and a faculty associate at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University. Her first book, Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest provided a firsthand account of modern protest fueled by social movements on the internet.

She writes regularly for the The New York Times and The New Yorker

TED Talk:

WATCH: We’re building a dystopia just to make people click on ads

External Stories and Videos

Watch: Renée DiResta: How to Beat Bad Information

Stanford University School of Engineering

Renée DiResta is research manager at the Stanford Internet Observatory, a multi-disciplinary center that focuses on abuses of information technology, particularly social media. She’s an expert in the role technology platforms and their “curatorial” algorithms play in the rise and spread of misinformation and disinformation.