Greece:

The Theater of Ancient Greece

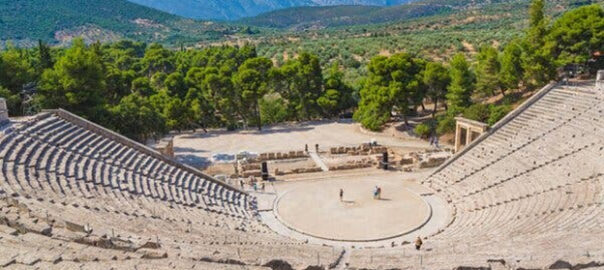

Greek dramatic plays, held in honor of selected gods, were unlike anything the world had seen before. They were performed in amphitheaters that provided a physical space in which foundational elements for the growth and sustainability of democracy were nurtured.

Over at least three days Athenians had the opportunity, time and space to experience and think about those aspects of humanity that threatened the wellbeing and eunomia (balance) of their society, both in the oikos (family) and in the polis (state.)

By the end of the sixth century, Athens had become the home of a tradition of drama that strengthened the bonds of the entire community. The most splendid of the Bacchic festivals, the City Dionysia, took place in March each year to welcome the spring. It was held from the first within the precincts of the city, in the sacred enclosure of Eleuthereus on the southeastern slope of the Acropolis, where the remains of the great Athenian theater are still to be seen.

As part of the sacred grounds, the theater was already otherworldly. Peter Meineck, Professor of Classics in the Modern World at New York University, describes it as “a sacred space where liminal transgressions could occur.” For the Greeks, the act of watching or performing was a sacred duty. Greek theaters were all open-air and had similar layouts to the one at the Sanctuary of Dionysus Eleuthereus, allowing audiences to overlook the city, the countryside and ocean; and encapsulating the entire sky, which was, in fact, the most prominent feature in the visual field of the spectator. The Greek terms for sky—ouramus, Olympus, and ether—were interchangeable with the word for heaven or the place where the gods resided.

In his book Theatrocracy: Greek Drama, Cognition, and the imperative for Theatre, Meineck points out that “Just as sky-space forms the realm of contemplative truth for Plato and is the place where the true forms reside, so in the Greek theatre the sky served a similar cognitive function by creating a sense of spatial dissociation that can contribute to the altering of mental states and promotes feelings of spirituality and of the divine.”

Referring to the work of the neuroscientist Fred Previc, Meineck noted that prioritizing the outward and upward far-distance in everyone’s field of vision would have stimulated a dopamine reaction whereby all those present—some strangers, some erstwhile enemies—would have experienced euphoria and a sense of oneness. Unlike our modern theaters, he says, in those of ancient Greece, “there was no division between the inside and the outside; the world and the play were deliberately visually, aurally, and olfactorily blurred, as was time and place, myth and reality, the world of humans and the realm of the divine.” The sense of unity and selflessness inspired by this experience would have been extremely important to the fledgling democracy of the Greeks.

The plays took place in a stadium that seated about 20,000 people and were held on three specific and consecutive days each year, from sun up to sun down.

Each day one poet alone would present a trilogy, followed by a burlesque satyr play, which was shorter and often connected thematically to the plays that preceded it. In the Greek agonistic spirit (from the Greek agōnistikos, from the word agōn meaning contest), these plays were part of a competition between three tragedians selected for the event by the Archon responsible for organizing it all. In addition, more frequently than not, the main characters in every play were in conflict with each other.

Tragoidia is a formal term that refers not to the subject matter but to the form, and its meaning was more like our word “play” than our word “tragedy.” According to Aristotle, the plot of a Tragoidia needed to be serious. Nevertheless, those that survived are almost all tragedies in our sense of the word.

Actors were generic figures: they wore masks, their robes were indistinguishable from each other, their movements ritualized. To move the audience, they relied entirely on the quality of their voices, dance-like movements, and on the poetry they spoke and sang. Sophocles, for example, avoided performing in his plays because his voice was too weak.

The plots were almost always drawn from traditional Greek mythology and tended to focus on conflict within a great family from the remote and heroic past. So the broad outline of the story and the main characters would be known to the audience. But the play’s details were modified, and minor characters often invented in order to refocus the story to highlight whatever angles the writer wanted, putting whatever words he wanted into the character’s mouths. Thus, the tragedy commented on wider contemporary social themes, like justice, the tension between public and private duty, the dangers of political power, and the balance of power between the sexes.

Aspects, perspectives and the relevance of the trilogies would be discussed by citizens, since tragedy not only validated traditional values, reinforcing group cohesion, but also exposed weaknesses, conflicts and doubts in both the individual and the state. Athenian democracy was new and the transition from traditional blood or tribal loyalty to loyalty to the state, although intellectually welcomed, would likely have been more difficult for individuals to internalize. Athenians applied what they learned in the theater to other aspects of their lives, to difficult civic issues, to their deliberations in the Assembly and to their judgments in the courts.

The plays told stories that dealt ruthlessly and relentlessly with human passions, conflicts and suffering, while at the same time expressing Greek ideals. They were open to all citizens, though women and slaves were almost certainly excluded. Over at least three days, Athenians had the opportunity and space to experience and think about those aspects of humanity that threatened the wellbeing and eunomia (balance) of their society, both in the oikos (family) and in the polis (state.)

Here in open-air theaters the public could watch as every transgression—even the most horrific of human drives and passions—was acted out and released in a very controlled setting. It provided a cathartic experience (or cleansing) for everyone; here suffering was experienced and accepted, and empathy fostered. Greek Classical Theatre was a safety valve for the society where every year, passions and concerns were revealed and then could be controlled.

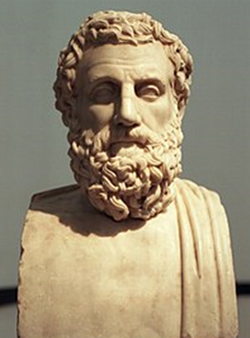

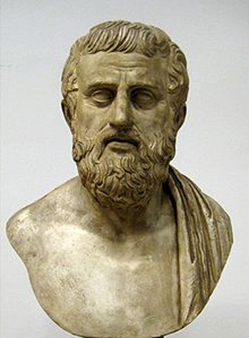

Karen Armstrong writes in The Great Transformation, “Tragedy taught the Athenians to project themselves toward the ‘other’ and to include within their sympathies those whose assumptions differed markedly from their own. … Above all, tragedy put suffering on stage. It did not allow the audience to forget that life was ‘dukkha,’ painful, unsatisfactory, and awry. By placing a tortured individual in front of the polis, analyzing that person’s pain, and helping the audience to empathize with him or her, the fifth-century tragedians—Aeschylus (ca 525–456), Sophocles (ca 496–405), and Euripides (ca 484–406)—had arrived at the heart of Axial Age spirituality. The Greeks firmly believed that the sharing of grief and tears created a valuable bond between people. Enemies discovered their common humanity …”

Storytellers had always told versions of well-known myths, tailored to isolate and address societal problems, but now, for the first time, the words were played out by human representatives, rather than just narrated. These ceremonies were religious, they included libations to the gods, music and dancing with stories now acted out by masked actors. A goal was for everyone present to achieve a receptive state – one that is “outside oneself” the Greek meaning of “ecstatic” – in which the actors, chorus and audience could participate “as one”.

Plays posed questions, revealed problems, exposed human weaknesses and strengths, and provided a cathartic experience for everyone present, one that helped to facilitate transformation and change at all levels of society, whether personal or political. Thus, theater became a driving force designed to keep Democracy on track.

Greek religion in its developed form lasted more than a thousand years, from the time of Homer (thought to be 9th or 8th century BCE) to the reign of the Roman emperor Julian (4th century CE). During that period its influence spread as far west as Spain, east to the Indus River, and throughout the Mediterranean world. The Romans identified their deities with those of the Greeks; the stories and images of Christian saints and heroes echo the actions, values and images of the heroes and deities of the ancient Greek world.

The Mask in Greek Theater

Performers of Greek theater in the fifth century BCE were always masked. To us this seems strange—why were masks so crucial to ancient drama? What did the mask do?

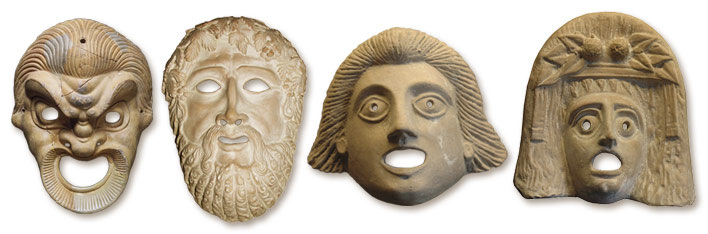

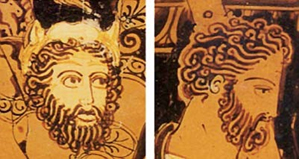

Unfortunately, there are no masks from this period when the great plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides were first performed. But representations of masks on art forms such as vase paintings or sculptures clearly show that masks then were unlike the more typical mask we know today, with its gaping mouth and stony face.

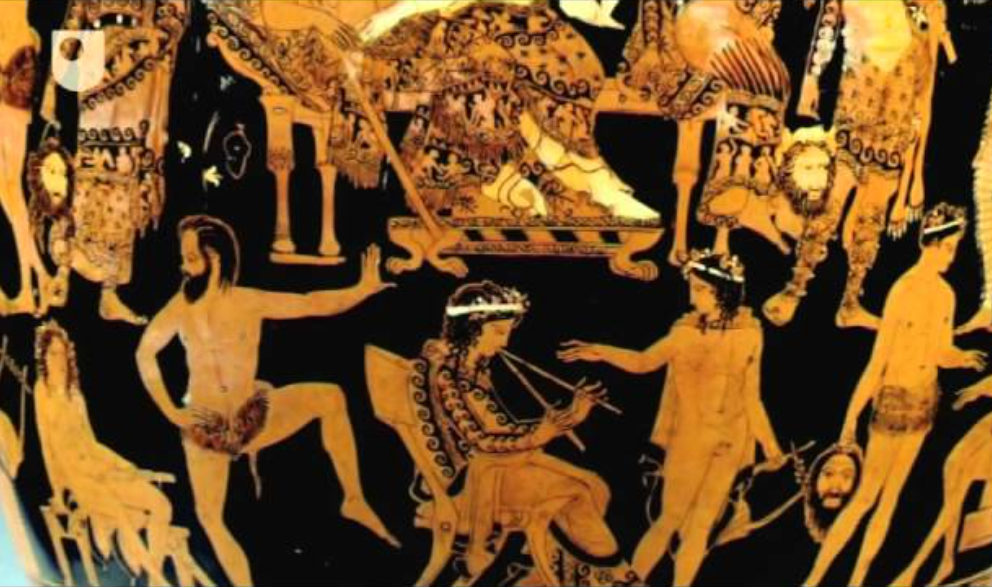

In his article “The Neuroscience of the Tragic Mask,” Professor Meineck tells us that a 5th-century mask was most likely made of linen or leather. It had normal eyes painted on it with holes representing the iris through which the actor could look. The mouth was relatively small but enabled the actor to speak through it. There was no sign of any device that might help the voice project or to ensure its quality. The mask was attached to the head by a hood, or “sakkos” that had real hair attached to it and, if male, on the face as well. According to Meineck, this “gave the mask a sense of life and movement.” Among the possible mask images which the professor selects as representative is the mask of Herakles as seen on the Pronomos Vase of the 5th century.

When a masked person enters the stage, we know that something is about to happen. Any mask has a compelling quality of stillness that holds one’s attention longer than would looking directly at a human face, which, in any case, elicits a very strong (if not the strongest) visual response in us. As we said, all the actors were masked, so 15 to 50 people would enact a drama based on a foundation of extraordinary myths with which audiences were already familiar, but which exposed anew the heights and depths of human nature, frequently evoking contemporary conflicts and concerns.

The mask draws our attention and our emotions to it—its deliberate ambiguity compels us to stay watching. Just as the viewer of the Mona Lisa is compelled to search for her expression—is she smiling, or smirking? Happy or sad?—Leonardo’s fine use of the technique he termed sfumato makes this impossible to tell. Similarly, the mask with eyes and mouth softened to create ambiguity “is extremely effective in stimulating our neural visual responses and creating active and engaged spectatorship.” Masks were frontally directed even in speech; and everything—gesture, dance and movement—was synchronized and finely coordinated with whatever was being sung or spoken. Thus, the masked actor amplifies our visual response not only to the face but to the entire body.

We’re reminded how the direction of light affects the expression of a Japanese Noh mask, and we imagine that one reason for the detailed orchestration of coordinated movements was to enable a slight tilt of an actor’s masked head to reflect a different emotion.

As Meineck points out, “The mask allowed the tragic dramatist a far greater control over the presentation of the emotional content of his work, by closely coordinating masked movement with music, song, and spoken word and then allowing the ambiguity of the mask to provoke a highly personal response in the mind of each individual spectator. Their neural processing mechanisms would have been stimulated by the context of what was presented, and then fired to create a deeply personal emotional image. In this way, the visual ambiguity of the mask greatly enhanced the presentation of tragedy. Thus, the tragic mask was far more powerful than the real face of an actor, as it constantly changed, reflecting the emotional realities of each person sitting before its compelling gaze.”

As a consequence of the mask, participants would be drawn empathically to the actions and concerns of the actors, experiencing an intimate personal connection with the characters portrayed. As we mentioned before, these tales dealt ruthlessly and relentlessly with human passions, conflicts and suffering at the same time expressing Greek ideals. Watching and participating in the event would induce a cathartic experience so badly needed by the many soldiers in the audience, many of whom had participated in the long Peloponnesian war, and were very likely exposed to extreme violence, suffering and death.

Meineck proposes that the mask created the focus that guided the spectators between the foveal [the focus on the object and the details within the object] and the peripheral vision. He asserts that “the texts we have were created with the mask in mind. It was not an afterthought to the creative process of playmaking… the mask was actually the focus of the entire visual and emotional experience of ancient drama. In fact, it may not be too bold a statement to say that without the mask we might never have seen the development of narrative drama or the birth of tragedy.”

Tragedy as Therapy

In 330 BCE Aristotle wrote Poetics, in which he outlined six main elements that should be present in any artistic work in order to make it successful: plot/structure, characterization, diction/style, spectacle, song, and thought-provoking ideas. He also noted that tragedy made people feel both good and less bad; and that a therapeutic process he called catharsis was evident in the audiences of such plays.

At the time when the great plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides were first performed, many of the participants would have been soldiers, actively serving in the Peloponnesian war and suffering from PTSD. These events provided a situation and space where they could review their post-traumatic memories safely supported by all involved as they watched tales of murder, suicide, infanticide, bravery and cowardice, gods and mortals play out before them.

In the 1980s, Californian psychologist Francine Shapiro suggested that side-to-side eye movements may stimulate a small region of our brain involved in fear attenuation. This is thought to be correct. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing or EMDR is now formally recognized by the American Psychological Association, the World Health Organization and the Department of Veterans affairs.

As we said, these plays always included the chorus—a group of 12 to 50 masked actors who, acting in unison, described and commented upon the main action in both song and speech. Meineck explains that the movement of the chorus reflected the processional route creating “a dynamic and fluid theater of movement where what was ‘onstage’ and what was ‘offstage’ was more ambiguous … choruses flowing in and out of scenes, informing the narratives and moods of each—a dynamic movement-based theater.”

Angus Fletcher in his book Wonderworks also tells us that the Greek chorus gave “a dynamic performance” and that it “shifted the [audience’s] eyes left and right.” He goes on to say that “although we cannot travel back in time to gauge the therapeutic effectiveness of these long-ago treatments, we have been able to observe their healing action on 21st century trauma survivors.”

This video from Open University tells us more about “Actors in the Greek Theatre” with reference to “The Persians” by Aeschylus that was originally part of a trilogy that won first prize at the Dionysia festival in 472 BCE.

In summary, storytellers had always told versions of well-known myths, tailored to isolate and address societal problems, but now, for the first time, the words were played out by human representatives rather than just narrated. These ceremonies were religious, they included libations to the gods, music and dancing with stories now acted out by masked actors.

Plays posed questions, revealed problems, exposed human weaknesses and strengths, and provided a cathartic experience for everyone present, one that helped to facilitate transformation and change at all levels of society, whether personal or political. A goal was for everyone present to achieve a receptive state—one that is “outside oneself,” the Greek meaning of “ecstatic”—in which the actors, chorus and audience could participate “as one.”

Thus, theater became a driving force designed to keep democracy on track. With all the apparent disfunction of today, we might reflect on the ingenious ways in which the ancient Greeks employed theater to do this.