Barriers to Environmental Change, Part 2: Short-Term Thinking

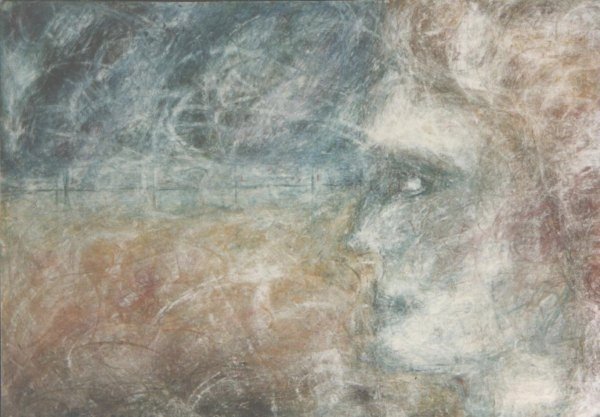

“Horizon and Vision,” by Erik Pevernagie; posted by Onlysilence, Wikimedia Commons

Human brains prioritize immediate threats while ignoring long-term crises like climate change. Combined with economic short-sightedness, inequality, and moral indifference, this mindset perpetuates inaction. How can empathy and systemic change challenge entrenched self-interest and avert environmental catastrophe?

Brains Wired for Short-Term Thinking

Thirty-five years ago, in their book New World, New Mind, Robert Ornstein and Paul Ehrlich wrote about how we are biologically wired to react to immediate danger, not to recognize and act on long-term, often invisible, facts. Nathaniel Rich, author of Losing Earth, describes how in 1985, Curtis Moore, a Republican staff member on the Committee on Environment and Public Works, told climate activist Rafe Pomerance that although global warming was an existential problem, it wasn’t a political one. Political problems, Moore said, have solutions, whilst the climate issue had none, which meant any policy could only fail. Rich writes: “No elected politician desired to come within shouting distance of failure.”

The growth-at-any-cost economic perspective is also derived from this short-term thinking. Society’s immediate need for unfettered energy production eclipses long-term environmental consequences, no matter how cataclysmic. Thus, the only future worthy of consideration is the short term.

Alarming Lack of Empathy: The Moral Issue

“Beyond an increase of 5 degrees we face the prospect of a new dark age,” writes Rich. “It is difficult to look at this fact squarely and not flinch. But doing so has a clarifying influence. It brings into relief a dimension of the crisis that to this point has been largely absent: the moral dimension … Once it becomes possible to disregard the welfare of future generations, or those now vulnerable to flooding or drought or wildfire—once it becomes possible to abandon the constraints of human empathy, any monstrosity committed in the name of self-interest is permissible.”

At a 2014 meeting of the Alliance of Small Island States, Seychelles president James Michel said, “We cannot accept that any island be lost to sea level rise… We stand as the defenders of the moral rights of every citizen of our planet.” The following year, the foreign minister of the Marshall Islands said that the islanders’ forced abandonment of their homes and cultures “is equivalent in our minds to genocide.”

The climate crisis disproportionately impacts the poor, who have contributed the least to emissions from fossil fuel combustion. While the wealthy can afford to transition to clean energy and reduce their vulnerability to extreme weather, many people around the world are still striving for the basic economic benefits that industrialized societies achieved through fossil fuel use.

Global warming is increasing economic disparities between the rich and the poor. For instance, India could have increased its GDP by nearly one-third over the past fifty years without the impacts of climate change. The Global Climate Risk Index shows that from 1998 to 2017, countries like Puerto Rico, Honduras, and Myanmar were the hardest hit, while wealthier nations, including Russia and Norway, benefited economically. In the US, low-income individuals have been more severely affected by climate change and extreme weather events, as evidenced by the impacts of Hurricanes Katrina, Harvey, and Florence.

Damage in Libya caused by Storm Daniel which caused the displacement of 45,000 and killed over 4,000. (Britannica)

The absence of empathy, combined with tribalism and narrow self-interest, hinders both local and international agreements on climate action. Each nation prioritizes its own interests, leading to compromises that often result in minimal action—reflecting the lowest-common-denominator approach characteristic of international diplomacy. As economist William Nordhaus put it: “Countries have strong incentives to proclaim lofty and ambitious goals—and then to ignore these goals and go about business as usual.”

The requisite technologies to avert crisis, says Wallace-Wells, are not additive but must be substitutive, “Which means that all of the new alternatives have to face off with the resistance of entrenched corporate interests and the status-quo bias of consumers who are relatively happy with the lives they have today.”