Alternative Currency: Substitute Moneys and Cryptocurrencies

Bristol Pounds – and example of community currency.

Currency is ephemeral and secondary; that it is the underlying mechanism of credit and repayment of accounts is the essence of money. For different reasons, alternative, unofficial currencies have served this function in place of, or alongside, government money.

As we have seen, money in the current economic system is mostly created (out of thin air) by private banks as credit (better seen as debt that borrowers have taken on), and only less than 10% is issued by governments as actual cash. When these officially recognized sources of money have dried up, or when a group of people wish to by-pass the system, alternative currency, or unofficial money appears in order to enable exchange. This money circulates as credit within a community, purely on trust that this debt will be repaid.

- What happens when bank credit or government money disappears?

- When, why and where has unofficial money appeared?

- Can money exist without stabilisation by a political power?

- How does modern technology help?

Money, Not Created by Banks, Nor Backed by the State

Community Credit in Ireland, 1970

On May 4, 1970, a notice appeared in Ireland’s leading newspaper, with the alarming title: “Closure of Banks.” Due to a labour dispute, the banks had all stopped providing any services.

In Money: The Unauthorised Biography, Felix Martin writes “From the beginning, it was expected that the banks’ closure would not be short-lived, so preparations were made… to stockpile notes and coins…the Central Bank of Ireland noted that prior to the closure ‘some two-thirds of aggregate money holdings are in the form of credit balances on current accounts, the remainder consisting of notes and coin.’ The critical question…was whether this ‘bank money’ would continue to circulate.

“For individuals in particular, there was really no other option: for any expenses in excess of the cash they had in hand when the banks shut, their only hope was to write IOUs in the form of cheques and hope that they would be accepted.

“Remarkably, as the summer wore on, transactions continued to take place and cheques to be exchanged almost exactly as usual. The one difference, of course, was that none of the cheques could be submitted to the banks…

“Normally, this facility is what relieves sellers of most of the risk of accepting credit payments: cheques can be cashed at the end of every business day. With the banking system shut, however, cheques were for the time being just personal or corporate IOUs. Sellers who accepted them were doing so on the basis of their own assessment of buyers’ credit…

“Since cheques were not being cleared, there was nothing in principle to prevent people writing cheques for amounts that they did not have. For the system to work, payees would have to take it on trust that payers’ cheques were not going to bounce…a highly personalized credit system without any definite time horizon for the…clearance of debits and credits substituted for the existing institutionalized banking system.

“In the end, the main impediment imposed by this highly successful system turned out to be logistical…an enormous volume of uncleared cheques had accumulated…It was another three months – until mid-February, 1971 – before matters had returned completely to normal.

“How had this apparent miracle of spontaneous economic co-operation come to pass? The general consensus after the event was that several features of Irish social life were uniquely conducive to its success…The basic challenge was that of screening the creditworthiness of those paying by unclearable cheque...‘It appears,’ concluded the Irish economist Antoin Murphy… ‘that the managers of these retail outlets and public houses had a high degree of information about their customers – one does not after all serve drink to someone for years without discovering something of his liquid resources.’”

…Currency is ephemeral and secondary; that it is the underlying mechanism of credit and repayment of accounts that is the essence of money.

Over £5 billion of unclearable checks were accepted in six and a half months. Insofar as these checks were countersigned and used for payment from person to person, they became, in effect, currency. For currency is transferable debt. But this communal credit in the country of Ireland, which had a population of about 3 million at the time, was only possible because of the trust which a close-knit society made available. It could not occur in a larger, or less face-to-face culture. Small size is an advantage here.

It also showed that currency is ephemeral and secondary; that it is the underlying mechanism of credit and repayment of accounts that is the essence of money.

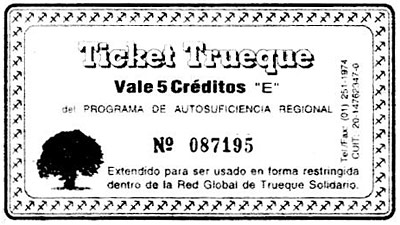

Substitute Money Tokens in Argentina, 2001

Unlike Ireland in 1970, where the banks closed, the government of Argentina cut access to cash in December 2001 because it was overwhelmed by a currency crisis. Some years previously, the politicians had pegged the value of the Argentinean peso to the US dollar, and when its largest export market, Brazil, devalued in 1999, Argentina inevitably fell into recession. Then, as the US dollar rose over the next two years due to a US credit bubble, the peso rose with it – heaping more misery upon the country.

By mid 2001 Argentina had been in recession for three years and still the economy continued to shrink. Private capital fled the country and pesos became increasingly scarce, causing a run on the banks. Felix Martin writes “To preserve the liquidity of the banks, a strict limit was imposed on the amount of cash that depositors could withdraw from their accounts. It was a desperate measure that…succeeded in preventing the imminent collapse of the banking system – but at the cost of causing an immediate and acute shortage of peso liquidity.

“The Argentinian public’s response to the sudden drought of money was no less entrepreneurial than that of the Irish had been thirty years before. Where the state would not oblige, substitute moneys sprang up spontaneously. Provinces, cities, and even supermarket chains started to issue their own IOUs, which rapidly began to circulate as money…By March 2002, such privately issued notes made up nearly a third of the all the money in the country.

“The monetary authorities were mortified…In Ireland, the government had been trying earnestly to prevent the shutdown of the monetary system...In Argentina, it was the government itself that imposed the effective closure of the banks…to forestall a run and to prevent the flight of capital into foreign currencies”

Many people held that these policies were harmful and illegitimate. That instead of caring for its citizens, the government was working for the blood-sucking usurers and foreign capitalists. The creation of quasi-currencies enabled trade to continue, despite the lack of official pesos, and these quasi-currencies were seen as an act of open defiance of the government’s draconian monetary policy.

Through the ages, a shortage of cash has often led to the use of private tokens, sometimes called scrip.

At last, in 2002, the peso was detached from the US dollar, and could sink down in value. People lost wealth by the devaluation, but the peso became plentiful again. There was no longer a need for the raft of quasi-currencies, and they disappeared.

This is only one of the latest examples where unofficial moneys have been substituted for scarce government currency. Through the ages, a shortage of cash has often led to the use of private tokens, sometimes called scrip.

Complementary or Community Currencies

Recent political dissatisfaction has prompted many complementary or community currencies to come into use. This increased after the financial crash of 2008. But it has a long history, and there are thousands of local currencies all over the world, most on a limited scale. There are Local Exchange Trading Schemes (LETS), Mutual Credit Networks, Community and Business Cooperative organizations. Most alternative currencies are the work of enthusiasts, and like their cousins, utopian communities, they have mostly been small and short lived.

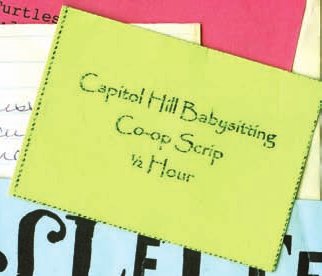

But there is a huge variety, ranging from the long-lived Swiss WIR mutual credit network, a large and sophisticated club of small businesses, to small Local Exchange Trading Schemes, and even the humble babysitting circle

In Rethinking Money: How New Currencies Turn Scarcity into Prosperity, Bernard Lietaer and Jacqui Dunne argue that the current system of money creation is unsustainable and that complementary currencies are essential for the development of a stable monetary ecosystem. They comment on the thousands of local currencies that have sprung up and show how such currencies counterbalance the intrinsic instability of the prevailing monetary system; a dreadful system based on bank debt and the assumption that money is a commodity, a scarce commodity, rather than an unlimited technique for maintaining economic relations (not a thing, but a process). Changes have come about by people simply rethinking the concept of money. With this restructuring, everything changes.

WIR Complementary Currency

The Swiss WIR, is an independent complementary currency system that serves Small and Medium sized Enterprises (SME). “Wir” means “we” in German, and is short for Wirtschaftsring, which means “Economic Circle.” The WIR offers a clearance mechanism in which businesses can buy from one another without using Swiss francs. It issues and manages a private currency, called the WIR franc, which is now a purely electronic currency. It is also used in combination with the Swiss franc to generate dual-currency transactions.

WIR was founded in 1934 by a small group of Swiss entrepreneurs who saw their turnover evaporate during the great depression. The founders were inspired by Silvio Gesell, according to whom money should be free of interest. Originally a not-for-profit cooperative, WIR changed its status as it expanded, and by 1952 it began to charge interest on loans, but at the low rate of 1.5%. In 1998, it changed its name to the WIR Bank.

[WIR is] a shining example of a business-to-business closed loop payment system currency.

It now has over 60,000 users (17% of Swiss businesses): 45,000 SMEs and 15,000 individual employee owners. Together they generate a turnover of over 1.5 billion Swiss francs per annum, a shining example of a business-to-business closed loop payment system currency. In the 1960s, this was almost undermined by speculation, when some members began trading WIR credits at a discount. However, in 1973 an extraordinary general meeting banned this practice and the WIR was saved.

Working alongside the commercial banking system, the WIR bank claims it helps to stabilise the Swiss economy by remaining fully operational during economic crises, thus counteracting downturns in the business cycle.

Community Currencies and LETS

Unlike the substitute moneys in Argentina, which appeared because of a shortage of official money, or the reaction of WIR to economic orthodoxy and the 1930s slump, Community Currencies and Local Exchange Trading Schemes (LETS) have mostly been started by people who wished to achieve social ends. They have formed mutual credit networks in order to benefit the local community, and even if there has been no particular lack of official currency at the time, they have been designed to help those with little official money to trade goods and services within their community.

This emphasis on the local community is both an advantage and a disadvantage. It encourages a tradition of trust within a community. However, it is cut off from transactions with the rest of the world (though this could be seen as an advantage, as tax is not levied on LETS transactions). Some have issued private money tokens, others have traded using a community currency which is issued and transferred on an electronic ledger. Here are some examples.

CamLETS, of Cambridge UK

Launched in 1993, CamLETS has remained a small system, with about 150 members. Its website states: “CamLETS enables members to exchange skills by means of a sophisticated barter system. You get things done for yourself by doing things for other people. …It is a way a community can trade skills, services or goods without needing or using real money. It’s a bit like a barter system, but you don’t have to do a direct swap – instead you use a local Complementary Currency. We trade using a currency called CAMS…

“If you do something for another member, the rate is usually 10 cams per hour. They will either fill out a row on a spreadsheet at a trade event, or record it as a transaction directly on the website. The amount will then be credited to your account…

“Almost all LETS trading is of an ‘occasional social favour’ type and not taxable. Only if you trade in cams as part of your regular business would you be liable to tax…

“Can I buy and sell things? Yes, and you can advertise in your listings, which are broadcast out to members at regular intervals, or at one of our social gatherings. It’s a good way of making friends.”

Of the 150 members, about 50 are regular users, and the system is still going strong. It forms a social network, but in a busy urban environment, it also suffers from the problem which Oscar Wilde identified, when he quipped that “The trouble with Socialism is that it takes too many evenings.“

The Bristol Pound (£B) UK

The Bristol Pound is a more ambitious community currency, its website calls it “money that’s made by local people, for local people. It’s run by a non-profit community interest company (Bristol Pound CIC) in partnership with the Bristol Credit Union.

“Set up by a group of campaigners and financial activists in 2009, the Bristol Pound is a network of over 2,000 individuals and independent businesses who use digital and paper currency to trade in Bristol, localising supply chains and keeping money circulating in our city. It’s a movement, an idea, a hope, a better way of doing money.

“The financial crisis in 2008 was a wake up call for many of us. We came to realise that our city’s economic system extracts wealth from communities, harming the real local economy. It damages the environment, perpetuates inequality and homogenises high streets into unrecognisable, carbon clones.

“…The Bristol Pound was established as a movement driven by the community, which aims to redefine the way we live and work with money.

“…Since its birth, over £5 million Bristol Pounds have been spent in the city, including paper and electronic payments. Over 80,000 transactions have been made by text, mobile app and online banking, which is around 300 payments a week since 2012. Members can use Bristol Pounds to get on the bus or train, to pay their council tax, to buy their vegetables, coffee and bread. The Bristol Pound’s very existence is proof that bottom up community organising works, and that together, we can create a greener, fairer and stronger local economy.”

According to the Community Currency Knowledge Gateway, “it is the first city-wide instance of a Transition Currency in the U.K…The model is very similar to other Transition Currencies in Brixton, Stroud, Lewes and Totnes UK, Regiogeld in Germany and the BerkShares in the U.S.

The Bristol Pound is a reaction to the damage done to local businesses by large chain stores, by internet shopping, and by globalisation.

“…Bristol Pound can be used to pay council tax, business rates, staff wages, and business and professional services…Bristol’s first elected mayor…receives his full salary in Bristol Pounds.”

The Bristol Pound is a reaction to the damage done to local businesses by large chain stores, by internet shopping, and by globalisation. It aims to strengthen the local economy, as the website says, “by ‘locking’ money into the city so it does not leak out through chain stores…It is this continual circulation of money within the local economy that really builds the benefits of the Bristol Pound and makes it much more valuable than spending sterling.

“We create more wealth because less money leaves Bristol and gets lost in complicated global financial systems. Sterling isn’t loyal; it goes wherever it can make more of itself, accumulating in tax havens, in big executive pay packets or with distant shareholders. Bristol Pounds stay working on the ground for us. They stick to Bristol creating stronger communities and a greener economy.”

Some years on, the Bristol Pound now claims to be the largest local currency in the UK, and though it is still not a major force in the city, it is well organized and has 1,500 enthusiastic consumer members and over 650 business participants.

Ithaca HOURS, USA

The upstate New York college town of Ithaca has its Ithaca HOURS. Launched in 1991 by Paul Glover, this is the oldest operating complementary currency in the United States. An HOUR is valued at $10, the average hourly pay in Ithaca at the time.

Glover hoped that the HOURS project would keep money in the local economy, and avoid the social and economic costs which he associated with the increasingly global financial system. Glover promoted the HOURS aggressively, and by the end of the 1990s, hundreds of local businesses had pledged to accept the new currency.

The current revival of local currency is due to communities’ idealistic attempts to extricate themselves from the troubled economy.

The HOURS system relied on the evangelism of its founder, who worked full-time to educate residents and business owners about the uses for HOURS. The rise in electronic payment systems, plus his departure from Ithaca, contributed to a steady decline in the use of HOURS.

Local currencies like this were mostly outlawed by Congress in the late 18th century but enjoyed a brief revival during the Great Depression. The current revival is due to communities’ idealistic attempts to extricate themselves from the troubled economy.

Cryptocurrencies – Bitcoin

Substitute money and community currencies have been useful locally and for relatively short periods of time. But could a democratic currency, independent of central control, ever challenge the orthodox form of money – the money of the powerful – the money of politics? For who would issue the currency and regulate its quantity and quality if not a government or central bank – whether these are captured by the power elite or are under democratic control?

The rise of the internet brought on the prospect of a democratic, safe and honest digital currency with no physical form. Perhaps it could exist in everyone’s computers and smartphones, independent of any central control. Perhaps it could become an international currency, unconstrained by borders or national politics.

But unlike a coin, or an entry in a central ledger, such non-physical money, distributed across the internet, is vulnerable to easy counterfeiting, for it is just represented by a string of numbers.

The challenge was: how to make an electronic currency which cannot be copied. How to encrypt each and every transaction so it will remain secure in an open system and not be stolen. How to ensure that we only spend what we have – not spend the same money twice.

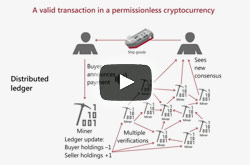

In Talking to My Daughter about Economics: A Brief History of Capitalism, Yanis Varoufakis writes: “A brilliant answer to this question was sent in an email to an online chatroom on 1 November 2008, a few weeks after the crash hit. The email was signed by Satoshi Nakamoto, a pseudonym hiding a person or team whose identity hasn’t been uncovered to this day. In this email Nakamoto presented a dazzling computer program – an algorithm – that solved this problem and would become the basis for a new decentralized digital currency – the so-called Bitcoin.

“Before Nakamoto’s email all other solutions required a central authority of some kind. Banks and credit card companies like Visa or Mastercard deal with the problem by creating a central digital spreadsheet. Every time you pay for something from Amazon using my credit card, a number of dollars is taken out of the entry in that central spreadsheet – or ledger – next to my name and account number and is put next to Amazon’s name and account number on the same central spreadsheet. Before every purchase I make, the central system checks to see that there are sufficient funds next to my name, ensuring I never spend the same money twice.

“The beauty of Nakamoto’s algorithm was that it did away with the ledger run by a central authority but still managed to ensure that a single currency unit could never be copied or spent twice.

“Who would take responsibility for policing transactions then?… The fascinating answer is, everyone! The whole community using Bitcoin would share in the task by each making available a small part of their computer’s capacity for this purpose. Everyone would observe everyone else’s transactions, ensuring their validity, while at the same time no one would know whose transactions they were observing, safeguarding privacy.”

Nakamoto set an arbitrary limit to the total number of Bitcoins – there can never be more than 21 million of them, unlike fiat currency.

This distributed security system is the essence of Bitcoin. It is based on software called the Blockchain which works on the internet, building a secure peer-to-peer network. Every Bitcoin transaction is recorded on a public ledger which resides on the network and is accessible to all Bitcoin users.

Thanks to some nifty cryptographic techniques, it is impossible in practice to tamper with any new transaction added to the ledger, and since the ledger is public, it can be viewed by anyone at any time. The result is a currency that is trustworthy, without being backed by any one organisation, bank or government.

This Blockchain based currency is dependent on two more features:

- Every Bitcoin can only be created by someone’s computer solving a cryptographic puzzle. So it is that whoever owns this computer gains (becomes richer by) one new Bitcoin when the computation is complete.

- Nakamoto set an arbitrary limit to the total number of Bitcoins – there can never be more than 21 million of them, unlike fiat currency.

Creating Bitcoins by solving cryptographic code is called “mining,” and like mining for gold, the process is difficult. At the beginning, mining was easier, and early miners became rich. But now the computations are increasingly arduous. So they are undertaken by wealthy consortiums in warehouses full of computers, consuming vast amounts of electricity. The New Scientist reported in 2017 that Bitcoin mining uses more electricity than the whole country of Ecuador.

And like gold, it is not something with which one can go out and buy a sandwich or a pair of shoes in most places. Not until people are paid in Bitcoin can it become a general currency, and that is unlikely to happen soon.

So far, Bitcoin has been subject to enormous price fluctuation. For instance, in 2011, the value of one bitcoin rose rapidly from about $0.30 to $32, before returning to $2. Later it surged to $1,242. In 2014 its volatility was seven times greater than gold. It has yet to settle down, for from about $750 in December 2016 it rose to nearly $20,000 in December 2017, only to fall to just over $4,000 in December 2018. Then, in 2021, it skyrocketed to over $67,000, only to dive down again to $30,000 a year later.

In January 2024, when the US Securities and Exchange Commission approved Bitcoin as an exchange-traded fund (ETF), its value briefly spiked to $47,000. But this approval does not transform crypto currencies into officially designated currencies. It just increases their volatility in the market by allowing ETF agents to act like bookies, handling bets on its perceived value – a dangerous development for the unwary.

At present it remains largely a vehicle for speculation, and there are many who have grown rich, or lost their money, by gambling on its wild fluctuations.

Also, Bitcoin’s anonymity makes it the perfect vehicle for money laundering and financial scams. Joseph Stiglitz says that: “If you open up a hole like Bitcoin, then all the nefarious activity will go through that hole, and no government can allow that.” He’s also said that if “you regulate it so you couldn’t engage in money laundering and all these other [crimes], there will be no demand for Bitcoin. By regulating the abuses, you are going to regulate it out of existence. It exists because of the abuses.”

In 2016, $70 million worth of Bitcoin was stolen from customer accounts held at Bitfinex. As the Financial Times wrote, that “should give the banking industry pause for thought with respect to adopting blockchain and Bitcoin-based financial technologies.”

“…If robbers break into a normal bank…, the law ensures that your deposits are safe, but with Bitcoin being outside the jurisdiction of any state, no one will come to your rescue…”

About regulation, Yanis Varoufakis writes “What is truly interesting about this…is that it reminds us why money is, and must always be, political. That money is political is not something Bitcoin’s supporters dispute. Their love for Bitcoin…stems from what they see as its anarchic, anti-establishment, counter-authoritarian nature.

“This is as political as it gets. What Bitcoin supporters would not like, however, is what I am going to say next: that money can be kept separate from the state and from the political process…is a dangerous illusion.

“…If robbers break into a normal bank…, the law ensures that your deposits are safe, but with Bitcoin being outside the jurisdiction of any state, no one will come to your rescue…We might dislike it, but the state is ultimately our only insurance policy against organized crime. However, this is not the most serious weakness of stateless currencies like Bitcoin.

“Their greatest and most dangerous weakness is that, because they are founded on the notion that no intervention in the money supply should be possible lest this intervention be manipulated by governments or bankers, it is impossible to adjust the total quantity of money…in response to a crisis – and this makes a crisis worse, as we have seen…

“Bitcoin’s algorithm specifies that the number of Bitcoins in existence is fixed… the quantity grows slowly until it reaches a maximum number – 21 million Bitcoins sometime in 2032.… But this…makes a crisis more likely and…it makes it harder to alleviate the crisis when it hits.

“Let’s…see why the fixed quantity of Bitcoins makes a crisis more likely…As businesses create more products, each Bitcoin will become relatively scarcer and so be worth more and more. Which means that the price, measured in Bitcoins, of each car or gadget falls…price deflation. This is not a problem in and of itself, but becomes a huge one if wages fall faster than prices, meaning workers can only afford to buy fewer of the multiplying products. This fall in sales due to Bitcoin’s deflationary effect adds…to the bankers’ standard overexuberance and sparks a crash more readily.

“Once the crash has happened, the second problem of a Bitcoin-powered economy emerges: the impossibility of reflating the economy by increasing the quantity of money. After a crash, when the money that bankers had conjured up from the future fails to materialize, the government must replace some of that missing money quickly, bailing out banks (though not the bankers) and spending on the poor, on public works and so on.

“Unless it takes swift action to increase the money supply, the chain reaction of insolvencies will push everyone into a 1930s-like slump. But such swift action is not possible under Bitcoin, whose supply is fixed and outside the authorities’ grasp…

It is this apolitical nature of Bitcoin that is its Achilles heel. Like gold, the quantity of Bitcoin is finite and cannot fluctuate in response to political needs.

“It is what happened before and after the crash of 1929, when governments were determined to keep the money supply in unchanging proportion to the amount of gold they possessed – a policy known as the Gold Standard, which is very close in spirit to the aversion to political money that lies behind Bitcoin. It was only after the British government in 1931 and President Roosevelt…in 1933 decoupled the quantity of currency from gold…that some relief came.”

It is this apolitical nature of Bitcoin that is its Achilles heel. Like gold, the quantity of Bitcoin is finite and cannot fluctuate in response to political needs. Some don’t see this as a failing, but this inflexibility makes it unsuitable as general purpose money, and so long as we live in independent states, money will remain a crucial tool of politics.

Many will be disappointed that cryptocurrencies, like every other form of unofficial money, will not pry the control of money out of the hands of bankers. For it is undoubtedly true that both governments and bankers misuse their control of money creation. Governments reduce the value of their obligations by fostering inflation, thus devaluing the currency of their citizens. Banks take outrageous risks to gain vast profits, knowing that, being too large to fail, they will be bailed out by the taxpayer. Meanwhile, the advocates of unofficial money wish that, somehow, money could be detached forever from the norms of politics.

But for the hopeful speculator, Bitcoin has spawned hundreds of copycat currencies, all based on the Blockchain idea, such as Etherium, Ripple and Litecoin. So far their values have yet to settle, and many traders have made fortunes by them. Which ones will survive, and whether they will serve any useful purpose, beyond a gamble in the casino that is today’s financial sector, is uncertain.

Perhaps it is by Blockchain network technology that the real gains will be made. For it has now spread to other areas, such as voting systems and the tracking of the provenance of food products, where its security and anonymity could be vital.

Mobile Phone Money

In countries like Kenya, Somalia or Afghanistan, banks are few and far between. People have had little or no access cash or banks. For the poor, this put a brake on trade. People remained at the mercy of corruption, unable to receive money securely or pay for what was needed.

By an imaginative leap, mobile phones changed all that.

As Tim Hartford explains on the BBC, “When 53 police officers in Afghanistan checked their phones in 2009, they felt sure there had been some mistake. They knew they were part of a pilot project to see if public sector salaries could be paid via a new mobile money service called M-Paisa. But had they somehow overlooked the detail that their participation brought a pay rise? Or had someone mistyped the amount to send them? The message said their salary was significantly larger than usual.

“In fact, the amount was what they should have been getting all along. But previously, they received their salaries in cash, passed down from the ministry via their superior officers. Somewhere along the line, about 30% of their pay had been skimmed off. Indeed, the ministry soon realised that one in 10 police officers whose salaries they had been dutifully paying did not exist.

“The police officers were delighted to be getting their full salary. Their commanders were less cheerful about losing their cut.

“Afghanistan is one of a number of developing countries whose economies are currently being reshaped by mobile money – the ability to send payments by text message.

“The ubiquitous kiosks that sell prepaid mobile airtime effectively function like bank branches: you deposit cash, and the agent sends you an SMS (Short Messaging Service, or text message) adding that amount to your balance. Or you send the agent an SMS, and she gives you cash. And you can text some of your balance to anyone else.

“It is an invention with roots in many places. But it first took off in Kenya, and that story starts with a presentation made at the World Summit for Sustainable Development in Johannesburg in 2002 by Vodafone’s Nick Hughes. His topic was how to encourage large corporations to allocate research funding to ideas that looked risky but might help poor countries’ development.

“In the audience was an official for the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID) which had money to invest in a ‘challenge fund’ to improve access to financial services.

“DFID had noticed the customers of African mobile networks were transferring prepaid airtime to each other as a sort of quasi-currency. So the man from DFID had a proposition. DFID would chip in £1m, provided Vodafone committed the same. That got the attention of Mr. Hughes’s bosses.

“But his initial idea was not about tackling corruption in the public sector. It was about something much more limited – microfinance, a hot topic in international development at the time. Hundreds of millions of would-be entrepreneurs were too poor for the banking system to bother lending them money. If only they could borrow a small amount – enough to buy a cow, or sewing machine, or motorbike – they could start their own business.

“Mr. Hughes wanted to explore microfinance clients repaying their loans via SMS. By 2005, Mr. Hughes’s colleague Susie Lonie was in Kenya with Safaricom, a mobile network part-owned by Vodafone. She recalls conducting one training session in a sweltering tin shed, and the incomprehension of microfinance clients. Before she could explain M-Pesa, she had to explain how mobile phones worked.

“But once people started using the service, it soon became clear they were using it for much more than repaying microfinance loans. One woman in the pilot project texted some money to her husband after he was robbed, so he could catch the bus home. Others said they had used M-Pesa to avoid being robbed, depositing money before a journey and withdrawing it on arrival. Businesses deposited money overnight rather than keeping it in a safe.

“M-Pesa is a textbook ‘leapfrog’ technology: where an invention takes hold because the alternatives are poorly developed.”

“People paid each other for services. And workers in the city used M-Pesa to send money to relatives back home: much safer than the previous option, entrusting the bus driver with an envelope of cash.

“Ms. Lonie realised they were on to something big. Just eight months after its launch, a million Kenyans had signed up to M-Pesa. Today, there are about 20 million users.

Now nearly half of GDP in Kenya is transacted through mobile digital payments.

“Within two years, M-Pesa transfers amounted to 10% of Kenya’s gross domestic product (GDP) – now it accounts for nearly half. Soon, there were 100 times as many M-Pesa kiosks in Kenya as cash machines.

“M-Pesa is a textbook ‘leapfrog’ technology: where an invention takes hold because the alternatives are poorly developed. Mobile phones allowed Africans to leapfrog their often woefully inadequate landline networks. M-Pesa exposed their banking systems, typically too inefficient to turn a profit from serving the low-income majority.”

M-Pesa (M for mobile, pesa for money in Swahili) and other mobile phone money systems have now spread all over Africa and to countries like Afghanistan, Albania and India. And now nearly half of GDP in Kenya is transacted through mobile digital payments. Despite significant charges by the phone companies, mobile phones have unleashed a vast flow of transactions which had previously been stifled for lack of suitable money; raising the living standards of the people.

The Decline of Cash

Loss of anonymity cedes tremendous power to both government and the banks, who now know what, where and when we buy.

In the past few years, the use of cash for everyday transactions has fallen precipitously all over the world as contactless card payments and mobile phone payments have become accepted. Indeed, the number of payments made by card in the UK now equals those made by cash, having been five times less only ten years ago, and more than a third of people in the US say they carry cash rarely or never.

However, unlike cash, and like any electronic payment system, be it by credit card or mobile phone, such payments are not anonymous. Now every transaction can be tracked by central authority. This loss of anonymity cedes tremendous power to both government and the banks, who now know what, where and when we buy. Whether this is used for good or for ill depends on how our politics evolves. For nothing is ever certain.

In the series: Trust, Faith and Confidence–Value and the Role of Money

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

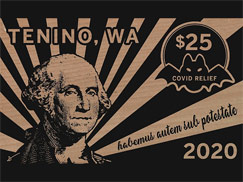

Covid Currency

The Apopka Voice

In a bid to lessen the blow of COVID-19, the town of Tenino has started issuing its own wooden dollars that can only be spent at local businesses. Will it work?

Watch: Cryptocurrencies: Looking Beyond the Hype

Bank for International Settlements

Cryptocurrencies’ decentralised model of generating trust limits their potential to replace conventional money.