Adolescence: Challenges and Opportunities

Millions of people gathered around the world in March for Our Lives rallies organized by high school students. Photo by Phil Roeder

A second and final brain growth spurt occurs during adolescence, making this another optimal period for learning. It is a crucial time when young people are especially sensitive to their experiences. To successfully transition into adulthood, young people need more insight into what they are experiencing; they also need relevant educational opportunities, meaningful work, and caring adult interaction and guidance.

During adolescence, bodily changes are apparent; equally significant but less obvious are transformations in the brain. Cognitive abilities expand, risk and reward centers become increasingly important, and self-regulation may be challenging. Peers wield considerable influence, while the impact of teachers and other adults may diminish. Empowering experiences, mentoring, real-world challenges, and stimulating education can help adolescents transition into a healthy adulthood.

During adolescence, the brain is more plastic and so more easily shaped by experiences than at other times in our lives. Also, brain circuits that are no longer used are eliminated, so it appears to be the best chance in life to learn new skills and develop lifelong habits. Of course, learning new skills and developing old ones is possible throughout our lives, but this becomes more difficult in adulthood.

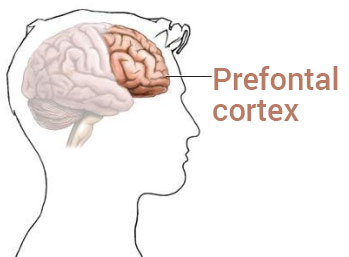

During adolescence the prefrontal cortex, responsible for self-control, judgment, organization, planning and emotional control undergoes the most change. Unsurprisingly, as it gradually matures, young people tend to find these skills difficult to manage.

Functions of the Prefrontal Cortex

The prefrontal cortex is responsible for executive functions, or goal-directed behavior:

- Decision making

- Initialization and control over the execution of deliberate actions

- Targeting attention

- Problem solving

- Planning initiation of activities

- Processes in working memory

- Social Behavior/Reasoning

When an action is executed, the prefrontal cortex is informed and allows appropriate monitoring. A feedback-feedforward loop helps judge activity and reveals possible deficiencies.

Opportunity for Positive Growth

The psychologist Laurence Steinberg of Temple University, has specialized in child and adolescent psychological development for the last 40 years. He says that adolescence should be conceived of as lasting from puberty to the early 20s; he views it as a unique opportunity for positive growth which is too often squandered, in part because adults tend to think of it as a time both they and their children have to survive. Steinberg says that until teens learn to “brake” their “overactive engines,” they need support, guidance and sympathetic understanding.

Brain imaging demonstrates that the reward centers of adolescent brains “light up” more in response to potential rewards than do either child or adult brains.

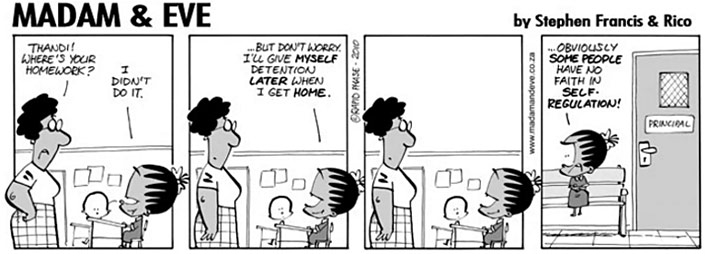

“The capacity for self-regulation is probably the single most important contributor to achievement, mental health, and social success. The ability to exercise control over what we think, what we feel, and what we do protects against a wide range of psychological disorders, contributes to more satisfying and fulfilling relationships, and facilitates accomplishment in the worlds of school and work. … This makes developing self-regulation the central task of adolescence, and the goal that we should be helping them pursue as parents, educators, and health care professionals.”

Researchers have also found that the prefrontal cortex is involved in the developing sense of self, in learning to attribute complex mental states such as intentions both to oneself as well as to other people.

One of the notable things Steinberg found is that adolescents are also more primed than either children or adults to respond to rewards. The reward centers of adolescent brains “light up” more in response to potential rewards than they do in either child or adult brains. This, plus the fact that the brain’s malleability enables it to assimilate new information and skills more easily, suggests that though boundaries are essential, reward-based challenges would be more successful than threat and punishment-based rules, and at the same time would add positively to a young person’s developing sense of self.

“The capacity for self-regulation is probably the single most important contributor to achievement, mental health, and social success.”

Adolescence is a time when we are especially sensation seeking. Research shows that an adolescent’s ability to judge the risks and potential dangers of a decision or situation is not that much different from that of an adult’s. It’s just that adolescents are more prone to taking risks because of psychosocial factors that affect their still-developing ability for self-regulation. Adolescents have the same response to the sensation of risk as they do to the sensation of reward. That response simply overrides any judgement or conscious decision-making and makes them more likely to disregard potential hazards. This effect is heightened in the presence of peers because peer approval is experienced as a reward.

This “peer pressure” can work for or against them. If teenagers perceive, for example, that risky driving makes them more attractive or that engaging in unprotected sex makes them appear more faithful, and those images are important to their personal identity within their peer group, they may decide to engage in those behaviors despite their awareness of the risks. If we understand this about adolescents, we can focus interventions that capitalize the upside and reduce the harm associated with the risk-taking behavior that is more or less part of the adolescent self. Providing young people with information about what’s happening to them developmentally may also help them regulate both their extreme self-consciousness and propensity to take dangerous risks.

With what is now known about adolescence, it’s clear that the middle and high school years are an ideal time for motivational learning. They provide the opportunity to challenge young people, giving them the chance to experiment in safety as they learn to collaborate with their peers to achieve goals, as well as to pursue their passions, talents and potential independently.

Says civil rights veteran and mathematician Robert Moses, founder of the Algebra Project that teaches higher math skills to some of the most marginalized students, “You have another shot at the kids as they enter their peer group in high school. If you get the peer group’s culture to work for the kids, then you have an important and really powerful engine for getting the kids to figure out that they need to set their own expectation for what they need to do as they go through high school.”

Lessons from Parkland

The nationwide “March for Our Lives” movement that sprang up almost spontaneously after the tragic Parkland school shooting on Valentine’s Day, 2018, is a remarkable example of the positive potential of adolescents.

Writes David Cullen in Parkland: Birth of a Movement: “It was speed that launched this movement, and a breadth of talent that packed its punch. That first night, Cameron [Kasky], Jackie [Corin], and David Hogg started simultaneously on separate tracks to completely different movements, which they fused forty-eight hours later to form a juggernaut. Cameron’s first and best move was assembling talent. By Saturday, when Emma González went viral [with her ‘We call B.S.!’ speech], two dozen creatives were conjuring up a new movement in Cam’s living room.”

As a high school senior, David Hogg was already a working journalist. He was news director at the school’s TV station WMSD and had just landed a gig as a stringer for the Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel. On that Wednesday afternoon, Emma Gonzalez’ AP U.S. government class had focused on special interest groups, and just before the shooting, she had been thinking about gun safety and the NRA. As their team began to coalesce, David saw the need for a strong implementer. He called in his friend Jackie Corin—only to find out that by Thursday, unbeknownst to him, Jackie had already made contact with Florida congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz and Parkland’s state senator Lauren Book about crafting a bill for the state legislature. She was already in the process of organizing busloads of kids to descend on Tallahassee. As Cameron told the New Yorker, “We’re strong, but together we’re unstoppable.”

The Parkland kids were well aware that as horrifying as it was to have 17 of their peers killed in a single afternoon, over 1,700 kids were killed or injured by guns in the first half of 2018, mostly in the inner cities. Right out of the gate, they framed the problem not as one of school shootings, but as fighting gun violence for all kids. Within a couple of weeks, they were meeting in Emma’s living room with D’Angelo McDade, Alex King and other kids from the Chicago-based organizations BRAVE (Bold Resistance Against Violence Everywhere) and Peace Warriors. In just a few weeks this powerful coalition of young people pulled off a March for Our Lives (MFOL) attended by some 470,000 people in Washington and 1.4 to 2.1 million people in 763 locations nationwide.

Over 1,700 kids were killed or injured by guns in the first half of 2018.

In the months following the march, they mobilized millions of kids into a vast grassroots network to get out the vote for the November midterms. Their efforts paid off with a significant surge in youth voting and in candidates of both parties running—and winning—on gun safety. The youth vote contributed to Democrats taking control of the House to begin implementing their agenda. And their efforts had clearly helped to disrupt the once impenetrable power and influence of the NRA.

As Dr. Alyse Ley, director of the child and adolescent psychiatry fellowship program at Michigan State University said to David Cullen, “Adults will always think of ten thousand reasons why you can’t do something. Kids won’t do that. That’s what’s glorious about young people: the still-developing impulse control. They see something, they see a cause, and they say, ‘I’m going to do what’s right. You’re not going to stop me.’”

As these Parkland students demonstrate, young people everywhere need to understand the relevance of what they are doing and learning in school, and school should prepare them for the real world, in part by mirroring it. The demand placed on students once they enter the workplace is likely to increase. They need to develop focus, rigor and coherence while in school, spending sustained time on problems, as they will do in the real world.

Unfortunately, the vast majority of students in U.S. high schools find classes boring and repetitive. In a 2006 study of 25 towns and cities with high drop-out rates, 81% of students said they may not have dropped out if their classes had been relevant to real life. Ironically, 88% of these students had passing grades or higher. Only one out of every six high school students in the U.S. reports ever having taken a course that was difficult or challenging. In 2017, a group of researchers looked at the issue from the point of view of young dropouts themselves and published an insightful account of their stories. Although most reported enjoying school as young children, “Strikingly, most young people we interviewed could not recall a single engaging learning activity during all of middle school.”

Although the high school dropout rate fell to an all-time low of 6.1% in the 2015-16 school year, that figure still represents some 530,000 students leaving school without graduating. In 2017, the employment rate for young adults without a high school diploma was just 57%. Even among those who do graduate and move on to college, almost two-thirds arrive unprepared for the rigor of college-level studies. A large proportion of American college graduates are obtaining degrees from for-profit universities of questionable quality.

School and Rising Stress

It’s not as if teenagers don’t care about their future or don’t understand that they must do well – quite the contrary. Children as young as 5 years old are experiencing performance pressure, and this is particularly so in adolescence. Dr. Stuart Slavin, a pediatrician and professor at the Saint Louis University School of Medicine, noted an unprecedented rise in stress levels in children of all ages and across the socioeconomic spectrum. In a 2014 survey, 94 percent of college counseling directors reported that they were seeing rising numbers of college students with severe psychological problems.

Of course, many children of poverty face the most basic of life stressors such as hunger, parental unemployment, homelessness, and everyday life in unsafe neighborhoods. As Baltimore English teacher Daniel Parsons wrote in a 2019 op-ed: “Standards do matter. But, they are totally worthless if children are so exhausted by their efforts to survive that they are basically hyperventilating through each school day. Imagine learning how to ‘determine two or more themes or central ideas of a text and analyze their development over the course of the text’ (a Common Core required standard for reading literature at the 11th grade) when the night before you held your cousin in your arms as he bled to death. This is not a made-up example. It happened to a student in my 5th period last year.”

According to the American Psychological Association’s 2014 Stress in America survey, nearly one in three teenagers reported stress that drove them to sadness or depression, and that their single biggest source of stress was school. It is not unusual for kids to attend a seven-hour school day and then have to do hours of homework, not to mention sports practice, band rehearsals, weekend events and assignments. Studies show that nearly 70 percent of U.S. adolescents do not get enough sleep and that adolescents with sleep problems are more reactive to stress, which can contribute to academic, behavioral and health issues.

Nearly one in three teenagers reported stress that drove them to sadness or depression, and that their single biggest source of stress was school.

The 2018 Stress in America survey indicates that for Generation Z students (those between the ages of 15 and 22 in the year 2019), concern about the state of the nation and high profile issues such as gun violence, sexual harassment, and family separations are also significant sources of stress.

Much of the performance pressure that stresses young people today is the direct result of a culture, both in and out of school, that fails to recognize and encourage the value of real learning over grades and scores. We’ve developed a distorting “consumerist” view of learning. Education historian Diane Ravitch considers this related to the push toward privatization of schooling. “The privatizers hope to establish a free market for schooling where people think of themselves as consumers, not as citizens who have an obligation to educate all the children in their community.”

“The privatizers hope to establish a free market for schooling where people think of themselves as consumers, not as citizens who have an obligation to educate all the children in their community.”

This viewpoint leads to many children being denied access to a good education. It exacerbates the stress that is degrading the physical health and well-being of our students. It also undermines our very sense of what’s right and wrong. An over emphasis on high-stakes test scores led entire school systems to “coordinated, district-wide, centrally orchestrated cheating.” Whole industries have grown up around “contract cheating:” wealthy parents were indicted for paying a consultant millions of dollars to secure their children’s admission to top schools by fraudulent means, including falsification of test scores and bribery of school officials. A growing online business of “essay mills,” sadly propelled in part by former teachers, encourages high school and college students to “buy” ghost-written papers they turn in as their own work.

Raising the stakes for students are studies suggesting that certain features of college admission essays may be predictive of college grades, leading some researchers to suggest that these essays be used in college admission decisions. Sadly, instead of using this data as motivation to learn better thinking and writing skills, students may well be encouraged to simply buy a “winning” essay – cheating not only the college, but their own learning.

As disturbing as these examples are, even more worrisome is the way participants rationalize their behavior. In a radio interview about the practice of turning in purchased essays, one student said, “Technically, I don’t think it’s cheating because, like, you’re paying someone to write an essay, which they don’t plagiarize, but they write everything on their own.” The interviewer asked, even if the writer wasn’t guilty of plagiarism, wasn’t she? “That’s just kind of a difficult question to answer. I don’t know how to feel about it. It’s kind of like a gray area.” A teacher-writer interviewed said “These kids are so time-poor, and I don’t necessarily think that being able to create an essay is going to be a defining factor in a very long career. I actually applaud students that look for options to get the job done and get it done well.”

Aside from defining out and out fraud as a “virtue,” all of these attitudes miss the whole point and purpose of education and learning. To lead healthy, fulfilling lives, young people need to have a sense of agency for their own learning. That is, they need to be motivated and take initiative, either because they understand they need to learn to meet their goals, not just fulfill a requirement; or because they have a love of learning for its own sake, based on their own personal experience of the strength and satisfaction it brings. In either case, they need to see learning as a process they must go through, something of value they can’t just “buy.”

The natural drive to learn is something we are all born with. Nurturing it is essential to our human fulfillment, yet so easily undermined by our culture, including schools and even families. One factor is the over reliance of our education system on core standards and high-stakes testing, which reinforces both unhealthy student stress and the pressure to “cut corners.” What’s needed is a system that encourages students to make progress toward fulfilling their own potential — a system that triggers the powerful adolescent sense of reward for real learning.

What Works: Deep, Challenging and Relevant School Experience

An increasingly popular and effective classroom approach for students of all backgrounds is “project-based” learning in which students explore real-world problems and challenges. Students select their own “open-ended” projects and, along the way, gain knowledge and skills in a variety of subjects. By working as a group, they learn collaboration and the ability to question and articulate their findings. In the process, they learn what they need to pass tests, but in a way that makes sense so the knowledge is retained.

“The more you work as a teenager, the more likely you are to work five years from now. That’s true at the state or national level. When young people don’t get work experience, it inhibits their wages.”

Education professor Yong Zhao takes it a step further, advocating for “product-oriented learning” – as an outcome of the project, students produce a product they can market or otherwise share with the outside world. Curriculum designed to include collaboration and interaction with local industries is also helpful, enabling young learners to experience and appreciate the relevance of what they learn in a real work situation, and to make connections with people in the community who may become their mentors, future employers and associates.

Early work experience also helps teens and young adults build confidence and pick up crucial practices, like getting to work on time and knowing how to relate to one’s boss. According to Andrew Sum’s research for the Brookings Institution, “The more you work as a teenager, the more likely you are to work five years from now. That’s true at the state or national level. When young people don’t get work experience, it inhibits their wages.”

What Works: Tutoring, Mentoring, and Jobs

David Kirp describes what he called a tutoring-on-steroids program in Chicago Public Schools: “After just a single year…participants ended up as much as two years ahead of students in a control group who didn’t get this help…they performed substantially better on the Chicago school system’s math test; their scores on the N.A.E.P. math exam reduced the usual black-white test score gap by a third. This success carried over to non-math classes, where these students were less likely to fail. Greater success in math also helped get them on track to graduate. It also led them to become more engaged in school, and they were 60 percent less likely than members of the control group to be arrested for a violent crime. He quotes the program’s director: “‘It’s friendship and pushing — they nag them to success. These students can make remarkable progress when they appreciate that their tutor is in their corner. The math connection leads to better study skills and a love of learning. Grades improve across the board.’”

Kirp also wrote about the success of YouthBuild programs in multiple cities for 16- to 24-year-olds, many of whom are poor, have a criminal record, or have kids of their own. The most poignant point he makes is that teachers and counselors are available with important supports that are much easier for more affluent parents to provide: going with them to court, helping with college applications, or helping them obtain a driver’s license. YouthBuild combines academics with on the job training, so students can see the relevance of what they learn. The program also provides opportunities for kids to give back: for example, for a small stipend, some build or repair homes for poor or homeless people.

One young man told Kirp, “In high school, no one gave a damn, but here, they really care about you. They have your back.” YouthBuild founder Dorothy Stoneman told Kirp that kids who have “reached a dead end” are offered “a community that helps them find their purpose.” The result: 70% earn a high school diploma, GED or other industry recognized credential; 61% are placed in jobs and postsecondary education; 1-year recidivism for those who were in prison is under 10%, well below the national average.

In the summer of 2018, New York City’s Summer Youth Employment Program provided six weeks of work for almost 75,000 young people ages 14- to 24. The program helps keep many kids out of trouble, which may well save their lives. It also improves academic standards, especially for those most badly in need of help.

San Diego based Real World Scholars takes the approach of “dissolving the walls between school and community” as a catalyst for learning. Real World’s EdCorps project provides a platform that allows any classroom, kindergarten through high school, to “explore entrepreneurship and operate as a business…We take care of the scary stuff—banking, taxes, and start-up funds—so students can engage in a real world entrepreneurial process that allows them to ship their ideas and talents into the world while engaging in work that matters.” Real World’s EdHarmony project focuses on connecting students with local businesses and community organizations “to build meaningful relationships and add their brilliance to the collective genius helping communities thrive.”

The Young People’s Project (YPP) developed as graduates of the Algebra Project looked for a way to give back as they moved into college, graduate school, and the work world. YPP now runs math literacy training programs that train high school and college students as math tutors, as well as a program to train the trainers, with “the essential goal that participants will leave the training with a deeper sense of the way in which their personal and collective gifts can be used to enhance learning for others and improve the quality of public education for all youth.” To date, YPP has trained more than 5,000 teens and college students across 10 states, facilitating more than 10,000 hours of math literacy workshops for elementary students. YPP chapters across the country join local organizing networks and coalitions such as Boston United for Students, Teens Lead the Way Civics Campaign, Massachusetts Coalition to end the Cradle to Prison Pipeline, and the Youth Jobs Coalition. YPP also runs local and national tournaments in Flagway, a game that combines speed, athleticism, and precision with the mastery of mathematics, all with the same elements as most sports: running, scoring points, teamwork, coaching, training, competition, collaboration, and fun.

We need to invest in expanding programs and educational approaches like these that help all young people pave their way to a successful, independent future.

Improbable Scholars

The Rebirth of a Great American School System and a Strategy for America’s Schools

David L. Kirp

How do we determine if our schools are preparing students for a meaningful future in our society and improve the schools that are not living up to those standards? Explores the current crisis in American education and four districts that have made positive changes.

One World Schoolhouse

Education Reimagined

Salman Kahn

There may be a young girl in an African village with the potential to find a cancer cure. A fisherman’s son in New Guinea might have incredible insight into the health of the oceans. By combining the enlightened use of technology with the best teaching practices, we can foster students who are capable of self-directed learning, deep understanding of fundamentals, and creative approaches to real-world problems.

Beyond the Hole in the Wall

Discover the Power of Self-Organized Learning

Sugata Mitra

Sugata Mitra’s now famous experiments have shone light on the immense capacities that children have for learning in self-composed and self-regulated groups.

In the series: Challenges and Opportunities

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

To Improve Teaching, Ask the Kids

Denisa R. Superville, Education Week

In a professional development session aimed at making lesson plans more relevant and engaging, this Des Moines high school included face-to-face interviews with nearly 100 students. Their advice was frank.

High School Doesn’t Have to Be Boring

Jal Mehta and Sarah Fine, New York Times

Debate, drama and other extracurricular activities engage students in the way most regular classes do not. How can we make what happens before the bell more like what happens after it?

Watch: The mysterious workings of the adolescent brain

Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, TED

Why do teenagers seem so much more impulsive, so much less self-aware than grown-ups? Cognitive neuroscientist Sarah-Jayne Blakemore compares the prefrontal cortex in adolescents to that of adults, to show us how typically “teenage” behavior is caused by the growing and developing brain.

Watch: Project-Based Learning: An Overview

Edutopia

Project-based learning is a dynamic approach to teaching in which students explore real-world problems and challenges.

Return to the Teenage Brain

Richard A. Fiedman, New York Times

What if we could turn back the clock in the brain and recapture its adolescent plasticity? This possibility is the focus of research in animals and humans.

Age of Opportunity: Lessons from The New Science of Adolescence

Lessons from The New Science of Adolescence

Laurence Steinberg

A leading expert offers advice for raising happy, successful kids by helping them achieve the self-control they need to navigate the challenging, but developmentally crucial adolescent years.

All About Me

Hoopoe Books

Based on the latest psychological research, this series of books is designed to help adolescents navigate a time when, as it were, their brain is “open during remodeling:” what’s going on with what they see, think, and feel, how their new abilities work, how they change, grow or get stuck—and how reliable they are as they try to make sense of themselves, friends and relatives, and the world around them.

Me and My Feelings

Me and My Memory

What’s the Catch

What We See and Don’t See