Greece:

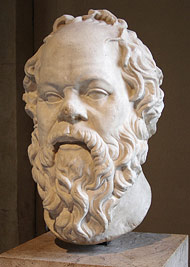

Socrates (470–399 BCE)

Socrates, the founder of Western philosophy, did not document his teachings. All that is known about him comes from the accounts of others: mainly the philosopher Plato and the historian Xenophon, who were both his pupils.

Karl Jaspers writes in The Great Philosophers, Vol. 1, “His mission was only to search in the company of men, himself a man among men. To question unrelentingly, to expose every hiding place. To demand no faith in anything or in himself, but to demand thought, questioning, testing and so refer man to his own self. But since man’s self resides solely in the knowledge of the true and the good, only the man who takes such thinking seriously, who is determined to be guided by the truth, is truly himself.”

The objectives of this rigorous, lengthy and relentless dialogue were to demonstrate the limits of a student’s … ability to arrive at real knowledge in this manner, and to expose the student’s assumptions….

“Let it be clear to you that my relationship to philosophy is a spiritual one,” Socrates says at his trial. His teaching method, known as elenchus (cross-examination), is often thought to be designed to draw out the pupil’s innate knowledge through a series of meticulous, rational questions and answers. This describes the process. but its purpose was more than a search for innate knowledge as we generally understand it. It is more likely that the objectives of this rigorous, lengthy and relentless dialogue were to demonstrate the limits of a student’s—or anyone’s—ability to arrive at real knowledge in this manner, and to expose the student’s assumptions, opinions and false beliefs in order that that he or she might eventually realize that there was no right answer. Through this confusion the individual would see that he or she really knew nothing at all, at which point the search for truth could begin. Finally, by questioning their most fundamental assumptions, and through unrelenting questions and answers, individuals would be able to access an intuitive ability—a change in consciousness—and perceive ultimate good.

In Theaetetus, Socrates describes himself as a midwife, guiding each student to discover within himself a level of intuitive understanding and self-knowledge that was synonymous with virtue.

In 399 BCE, Socrates was accused of two violations of Athenian law: blasphemy by teaching about new gods not recognized by the Athenians, and corrupting the youth of Athens.

Like Pythagoras, the Buddha, and many other teachers, Socrates wrote nothing down, resisted formulating a coherent philosophical path and had no dogma. He was aware that some students, at least initially, were merely entertained by practicing his method, but he knew otherwise: “They enjoy hearing men cross-examined who think they are wise but they are not. But I maintain that I have been commanded by the God to do this through oracles, through dreams, and in every way in which some divine influence or other has ever commanded man to do anything,” writes Plato in The Apology.

In 399 BCE Socrates was accused of two violations of Athenian law: blasphemy by teaching about new gods not recognized by the Athenians, and corrupting the youth of Athens. He was accused of teaching young men idleness and encouraging cultish behavior. But perhaps above all—when the great Athenian Empire was losing to the Spartans towards the end of the Peloponnesian War—he was, in a sense, a scapegoat for their shame, disliked because he numbered among his friends and students men who were perceived as enemies of the Athenian State, such as Alcibiades and Critias. (Alcibiades had, on several occasions, changed sides, and Critias became part of the pro-Spartan oligarchy installed after Athens lost the war in 404 BCE.) In addition, his dialectic method—whereby through rigorous questioning he led people to see the fallacy and limits of their thinking—made many conclude that he was merely intent on making them feel inferior.

Even in defending himself at his trial, Socrates revealed that first and foremost he was a teacher. “I shall never cease from the practice of philosophy, exhorting anyone whom I meet and saying to him after my manner: You, my friend … are you not ashamed … to care so little about wisdom and truth and the greatest improvement of the soul, which you never regard or heed at all?” Instead of offering a defense that would assure his release, he refused to compromise and used the opportunity to expose the shallow, emotionally driven thinking of the members of the judiciary: “For if you kill me, you will not easily find another like me, who, if I may use such a ludicrous figure of speech, am a sort of gadfly, given to the city by God … [But] you may feel out of temper like a person suddenly awakened from sleep and might suddenly strike me dead … and then sleep on for the remainder of your lives, unless God in his care for you sends someone to take my place.”

When the possibility of escaping from jail was presented to him, Socrates used this as an opportunity to teach Crito to observe the effect and consider the consequences of one’s actions, thoughts and feelings. In this instance such an action would in a sense destroy the Athenian state, whose laws had permitted his birth, upbringing and education and of which he willingly chose to be a citizen, obedient, therefore, to its laws. Socrates, in a lengthy dialogue, takes the part of the state and determines that if he did not stand by this agreement now, he would be dishonored, and his friends suffer by association.

“[Man] has only one thing to consider in performing any action—that is, whether he is acting rightly or wrongly…”

Socrates had no fear of death: “You are mistaken, my friend, if you think that a man who is worth anything ought to spend his time weighing up the prospects of life and death. He has only one thing to consider in performing any action – that is, whether he is acting rightly or wrongly… . No one knows with regard to death whether it is not really the greatest blessing that can happen to man, but people dread it as though they were certain that it is the greatest evil, and this ignorance, which thinks that it knows what it does not, must surely be ignorance most culpable.”

So he drank the hemlock and was put to death as the State required. “Such, Echecrates, was the end of our friend, who was, we may fairly say, of all those whom we knew in our time, the bravest and also the wisest and most upright man,” says Crito at the end of Phaedo.

Xenophon

He was a student of Socrates and would later record a number of Socratic dialogues as well as personal accounts of Socrates, whom he admired greatly. His prose included not only histories, but biographies, political pamphlets, and instruction manuals on an array of subjects, including household management, hunting and military tactics. He is often called the original “horse whisperer,” having advocated sympathetic horsemanship in his treatise “On Horsemanship.”

Plato (428–347 BCE)

The most important thinker to follow Socrates was his pupil Plato.

He was an aristocrat, his mother was descended from Solon and his father from the last king of Athens, Codrus. Unlike his mentor Socrates, Plato was a prolific writer as well as a teacher. A devoted pupil of Socrates, three of his early dialogues—The Apology, Crito, and Euthyphron—plus the later Phaedo are devoted to the trial, prison days, and ultimate death of his teacher.

After the death of Socrates, Plato, disillusioned with political life, traveled in Egypt and Italy for approximately ten years. He made contact with the followers of Pythagoras, whose understanding that numbers and geometric forms provided a way in which to understand reality, stimulated his own Theory of Ideas (of Forms).

In 387 BCE, Plato founded the Academy in Athens which lasted in one form or another for nine hundred years until 527 AD. Plato and other teachers instructed students from all over the Greek world in metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, politics, natural and mathematical sciences. Although the Academy was not meant to prepare students for any sort of profession, members of the Academy were invited by various cities to aid in the development of their new constitutions.

Around 390 BCE, Plato is thought to have written The Republic. He did this in part to challenge the prevailing attitudes of the Sophists, the hired teachers that instructed the sons of Athens at this time, who were teaching a subjective morality that went something like this: whatever is to one’s advantage should be engaged in, and whatever is not, should be avoided. They considered any other morality a mere convention, insisting that the strong have advantage over the weak, and concepts of objective justice or objective truth were merely the products of propaganda and the tools of oppressors.

Perhaps the most famous extract from Plato’s work is in Book VII of The Republic, where he describes his ideas in the form of an allegory. In a dialogue between Socrates and a student named Glaucon, The Allegory of the Cave provides a poignant image of human beings who, although ignorant of their condition, are, since childhood, imprisoned in a cave, chained and able only to face straight ahead. Unable to move, in that position they can see only the shadows of what is behind them reflected on the cave walls in front and can hear only echoes of real voices. Knowing nothing else, these shadows and echoes seem to them to be real, as appearances are real to us.

Towards the end of the allegory, Plato refers to the demise of his old master when, as Socrates, he asks us to consider what it might be like if someone who had seen reality came back down into the cave. What, he asks, would the people think of him? He would inevitably be misunderstood and would become a laughing stock. If, in addition, he tried to set the captive men free and take them to the light, “if they could somehow get their hands on him and kill him, wouldn’t they do just that?” Glaucon agrees that they would.

The world revealed by our senses is not the real world but only a poor copy of it.

Then Plato, as Socrates, further reveals the meaning of this allegory and his own philosophical understanding: “That is the picture then my dear Glaucon, and it fits what we were talking about earlier in its entirety. The region revealed to us by sight is the prison dwelling and the light of the fire inside the dwelling is the power of the sun. If you identify the upward path and the view of things above with the ascent of the soul to the realm of understanding, then you will have caught my drift, my surmise, which is what you wanted to hear. Whether it is really true, perhaps only God knows. My own view, for what it is worth, is that in the realm of what can be known the thing seen last and seen with great difficulty is the form, or character of the good. But when it is seen, the conclusion must be that it turns out to be the cause of all that is right and good for everything. In the realm of sight it produces light and light’s sovereign, the sun, while in the realm of thought it is itself sovereign producing truth and reason unassisted. I further believe that anyone who’s going to act wisely either in private life or in public life must have had a sight of this form of the good.”

The world revealed by our senses is not the real world but only a poor copy of it. The real world can only be apprehended through the effort of rational thought. Justice was rational and people needed to be brought up in a society governed by reason. Enlightened individuals, in Plato’s view, had an obligation to the rest of society to serve it. Society in order to be good should be ruled by them—the truly wise Philosopher-Kings.

[Plato] argued that all conventional political systems were inherently corrupt, and therefore the state ought to be governed by an elite class of educated philosopher-rulers…

Plato says in The Laws, “We should keep our seriousness for serious things and not waste it on trifles, and … while God is the real goal of all beneficent serious endeavor, man … has been constructed as a toy for God, and this is, in fact the finest thing about him. All of us, then, men and women alike, must fall in with our role and spend life in making our play as perfect as possible.”

Axial Age Greece was approaching its end, and, unlike the teachings of typical Axial teachers, Plato’s utopian city was elitist and lacked compassion. He argued that all conventional political systems were inherently corrupt, and therefore the state ought to be governed by an elite class of educated philosopher-rulers, who would be trained from birth and selected on the basis of aptitude.

Always seeking a practical application of his ideals, he identified justice as presiding in the structure of this ideal city where its functions are implemented through specialization: everyone does what he is best fitted to do and you have a just city. Similarly in the individual—in a just soul, there is a correct balance between the parts: the rational part must rule and dictate the overall aims of the human being, the emotional part must enforce the rational part’s convictions, and the appetitive part must obey.

Plato claimed that since our experiences were unreal compared with the world of the Forms, people should devote themselves to understanding the reality of the Forms which they could do if they applied themselves, through discipline and rational thought. He disapproved of poetry, music and theater, which were part of traditional Greek education, because these things aroused irrational emotions and encouraged people to give in to them; they encouraged immoderation and sympathy, both of which were incompatible with virtue in Plato’s view. Life was sometimes miserable, but it was not real, and it was only possible to ascend to the real world through self-controlled, disciplined and rational behavior.

Karen Armstrong says in The Great Transformation, “At the beginning of his philosophical quest, Plato had been horrified by the execution of Socrates, who had been put to death for teaching false religious ideas. At the end of his life, he advocated the death penalty for those who did not share his view. Plato’s vision had soured. It had become coercive, intolerant, and punitive. He sought to impose virtue from without, distrusted the compassionate impulse, and made his philosophical religion wholly intellectual. The Axial Age in Greece would make marvelous contributions to mathematics, dialectics, medicine, and science, but it was moving away from Spirituality.”

Plato’s Academy would eventually become the model for the Western university.