Neolithic Era:

Beliefs and Customs Journey West

Kamel15, Wikimedia Commons

As land became exhausted, people were obliged to move to newer pastures. Now they could travel not only with their families but taking their animals, and, most importantly for us, their customs and beliefs with them.

Some moved westwards, settling in what we now know as Europe, around the Danube; others went southwest to Italy and surrounding areas. About 4500 BCE they arrived in Brittany, western Portugal, and Holland.

They reached Britain and Ireland about 500 years later. Some travelled from Brittany to the coasts of Ireland and Wales; others crossing the channel arrived on the shores of England. These farmers brought the agricultural revolution with them to Britain, cultivating cereal crops and raising livestock. They would eventually replace the indigenous hunter-gatherer people entirely. Some 40 generations later, their descendants would build the first Stonehenge.

The many megaliths help us trace their voyage westwards from Anatolia. Like Göbekli Tepe and other earlier sites, these were created not for domestic but for religious purposes. These gigantic structures are thought to be predominantly burial places, perhaps for the most celebrated members of a family or farming community.

Farmers now needed to own the land they worked. The large structures at burial places not only honored their ancestors but established their presence by indicating: “this land is ours, our ancestors are here too, and we will protect it.” The dead were now regularly buried along with the everyday things they had used in life, ornaments, weapons, pottery, that presumably might be needed in the next world.

Almost 5,000 years after Göbekli Tepe was abandoned and 3,000 years after Çatalhöyük’s demise, the actions that would solve the main problems we faced once we left the caves were now systematic and ritualized. The problems were the same: how long would life as we know it last? And how do we maintain it? The idea of a tiered cosmos held fast, and it seems certain that in the minds of our ancestors, communication with the spirit world was still the only way to solve these problems.

The shaman’s role was perhaps more complex now. Communities were much larger, and people spent more time outside where the vast horizon and immense heaven may well have made these other worlds seem much more distant. But the early priesthood was up to the task: the spirits became gods, these gods required worship, ritual and sacrifice from the whole community. Huge structures had to be created to contact them. Continuity here was dependent upon continuity with the ancestors who, buried under these structures, were most likely intermediaries to the gods. Only through the expenditure of enormous effort by hundreds of people, both the living and the dead, could these gods be reached.

These ritual leaders needed to maintain control. Able to achieve altered states of consciousness and travel to these other worlds, they now began to modify aspects of their route in order to share them with the community at large. Drums and chanting, echoes, light and dark would now be used in organized ritual, and the Neolithic Scientific Revolution began.

Gavrinis and Newgrange: Cultural Diffusion

On the small uninhabited island of Gavrinis off the coast of Brittany is a stone burial chamber built around 3500 BCE. It appears to be an earth mound with a diameter of 164 feet (50 meters) which covers a cairn or stone mound which itself covers a burial chamber. To reach the chamber one must walk down a low, narrow 46-foot–long passage whose walls are decorated with carved symbols, such as axe heads, horned animals, swirls, snake-like patterns and spirals. The burial chamber is covered by a 17-ton stone slab and is also decorated with drawings, including one of a bull.

Similar to Gavrinis, but a very much larger passage tomb, is Newgrange in County Meath, Ireland. Constructed between 3300 and 2900 BCE, scholars estimate it took a workforce of 300 people about 20 years to complete.

These spots were not just burial places, monuments or temples for the dead. They were structured to harness the sun at the time most important to these early peoples: the winter solstice, when through supplication and ritual they and their ancestors would honor the god, who in turn would return to revive the world after the long, dark winter. At Newgrange on December 21, a transom opening above the entrance lets in the rising sun and beams of light illuminate the entire passageway straight down into the heart of the mound to an artificial cave, the corbelled roofed chamber where the burned bones of the ancestor were placed.

External Stories and Videos

Watch: Göbekli Tepe

BBC

How did the first farmers sustain a large community and build Göbekli Tepe 12,000 years ago?

History of Stonehenge

English Heritage

Explore the history of this prehistoric monument with interactive maps of all phases of development.

Watch: Secrets of Stonehenge

National Geographic

Many secrets remain surrounding the creation of Stonehenge. Archaeologists try to unravel the mystery.

Unveiling an Underground Prehistoric Cemetery

Google Arts and Culture

A look inside Malta’s World Heritage Site, the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum.

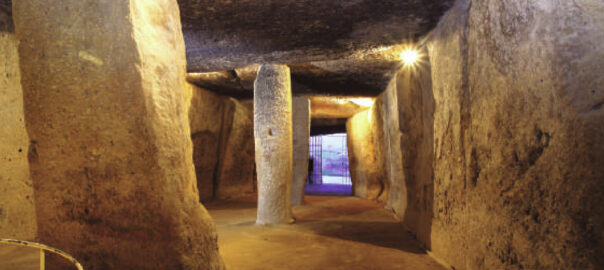

Early science and colossal stone engineering in Menga, a Neolithic dolmen (Antequera, Spain)

The earliest megalithic chambers in Europe appeared in France in the fifth millennium BCE. Menga is the oldest of the great dolmens in Iberia (approximately 3800 to 3600 BCE). Menga’s capstone #5 weighing 150 tons is the largest stone ever moved in Iberia as part of the megalithic phenomenon and one of the largest in Europe.