Neolithic Era:

Cosmic and Terrestrial Maintenance

Gobekli Tepe. Kerimbesler, Wikimedia Commons

As the climate warmed, food sources became more plentiful, and population numbers grew. An enormous communal effort and new inventions were required to assist and impress the spirit world to maintain cosmic and terrestrial harmony and prevent a return of the perilous Ice Age. This effort shaped the Neolithic Revolution—the beginnings of organized religion, agriculture, and science. It created the first divine beings or gods and the many pre-Axial religious beliefs, and rituals associated with them, traces of which are evident to this day.

Imagine how different the Neolithic world would seem from the stories told and passed on by the elders of life in the Ice Age. With a terrain rich in wild grasses and game, it was now often pleasant to leave cave and rock shelters and gather outside, to sit and look across grasslands where animals grazed in their thousands, or to gaze up to the luminous night sky. In this land of plenty, the relatively easy life of the forager became possible. But how long would it last? And how do we maintain it?

These became crucial questions. From then on it became important to appease the spirits to prevent a return to the blizzards, snow, ice and food scarcity. Now magic, ritual, and sacrifice were shared among thousands to invoke “Cosmic Maintenance.” An enormous communal effort was required to create new places to meet regularly to perform them.

Then it became necessary to feed the builders, craftsmen, and devotees and to ensure the availability of sacrificial offerings. This in turn gave rise to temporary and permanent settlements near the sacred sites, an advance in symbolic thought and the first gods, organized religion and a managerial religious elite, the domestication of plants and animals, and amazing feats of engineering.

The Neolithic Revolution—the change from hunter-gatherer to farming societies—seems to have happened in different places, in different ways. This is a very short overview of the findings from the Neolithic world in the Near and Middle East. Much remains still to be discovered.

Neolithic Religion: From the Caves to a New Tiered Cosmos

Approximately 11,500 years ago, towards the end of the last Ice Age as the weather became warmer, some of our early ancestors in the northern region of what we now know as the Fertile Crescent began to move their places of religious ritual beyond the cave and rock walls. Göbekli Tepe is the first evidence to date of this transition. This extraordinary man-made place of worship heralds a new period of creative expression we know as the Neolithic (“new stone”) era.

Here, 7,000 years before Stonehenge, our ancestors, using only flint tools, carved massive pillars from a limestone quarry, then transported them as far as a quarter of a mile without the aid of wheels or beasts of burden. The tallest of these pillars are 18–20 feet in height and weigh up to 50 tons.

Each pillar is shaped like a stylized human being, its “head” like a capital “T.” Some have relief carvings on their “bodies” indicating arms, hands, belts and animal skin loincloths; others are decorated with animals then native to the area: bulls, foxes, cranes, lions, ducks, scorpions, ants, spiders, and snakes.

The pillars were erected to form circular or oval shapes ranging from 30 to 100 feet in diameter, each pillar standing an arm span or more apart connected to the next by a stone wall; two larger pillars stand within the center. Scholars feel sure these structures originally supported domed roofs; their semi-sunken pillars are load bearing and, left uncovered, limestone would too easily have been damaged from rain and wind.

These buildings would have been visible from a very long distance away yet there is no sign of habitation, so it seems certain that this was a meeting place used for religious and ceremonial purposes only. From the many animal bones that have been found it seems likely that once pilgrims reached Göbekli Tepe, they made animal sacrifices. More recently, freestanding sculptures of animals have been found within the circles. A statue of a human and sculptures of a vulture’s head and a boar have also been excavated.

It is possible that hunter gatherers, who were now able to gather in larger numbers, erected these initiatory sites to perform multiple ceremonies of birth, initiation to adulthood, burial, ancestor veneration and shamanism; and perhaps also to ensure, through ritual, magic, and sacrifice, the collaboration of the spirit world and of their newly conceived gods of nature: the sun, wind, rain and soil.

A recent study suggests that one of the pillars may contain a record of a comet striking the Earth about 10,950 BCE, an apocalyptic event that may have triggered the sudden “mini” ice age known as the Younger Dryas, leading to great loss of human life and the demise of the woolly mammoth.

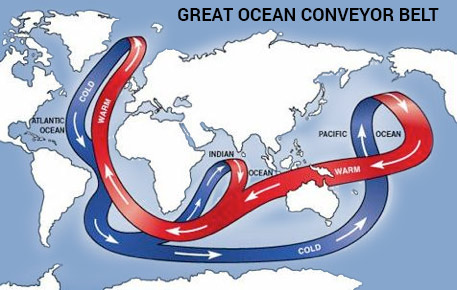

The warm-water currents of the sea’s Great Conveyor Belt shut down. As a result, the Gulf Stream was no longer flowing. Within two or three years the last of the residual heat held in the North Atlantic Ocean dissipated into the air over Europe, leaving no more warmth to moderate the northern latitudes. When the summer stopped in the north, the rains stopped around the equator, so at the same time Europe was plunged into an Ice Age, the Middle East and Africa were ravaged by drought and wind-driven firestorms. This phenomenon is, in fact, a concern today for climate scientists, with fears that the melting of Greenland’s ice cap will very quickly put Europe in a deep freeze.

“It appears Göbekli Tepe was, among other things, an observatory for monitoring the night sky,” explains Martin Sweatman, an author of the study. “One of its pillars seems to have served as a memorial to this devastating event—probably the worst day in history since the end of the ice age.”

A New Organizational Hierarchy

We know, through ground penetrating radar, that there are 20 of these circular enclosures. An estimated 500 people would have been required to move one pillar, and many more to accomplish all the construction and embellishments and attend to the crowds the site attracted. Specialist stoneworkers must have worked the pillars.

In order to accomplish this archaeological feat, an organizational hierarchy would have been imperative. Scholars speculate that an elite class of religious leaders supervised the work and later controlled the rituals that took place at the site. Shamans would still be looked to for guidance and from this already elevated position, they were perhaps able to take control. As community leaders—a priesthood of sorts—they would command the numbers of people needed to initiate this transformation: to create a new tiered cosmos beyond the cave walls.

A New Symbolism and the First Gods

To live within their new large communities, people of the Neolithic world needed to systematize their animistic world with a powerful symbolism that, although it signified abstract and supernatural concepts, was easy to remember and easy to transmit.

Scholars such as the French archaeologist Jacques Cauvin suggest that the massive pillar structures mark a “revolution of symbols”—a “psycho-cultural” change enabling the imagination of a structured cosmos and supernatural world in symbolic form. Perhaps for the first time, human beings imagine gods, supernatural beings resembling humans that exist in the other worlds.

Images were by now probably understood in a more iconographic way, reminding participants of the stories and myths of the time, as a totem might, or as a statue does in a modern church or temple. Sites as far as 100 miles away shared this same imagery and more than likely people shared the same stories and religious ideas associated with it. Smaller but similar pillars with the same imagery, dating just after Göbekli Tepe were found at Nevali Çori, a settlement 20 miles away. Karahan Tepe, almost 40 miles east of Urfa in the Tektek Mountains, is a similar site that has as yet to be explored. Dated c. 9500–9000 BCE, it has a number of T-pillars as well as high reliefs of a winding snake and other carvings similar to those at Göbekli Tepe.

As archeologist Trevor Watkins writes “The great advantage of all this symbolic reference through physical artefacts was that, unlike speech, dance or ritual enactment, which is transient, the physical symbolism with which they surrounded themselves was always there, always reminding them, teaching their children. They had learned what the psychologist Merlin Donald (1991, 1998) has called ‘external symbolic storage’…. Above all, these ideas about their world were systematic, categorical, discriminating, ordered.

“Such a systematic and symbolically rich world-view was ideal for providing the cultural underpinning that could be shared by all those in the community, for they lived in and by and through the symbolic references in their settlements. And finally, such a systematic and readily symbolised world-view was infectious, readily communicated and easily learned by others who had the same cognitive skills and the same need to cope with their new way of living.”

External Stories and Videos

Drought and Drone Reveal ‘Once-in-a-Lifetime’ Signs of Ancient Henge in Ireland

Daniel Victor, New York Times

It took an unusually brutal drought for signs of a 5,000-year-old monument to suddenly appear in an Irish field, as if they had been written into the landscape in invisible ink.

Watch: Göbekli Tepe

BBC

How did the first farmers sustain a large community and build Göbekli Tepe 12,000 years ago?

Göbekli Tepe Stone May Record Comet Collision

Michael Irving, New Atlas

New study suggests temple stone may be a record of an apocalyptic comet collision 12,800 years ago that caused the last ice age.

History of Stonehenge

English Heritage

Explore the history of this prehistoric monument with interactive maps of all phases of development.

How did they do it?

Sarah Knapton, The Telegraph

Just how did prehistoric Britons manage to transport the huge bluestones of Stonehenge some 140 miles from the Preseli Mountains in Wales to their final home on Salisbury Plain? It may have been easier than we thought.

Watch: Secrets of Stonehenge

National Geographic

Many secrets remain surrounding the creation of Stonehenge. Archaeologists try to unravel the mystery.

Unveiling an Underground Prehistoric Cemetery

Google Arts and Culture

A look inside Malta’s World Heritage Site, the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum.