Our Capacity for Social Connection

Connecting with others, and the world around us, has been central to our survival. We evolved to go beyond the individual and transcend the “self”. This universal capacity makes us human and is responsible for our success on the planet.

The content of this section, unless indicated, represents Robert Ornstein’s award-winning Psychology of Evolution Trilogy and Multimind. It is reproduced here by kind permission of the Estate of Robert Ornstein.

Humans evolved with innate abilities that help us live together in diverse groups. From a very early age, babies begin to demonstrate innate cooperative and helpful tendencies, a capacity to tell kindness from cruelty, a rudimentary sense of fairness and justice, and empathy and compassion for others.

We are able to live all over the planet and in all conditions because we can adapt to and change our environment, developing different strategies for survival anywhere on earth; and because we have the ability to understand that different people have different ideas and experiences than ourselves, and we can learn from them and adapt to and with them.

Pivotal to human adaptation is our large brain, which has evolved faster than any other human organ. Its size evolved most rapidly from 800,000 – 200,000 years ago during a time of dramatic climate change, when survival depended upon our ability to interact with others on a wider scale. As the environment became more unpredictable, bigger brains helped our ancestors survive.

As Homo sapiens expanded across Africa, Europe and Asia, natural selection began to favor genes underpinning bonding, cooperation and altruism, with humans realizing they were better off forming cohesive groups that watched out for each other. Two neurochemicals – dopamine and oxytocin influence our emotional attachment and social behavior. They do this in part, by modulating responses in the brain’s amygdala – you’ll remember that these paired structures’ primary role is the processing of emotional responses – and thereby reducing anxiety and fear and enhancing empathy, compassion and social interaction.

While humanity is certainly dominant on Earth now, we forget that our early human ancestors were scrawny and scarce. Living in isolated bands of a few dozen, they needed to bind into communities to help them survive predators and climate fluctuations. It is most probably the case that human beings have thrived as a species because of sophisticated social bonding and attachment to others, which fostered such virtues as forgiveness and gratitude.

Our brain helped us adapt to every kind of geography and climate, and it enables us still today to transcend our biological inheritance. The brain underlies mental life: to learn, to create, to invent, to think and say things no one has ever thought. It is the largest brain, relative to body size, of all land mammals, but the size is not what matters.

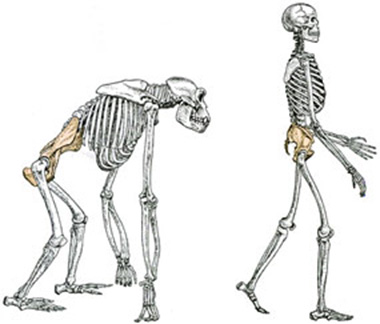

What is crucial is where the brain expanded. Although the anatomy of much of our brain is identical with that of other primates, our cerebral cortex, the uppermost part of the brain, became the largest and most elaborate of all primates. It is responsible for higher brain functions like thought, perception, language, memory, attention, consciousness, and advanced motor functions. Its increase in size gave our ancestors great advantages, none of which would have happened had we not come down from the trees.

Our social brain’s first steps

Bipedal walking and running offered obvious advantages – we could cover greater distances over time than any other animal. A more sophisticated visual system developed along with our upright posture, enabling our ancestors to spot approaching danger or opportunity from farther away.

Hands were freed from weight-bearing responsibilities, making tool use and our modern world possible. But with the freeing of the front limbs, the hind limbs had to adapt to bearing the entire weight of the body. The human back was not originally “designed” to support an upright posture; to support this additional weight, our human pelvis grew thicker than that of the great apes, which made the female’s birth canal, the opening through which infants are born, much smaller.

While the birth canal was becoming smaller, the fetus’s brain and head were growing larger. If there had been no evolutionary correction for this, the human species would have died out; the biological solution was to have human babies born very early in their development.

Human children have the longest infancy in the animal kingdom. Within a day, baby baboons can hold onto their mothers by themselves; but the human child is helpless and will die if not cared for during the first few years of its life. The initial care bonding, usually mother-child, so vital to the infant, is the foundation upon which our connection to each other is based. This social bond extends to the caregiving group: father, relatives, and friends, all of whom provide an environment within which the child’s brain develops. As the proverb says, “it takes a village to raise a child.”

At birth a chimp’s brain is about 45 percent of its adult weight, while a human baby’s brain is 25 percent of its adult weight. This means that 75% of the human brain’s development occurs outside the womb, so our environment, and particularly our social world, play a much greater role in our brains’ development than in any other animal. This has made us exceptionally adaptive and diverse. We are able to survive and even flourish anywhere in the world; we are able to learn from each other, teach each other, and collaborate in uniquely human ways. At the same time, as we have seen, each one of us experiences the world differently and the specific abilities that each of us develops differ considerably.

“Dunbar’s number”

The human brain seems to be equipped for connection to others and has evolved in ways that facilitate this. Recent research has shown that the more personal connections one has — in this case, measured by the size of a person’s social circle — the bigger the brain’s orbital prefrontal cortex. Our “cognitive load,” the mental capacity of managing information, appears to limit our social relationships to about 150 people, a number established by the anthropologist and evolutionary Robin Dunbar and known as “Dunbar’s number.” This is by far the largest social network of any animal, and almost three times larger than that of our nearest hominid relative, the chimpanzee.

Connection to others and perception of a larger whole is the wellspring of humanity’s solidarity in tribes, societies, teams, nations, religions. This universal capacity is responsible for humanity’s success on the planet and is what makes human beings’ lives singular and distinct from the lives of all other animals. While it often doesn’t seem like it — especially these days — almost all of human life is based upon cooperation and connection. Many animals do, of course, show both minor and elaborate cooperation: Wolves and lions do so in the hunt; dolphins work together to chase, corral and scoop up schools of small fry; and ants are legendary in their organization.

But humans are flexible in cooperating in countless pursuits, and with different partners: with a single collaborator, with a few or with many; with a large workgroup, a sports team, a political party or a country. All of these are changeable and flexible connections — which is not the case with other species.

We see the importance of connection clearly in daily life. We become depressed when alone too long; solitary confinement is the most punishing of penalties in incarceration. When we are just sitting at rest, with our brains just idling, it is most often our personal social connections that occupy our minds. The widespread popularity of computerized “social networks” embodies this drive to connect. For many people, the experience of social distancing in response to the Covid-19 pandemic brought this into stark relief.

Human beings evolved to go beyond the individual, to transcend the “self” and to connect in a manner that no other organism can — and this is the basis of our planetary success. Understanding the centrality of “connecting up” yields a different outlook on human nature and on the development of societies. As we shall see in the next section, it reveals the foundation upon which our cognitive ability for higher consciousness is developed.

A sense of what others are thinking and feeling

A look at very young age humans shows how important connection is. Infants have a foundational appreciation of the minds of others. Children as young as fifteen months old can think of the shapes around them as having emotions and wishes and projects that are distinct from their own. We have an innate ability to attribute mental states to ourselves and others which predict and explain behavior. Called theory of mind, this ability means that we can recognize, communicate, and manipulate mental states in others and reflect on our own.

As we know from studying our ape ancestors, other social animals can hunt, mate, nurture their young, recognize others and emotions in others, group together in hierarchies and make alliances—all without this theory of mind ability. But they cannot teach or tease others; they cannot trade with others, nor communicate ideas or complex emotions. Nor can they manipulate beliefs, know what someone else is thinking, or reflect on what they are thinking themselves; and they are not self-aware.

From the beginning of life, babies begin to cultivate this ability: when they are awake and not hungry, they prefer looking at a face and hearing a voice over anything else. At as young as fifteen months children understand false beliefs; from 18 months they exhibit inherent “mentalizing”: they pretend play, understand deception, intention, and implicit or false belief. By the age of five children can explain and predict behavior in others on the basis of their inner state: their intention, desires, beliefs, etc. This mentalizing ability increases our range of social behavior enormously; it allows us to accumulate cultural knowledge and transmit it by teaching. No other animal can do this.

To achieve and expand on our ability to connect with others, our brains became exceptionally adaptive, able and open to responding in multiple ways; the unique success of our human journey is evidence of this. The downside is that we are vulnerable to forces that can be detrimental to our welfare.

Under certain conditions our thinking and behavior can be manipulated. We’ll address many of these in the next section when we discuss morality; but first let’s look at two that, standing alone, leave us all extremely vulnerable in today’s world: the power of Influence and the threat of Stereotyping.

In the series: Connecting with Others

Related articles:

- An Ancient Brain in a Modern World

- Our Unconscious Minds

- Connecting with Others

- Morality’s Long Evolution

- Unconscious Associations

- The Brain’s Latent Capacities

- God 4.0

- Multimind: A New Way of Looking at Human Behavior

- Thinking Big

- Social

- The Righteous Mind

- New World New Mind

- Moral Tribes

- The Mountain People

- The Matter with Things

- Humanity on a Tightrope

- Beyond Culture