Tropical Cyclones in a Warming World

Archie O’Shaughnessy | December 18, 2024

As a marine biology graduate who keeps up with world events, and especially environmental events, I can’t help noticing that hurricanes over the last few years seem to be more frequent and more destructive. For instance, 2020 was regarded as the most active tropical cyclone year on record, with over 100 named hurricanes across the world. Even as this year’s Atlantic storm season ends, the theory that storm frequency is increasing remains debated by scientists. However, it has been generally agreed that the storms we do experience are likely to be more intense.

So, what may be causing this shift in intensity? And why should we better prepare ourselves for potentially more powerful storms in years to come?

First, a quick primer:

Tropical cyclones, also known as hurricanes and typhoons (depending on where you are in the world), are powerful storms that form over oceans and which can cause serious damage to infrastructure and life on land. They form as warm oceans heat the air above, causing it to rise into the lower atmosphere. A low-pressure area then forms, drawing more warm air and evaporated water upwards. This condenses into clouds at a high altitude and gives us the torrential rain that we all associate with hurricanes.

These large storm systems, sometimes spanning up to thousands of kilometers across, begin to circulate due to the spinning of the Earth. If the sea temperature remains high enough and the winds continue to be favorable, the storm will likely continue to grow until it moves over land. Once inland, the hurricane loses its supply of warm, humid ocean air and disbands—but not before causing serious damage to coastal areas.

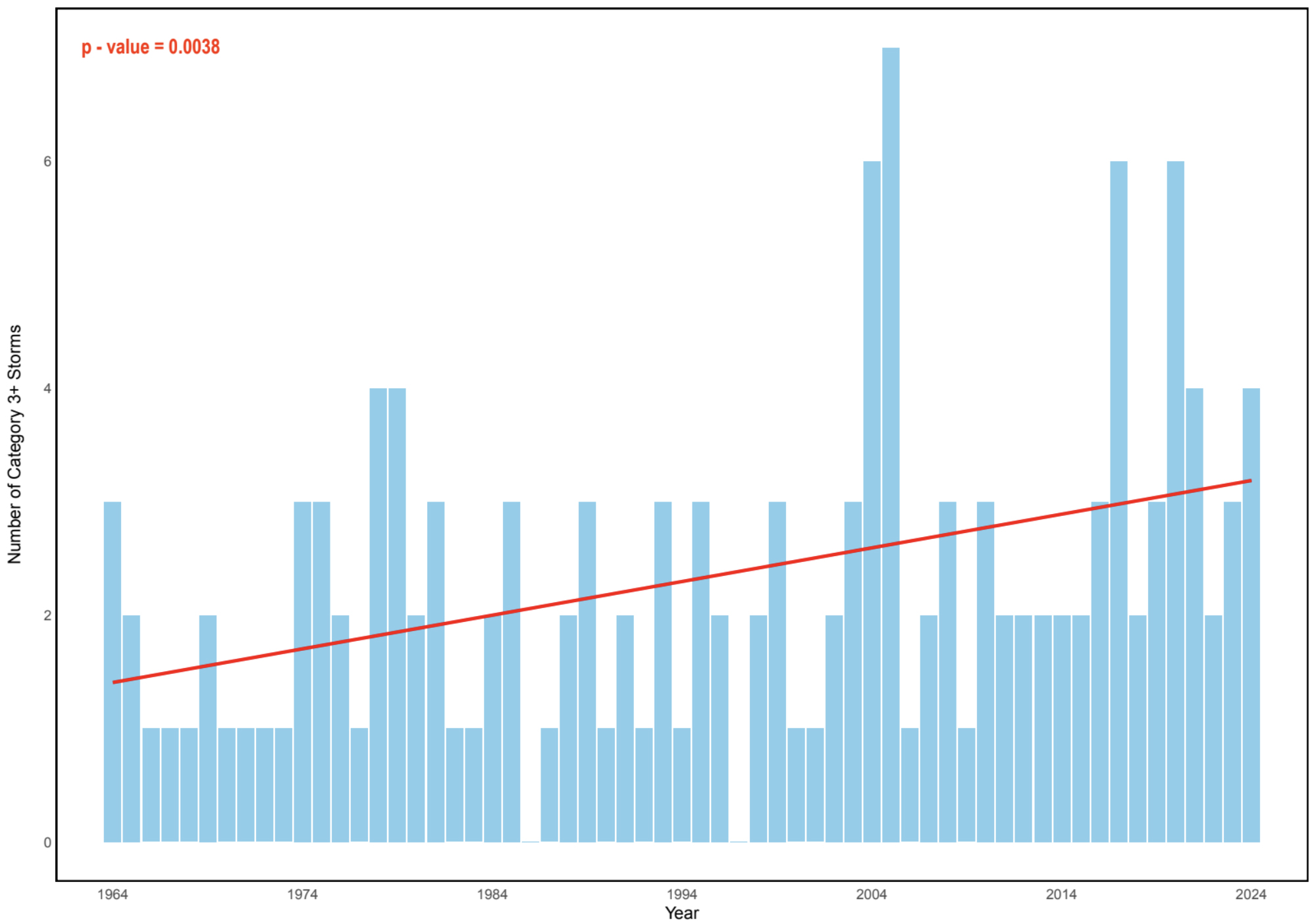

By looking at the number of “major hurricanes” in the North Atlantic (Category 3+) over the last 60 years, we can see that there is a steady increase as time goes on.

Knowing that cyclones begin from warm ocean temperatures, we can logically attribute part of the rise in major hurricanes to global warming. As the Earth warms due to not just the greenhouse effect, but also deforestation and loss of sea ice, the oceans also warm. It has been calculated that with every 1˚C increase in sea surface temperature there is a 12% increase in wind power, and this has been estimated to equate to a 40% increase in destructive potential.

Due to these recognized increases in storm intensities, climatologists have begun to consider modifying the system we use to categorize cyclones—currently based on wind speed and ranging between categories 1 and 5. Some scientists have suggested adding a sixth category to allow for storms that are considerably more powerful than your average Category 5 hurricane.

Whilst this addition of a sixth level seems like a good idea, I feel as though a more advanced system could be more beneficial, especially one that measures wind speed, storm surges and economic damage—and that is similar to the Enhanced Fujita Scale that is used to measure intensity and damage caused by tornadoes in the USA.

One group of scientists has put forward an alternative that they call the “Tropical Cyclone Severity Scale,” taking into account wind speed, precipitation levels, and storm surge severity. A scale like this may better prepare the public for an incoming storm, making them more aware of the less obvious risks, such as flooding. It is essential that we take flooding threats seriously. 76% of hurricane-related deaths in the United States are caused by storm surges and flooding, whilst gale-force winds account for only 8%. Damage to housing and infrastructure is driven as much by flooding as by powerful winds, highlighting the critical need to address both threats in storm preparation. A hybrid categorization system will better inform the public and allow people to take adequate measures, as often lower-categorized tropical storms are not seen to be as dangerous as major hurricanes.

Whatever the case, it is time for a new and more detailed scaling system for cyclones and hurricanes. Given that the warming of our planet is not expected to stop anytime soon, we must prepare as best we can to mitigate the devastating consequences that these “super-storms” will continue to deliver.

For those interested in getting into the nuts and bolts of the matter, I’ve written a longer and more detailed piece on this subject, called “Are We in the Age of Category 6 Hurricanes?”

Archie O’Shaughnessy holds a degree in marine biology and has worked with various endangered species around the world. He is also involved with Hoopoe Share Literacy Fund (HSLF), which is dedicated to translating and distributing his grandfather’s children’s books to kids around the world living in difficult situations.