Featured Book

She Has Her Mother’s Laugh

The Powers, Perversions and Potential of Heredity

Our understanding of heredity has come a long way and holds much promise, but we’ll need wise judgement to manage the emerging science of genetic engineering.

In this wide-ranging and extensively researched book, science writer Carl Zimmer takes an up-close-and-personal look at the phenomenon of heredity, our understanding of how it works and the potential of that understanding to improve our lives. The result is an eye-opening treatment of a complex and nuanced topic that’s fundamental to the question of who we are and how we got that way.

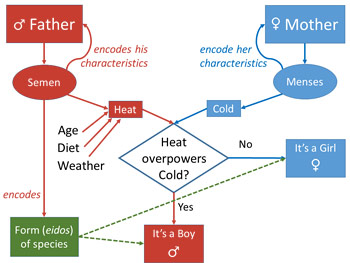

Zimmer’s account of the evolution of human beliefs about heredity is not only interesting in and of itself, but also a vivid illustration of how scientific knowledge typically advances – with each new discovery providing another piece of a puzzle that often continues expanding in scope long after the subject under investigation is considered “solved.” More than two thousand years ago, the Greek philosopher Aristotle contended that procreation was caused by the male’s semen triggering a transformation of fluids inside the female, with organs curdling into existence in an unfolding sequence. He believed that men were the true biological parents because they alone produced the seeds of life, which were nourished inside women’s bodies by menstrual blood – whose influence on children’s traits was similar to that of the surrounding soil on a plant’s development. While the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates was perhaps more egalitarian in holding that both men and women produced semen that mixed and formed new life, he and his contemporaries were still largely in the dark as to heredity’s mechanism – with many ancient Greeks and Romans believing that acquired traits, such as having lost a finger, were passed on to one’s offspring.

Greeks and Romans believing that acquired traits, such as having lost a finger, were passed on to one’s offspring.

As recently as the 1500s, Europeans relied mainly on such theories to explain how characteristics were passed from parents to children. Over the next few centuries, people came to believe that one’s ancestry was carried in the blood (from which we get the expression that the aristocracy are “of noble blood”). In the 1600s, British physician William Harvey theorized that animals grew from eggs, and not long afterwards, the newly invented microscope enabled Dutch naturalist Nicolaas Hartsoeker to discover sperm, which he believed contained tiny humans. But it wasn’t until the 1800s that someone – specifically, German biologist Rudolf Virchow – realized that every cell comes from another cell, from which its traits are inherited. By then, genealogy had become a full-blown industry in the United States, with people vying to prove that they were related to admired public figures and thus partook of the same inherent virtues. For example, Zimmer recounts that one of the early US senators, John Randolph of Virginia, claimed he was a direct descendant of Pocahontas and boastfully traced his lineage back to William the Conqueror.

In the series: Discovering Our Distant Ancestors

- Genetics and Human Evolution

- Our Nearest Relatives: Bonobos and Chimpanzees

- Our Hominid Predecessors

- Neanderthal Man – In Search of Lost Genomes

- The Evolution of Human Morality: The Age of Empathy and The Bonobo and the Atheist

- The Gap: The Science of What Separates Us from Other Animals

- Before the Dawn: New details of human evolution revealed

Further Reading »

Further Reading

External Stories and Videos

Gonads: X & Y

WNYC Studios, Radiolab

A lot of us understand biological sex with a pretty fateful underpinning: if you’re born with XX chromosomes, you’re female; if you’re born with XY chromosomes, you’re male. But it turns out, our relationship to the opposite sex is more complicated than we think.

The Naked Truth

Nina G. Jablonski, Scientific American

Our nearly hairless skin was a key factor in the emergence of other human traits.