Self-Managing Chronic Disease

Four out of five people over the age of 65 have one or more chronic conditions. Chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, and chronic lung disease account for 90% of all illness, 80% of all deaths, and 70% of all healthcare dollars.

Patients can learn from other patients. They can develop the ability to care for oneself through awareness, self-control, and self-reliance in order to achieve, maintain, or promote optimal health and well-being. Consider the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program developed at the Stanford Patient Education Research Center and now disseminated internationally. The educational groups are comprised of patients with one or more chronic diseases such as heart disease, lung disease, stroke and arthritis. The intervention consists of a patient self-management handbook and seven weekly two-hour small group sessions led by lay leaders most of whom themselves have chronic conditions. The focus of the group sessions is not on the specific diseases or conditions. Rather, it is on the shared determinants of functioning and living well with a chronic condition. The program content concentrates on patients’ perceived needs and self-management options for common problems and symptoms such as pain, fatigue, sleeping problems, anger and depression which cut across specific diagnoses. Patients learn skills to maximize their functioning and ability to carry out normal daily activities. Relaxation and imagery are taught and practiced within the group sessions. They also learn how to manage the emotional changes brought about by illness such as anger, depression, uncertainty about the future, changed expectations and goals, and isolation.

Those participating in the course . . . had fewer days in the hospital and visits to emergency departments resulting in reduced healthcare costs per person in the range of $400 to $1000 per year. This equates to a potential net national savings of $3.3 billion if only 5% of adults with one or more chronic conditions are reached with this type of self-management education and support.

A significant part of learning and benefit comes from being able to share and help other patients, which reduces a sense of isolation and shifts the focus from one’s own problems to helping others. Even patients with high levels of social support may feel isolated within their life role as a person with a chronic disease. The group interaction also improves the participant’s sense of their own capabilities by putting their disabilities in perspective through the process of social comparison: “Things could be worse, I could have…”. They develop a greater appreciation of what they can do, what’s working right or improving, rather than focusing on their limitations and disabilities.

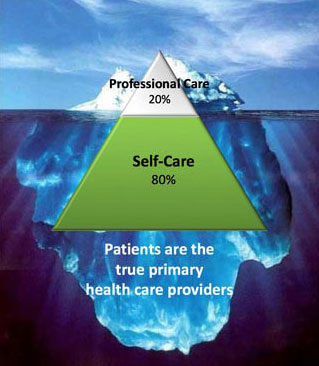

Rather than providing solutions for problems, the sessions are highly interactive involving practice and feedback in decision-making and problem-solving skills. Similarly, the focus is on increasing patients’ self-efficacy and confidence in their ability to manage their condition. Patients also develop skills to enhance physician/patient partnership by monitoring and accurately reporting changes in their condition and actively sharing concerns, questions, and treatment preferences. While health professionals are primarily responsible for medical management of the disease, the patient is primarily responsible for the day-to-day management of the illness. In the domain of living with a chronic disease the patient becomes the expert.

The desired outcomes of the intervention focus on quality of life, functional status, emotional well-being, and healthcare utilization rather than learning about their specific diseases. The goal is to get people to focus on healthy living while minimizing the time, attention, and disability associated with their diseases. Several research studies have shown those participating in the course experienced significant improvements in confidence (self-efficacy), health behaviors (such as exercise), better symptom management, and less health-related distress, fatigue, disability, and social/role limitations. They also had fewer days in the hospital and visits to emergency departments resulting in reduced healthcare costs per person in the range of $400 to $1000 per year. This equates to a potential net national savings of $3.3 billion if only 5% of adults with one or more chronic conditions are reached with this type of self-management education and support.

Family Members as Caretakers

Millions of older adults and people with disabilities could not maintain their independence without the help of unpaid caregivers. This care would cost nearly $470 billion a year if purchased.

Today there is a growing awareness of the important and at times all-consuming care provided by the family members of an ill or aging parent or other family member. Millions of older adults and people with disabilities could not maintain their independence without the help of unpaid caregivers. This care would cost nearly $470 billion a year if purchased. In the U.S. the high costs of long-term care and lack of qualified caretakers to hire make negotiating the care for a loved one with dementia or a disabling illness a nightmare and a full-time job for the caretaker who cannot afford or does not have access to help. With the aging of baby boomers, these issues are not hypothetical and the majority of those 65 years and above have neither planned for nor thought about the consequences should they require care. In the past, extended families were commonly available to assist with the aging family members. However, with today’s more fragmented family and both adults working, there is little free time for the additional care tasks that might be required. Many countries have taken a more creative track to solving the needs of their aging constituency. Belgium and Germany have created systems for co-housing or elder care from their immigrant or asylum seekers populations. Co-housing and elder communities that provide services to an aging population have also been applied in countries like Sweden and Norway.

Supporting the caretakers is important for their well-being. In 2018 the CDC recognized this important role and declared this topic a public health issue.

We see that in both chronic disease and caring for someone with chronic disease, people are not just consumers of health care, they are the true providers of primary care in the healthcare system. Increasing the confidence and skills of these primary-care providers can make health and economic sense particularly given the reality of living longer with chronic diseases.