Indus-Sarasvati Civilization:

Who Were They and What Did They Believe?

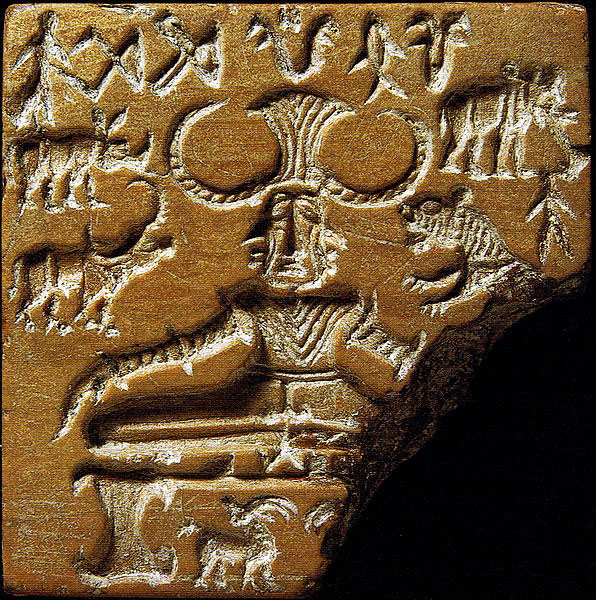

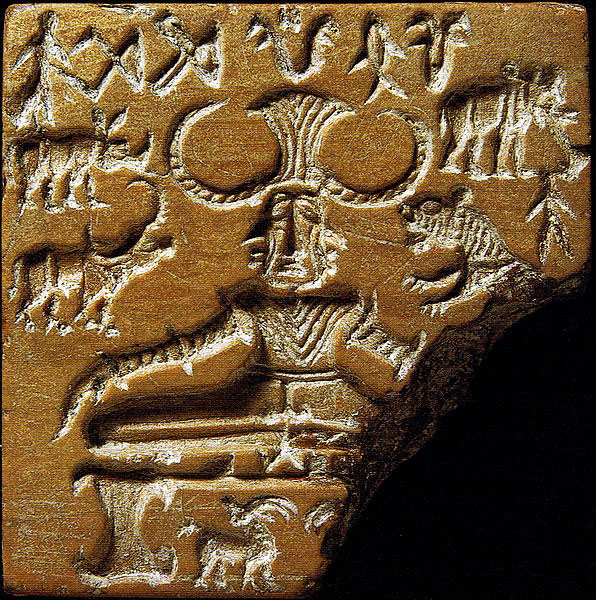

We know almost nothing of the Indus-Sarasvati people or their religion. Speculations on the meaning of figurines, depictions on seals, etc., are just that. But, since no one has as yet deciphered their writing, we are left in the dark.

Although no ancient DNA samples have been found within the Indus-Sarasvati Civilization sites, outlier samples from skeletons close by indicate a mixture of Iranian agriculturalists and South-Asian hunter-gatherers (ancient ancestral South Indians.) They show a relationship to almost all Indians today but with no trace of Yamnaya DNA. This leads scholars to conclude that the Indus-Sarasvati civilization is the likely the source of the many Dravidian languages spoken in the south of the Indian subcontinent.

There are no archaeological or genetic indications that the dissolution of this splendid civilization was brought about abruptly or by an invasion.

The failure to decipher the script has left many important questions unanswered, including the very identity of the Indus people. Their civilization appears to have developed and thrived without warfare or violence, but we don’t know what the power structure looked like in these towns or across the greater civilization. We don’t know if there was a central government or ruler, but indications are that there was not since there are no palaces; and very few structures can be identified that may have had a religious function. Not a single seal depicts a battle, a captive or a victor, and there is no evidence anywhere of armies or warfare, slaughter, or man-made destruction in any settlement, at any phase of this civilization. Fortifications and the few weapons that have been found can be accounted for by the need for protection against floods as well as perhaps local marauders, and for hunting. Notwithstanding, their civilization seems to have been highly organized, building cities of uniform planning, each producing almost identical artifacts like pottery, seals, weights and bricks, and trading over vast distances from Central Asia to Mesopotamia for centuries.

There are no archaeological or genetic indications that the dissolution of this splendid civilization was brought about abruptly or by an invasion. As the drying period progressed, the Indus too, a glacier fed river, appears to have flooded less reliably. The cumulative impact was not so much a collapse of the Indus-Sarasvati Civilization as a gradual return to rural farming centered on smaller settlements and a broad-based migration towards the eastern river basins in northern India with its more humid climate. The Indus-Sarasvati floodplains were no longer a major civilization. What is known as the post-Harappan, post-urban or “localization” era, dated about 1900–1300 BCE, followed. It was a time of instability and scarcity that eventually transitioned into the first historical states in the Ganga region. In the Yamuna Ganges valleys a new Vedic tradition emerged, featuring its own cities, script and religious practices.

During the Late Bronze Age, bull-leaping and bull-taming began to appear in other parts of the world such as Syria/Turkey, Egypt and Crete. This raises the question: did migrating Indus tribes take this custom to these distant lands?

The debate about the nature and the origin of Vedic culture has been contentious and divisive, often informed by bias and politics. Historically there are two opposing theories: the Euro-centric “Aryan invasion theory” and the equally one-sided Indo-centric “Indigenous origin theory.”

“The language of the Vedas is so close to the Avestan and its cultural assumptions so close to the Gathas that it is almost certainly an Aryan scripture.”

Most scholars today agree that while some Sanskrit-speaking Aryans were creating mayhem on the steppes, others had begun to migrate to the south, travelling in small bands through Afghanistan and finally settling in the Sapta-Sindhu, “The Land of the Seven Rivers.” Given the limited evidence, the scholar Karen Armstrong in her book The Great Transformation puts it best:

“Our only sources of information are the ritual texts, composed in Sanskrit, known as the Vedas (Knowledge). The language of the Vedas is so close to the Avestan and its cultural assumptions so close to the Gathas that it is almost certainly an Aryan scripture. Today most historians accept that during the second millennium, Aryan tribes from the steppes did indeed colonize the Indus Valley. But it was neither a mass movement nor a military invasion. There is no evidence of fighting, resistance, or widespread destruction. Instead there was probably a continuous infiltration of the region by different Aryan groups over a very long time.”

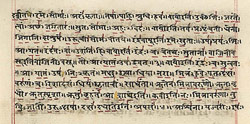

Roughly between 1700-1100 BCE, according to philological and linguistic evidence, those learned enough to do so, began to compile the earliest hymns of the Rig Veda (“Knowledge in Verse”).

As we said earlier, Iran, Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent had engaged in seasonal and trade migration for hundreds of years, so the people of the Indus-Sarasvati Civilization already had long-standing connections with regions to the west. This infiltration of Aryans may well have heightened in intensity during the severe drought beginning around 2000 BCE, but by this time aspects of both cultures may well have become assimilated. The subsequent dissolution of the great Indian Indus-Sarasvati Civilization quite likely left a regional power vacuum that the people from the west took over.

At times of danger and instability not only is there an urgent need to communicate with the Divine, but people tend to reflect on the possible end of their traditional identity and the possibility of the termination of their most cherished, sacred, beliefs and religious practices. For example, it was while in exile in Babylon that Jewish scholars began to collect and redact the memories, stories and events that would create what we know today as the Bible. So it is understandable that, roughly between 1700–1100 BCE, according to philological and linguistic evidence, those learned enough to do so began to compile the earliest hymns of the Rig Veda (“Knowledge in Verse”). This is considered the most important part of the Vedic scriptures: 1,028 hymns, divided into ten “books.”

The Rig Veda naturally reflects its people’s perennial beliefs, ancient past and their more recent histories and experiences. In the throes of establishing themselves in the Punjab, the Aryans had turned to the god Indra and away from the cult of Varuna. In the Rig Veda, Indra became the chief asura (Sanskrit for the Avestan ahura) the supreme god. Indra in the heavens reflected the time of scarcity and struggle on the earth that developed from two hundred years of drought. Indra, the god of war, was a heroic god with the power to liberate the waters from the demon and enemy of the gods: the “serpent or dragon” (quite possibly glaciers or clouds) that trapped them.

No one has any idea how old the Vedas are: scholars have speculated their origins from as early as 5000–6000 BCE.

The Hymn XII. Indra and other Hymns refer to the land of the seven rivers, and they also include praise of the Sarasvati River—“the best of the rivers” and “which surpasses in majesty and might all other rivers”—the river is mythologized and personified as a goddess, “she who has flow.”

Most scholars conclude that parts of the Vedas are much, much older, revealed to rishis, the seers of ancient times, they were absolutely authoritative and divine, having been passed down orally—with exactitude, especially because the precision of each sound was so important for these early peoples—from generation to generation through seven priestly families. As the indispensable and most valuable part of a people’s ancient oral culture, these verses would have always travelled with the Aryan or Indian peoples, and keep in mind that no one has any idea how old the Vedas are: scholars have speculated their origins from as early as 5000–6000 BCE.

“There was a vast difference in time between the earliest hymns and the latest in the Rig Veda. Hymns handed down orally during those centuries could hardly have escaped being gradually modified in their diction as the language gradually changed, and when they were at last collected into the canon, their diction would be rather that of the age when the collection was formed than that of the times when they were composed. Hence it is not surprising, if the hymns betray no marked differences of language commensurate with the long Vedic period. They were sacred, but their text would not have attained to fixity and verbal veneration until the canon was completed and closed. Yet even then phonetic changes went on, and the samhita text did not take its final shape till after the completion of the Brahmanas, or about 600 BC,” writes Frederick Eden Pargiter in Ancient Indian Historical Tradition.

One of the most beautiful passages of the Rig Veda is in the tenth book, translated here by the Sanskrit scholar Friedrich Max Müller (1823–1900). Professor Müller describes this remarkable poem thus: “We have in this hymn a most sublime conception of the Supreme Being, and while there are many Vedic hymns whose tone is pantheistic and seems to imply that the wild forces of nature are Gods who rule the world, this hymn to the Unknown God is as purely monotheistic as a psalm of David, and shows a spirit of religious awe as profound as any we find in the Hebrew Scriptures.”

“…this hymn to the Unknown God is as purely monotheistic as a psalm of David, and shows a spirit of religious awe as profound as any we find in the Hebrew Scriptures.”

We include it here not only for its beauty, but to emphasize that, in common with most ancient religions, the idea of a Supreme Transcendent spirit or god under whatever name has been with us for eons. Karen Armstrong says in The Case for God “We know, for example, that the ancient Aryan tribes, who had lived on the Caucasian steppes since about 4500 BCE, revered an invisible, impersonal force within themselves and all other natural phenomena. Everything was a manifestation of this all-pervading ‘Spirit’ (Sanskrit: manya).”

Mandala X, Hymn 121

In the beginning there arose the Golden Child.

As soon as he was born he alone was the lord of all that is.

He established the earth and this heaven.

He established the earth and this heaven:—

Who is the God to whom we shall offer sacrifice?

He who gives breath, he who gives strength,

whose command all the bright gods revere,

whose shadow is immortality,

whose shadow is death:—

Who is the God to whom we shall offer sacrifice?

He who through his might

became the sole king

of the breathing and twinkling world,

who governs all this, man and beast:—

Who is the God to whom we shall offer sacrifice?

He through whose might

these snowy mountains are,

and the sea, they say, with the distant river;

he of whom these regions are indeed the two arms:—

Who is the God to whom we shall offer sacrifice?

He through whom the awful heaven

and the earth were made fast,

he through whom the ether was established,

and the firmament;

he who measured the air in the sky:—

Who is the God to whom we shall offer sacrifice?

He to whom heaven and earth,

standing firm by his will,

look up, trembling in their mind;

he over whom the risen sun shines forth:—

Who is the God to whom we shall offer sacrifice?

When the great waters went everywhere,

holding the germ,

and generating light,

then there arose from them the breath of the gods:—

Who is the God to whom we shall offer sacrifice?

He who by his might

looked even over the waters

which held power and generated the sacrifice,

he who alone is God above all gods:—

Who is the God to whom we shall offer sacrifice?

May he not hurt us,

he who is the begetter of the earth,

or he, the righteous, who begat the heaven;

he who also begat the bright and mighty waters:—

Who is the God to whom we shall offer sacrifice?

Pragâpati,

no other than thou embraces all these created things.

May that be ours which we desire

when sacrificing to thee:

may we be lords of wealth!

External Stories and Videos

The ‘Earliest writing’ found

Dr. David Whitehouse, BBC News

The first known examples of writing may have been unearthed at an archaeological dig in Pakistan.

The Rig Veda

Ralph T.H. Griffith, Translator

This is the online version of Ralph T.H. Griffith English 1896 translation of the Rig Veda. Each page is cross-linked with the Sanskrit text.