Featured Book

The Sixth Extinction

An Unnatural History

Our planet has experienced five mass extinction events in the past half billion years. The most recent occurred some 66 million years ago when an asteroid collided with earth, wiping out the dinosaurs and dramatically changing the biodiversity of life on our planet. Marine ecosystems essentially collapsed, and about 75% of all plant and animal species disappeared. We are now facing a sixth mass extinction — the current spate of plant and animal loss threatens to eliminate 20% to 50% of all living species on earth within this century. Humans are the agents of this extinction, and we can make it stop.

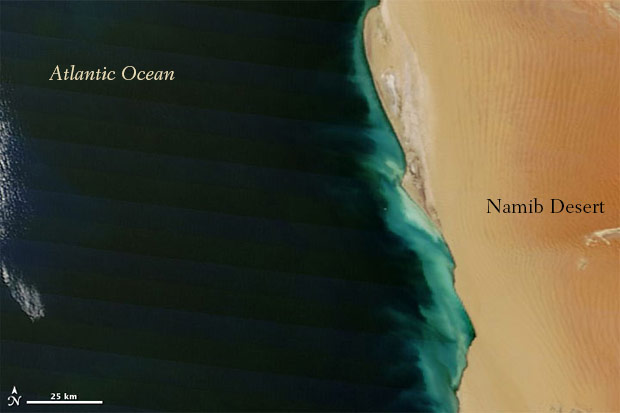

At times long stretches of the sea off the west coast of Africa turn a milky white, then an iridescent shade of jade green. Any marine creature that can do so crawls onto land to escape the water which has become laced with hydrosulfuric acid. Hydrogen sulfide gas – heavier than air, foul, and poisonous – bubbles out of the sea. The air for miles around fills with a noxious odor. Around 225 million years ago, during the largest extinction event in Earth’s history, this was the condition of all of the world’s oceans.

This deadly chemical change happens when sulfur-producing organisms are given a chance to thrive in seawater. During the end-Permian mass extinction event, also known as “The Great Dying,” oceans absorbed vast quantities of carbon dioxide from the air, depleting the oxygen and triggering a world-wide bloom of a sulfurous type of anaerobic bacteria. The seas became spiked with acid and the air was filled with poisonous gas. The result was even more cataclysmic than the later extinction of the dinosaurs.

The Great Dying is one of five mass extinctions since the “Cambrian Explosion” of about 500 million years ago, when modern animal life first took shape. Extinctions great and small happened before the Cambrian period, but conditions on Earth then were so different that they have little to teach us about the threats to life today. By contrast, the five mass extinctions since then – when at least 75% of all species on land and in the seas disappeared – are the subject of active research.

A far-reaching extinction event is happening right now. In her Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Sixth Extinction, Elizabeth Kolbert places the present extinction in line with the previous five. She recounts her personal witness to this loss, the studies undertaken to understand its causes, and the attempts being made to save just a few species.

While saving a species in captivity prevents its annihilation, it takes an extraordinary effort to return it to the wild. California condors have been brought back from the brink, but before being released they need to be inoculated against bird flu, trained not to fly into power lines, and are then often treated for lead poisoning from swallowed gun pellets. Similar efforts will not be possible for the more than 1,200 other bird species in danger of extinction. For many species, “extinct in the wild” means extinct, period.

Darwin believed that extinction is a gradual process, but the early French paleontologist Georges Cuvier understood that extinction could be sudden and catastrophic. Cuvier’s insight into the nature of the enormous and puzzling fossils then being found led him to propose that the world was once dominated by giant reptiles, and that these creatures were destroyed by a flood of biblical proportions. There was a catastrophe: 66 million years ago, the dinosaurs died within a few years of an asteroid the size of Mt. Everest colliding with the Earth near the Yucatan peninsula.

The asteroid itself didn’t wipe out the dinosaurs living on the other side of the world to the Yucatan. It was the deadly change in the climate following the impact that killed them all, along with almost anything else that lived. Climate change appears to have been involved with every other mass extinction, not instantaneously as with the asteroid collision, but in each case happening many times faster than any species’ ability to adapt.

Mass extinctions do create opportunities for new species to develop, but the recovery of biodiversity takes millions of years. And the species that vanish are not out-competed by the survivors. As a gruesome analogy, think of a terrorist bomb planted at the finish line of a marathon. Depending on the timing of the explosion, the runners bringing up the rear might be unharmed, and the best runners wiped out. This is not “survival of the fittest” – the new species are no better adapted to their new environment than the extinct species were to their extinct environment.

The present extinction has these same random and rapid properties, but it’s unique in that it’s caused entirely by the actions of a single species – humans. The impact of Homo sapiens on the natural world has been rapid and profound. Of the planet’s 50 million square miles of ice-free land, ½ has been converted to agriculture, industry, and housing. We have altered the composition of the atmosphere, and consequently altered Earth’s climate in ways that are yet to be determined. This time, we are the asteroid.

The Most Deadly Predator

The hallmark of the Sixth Extinction is the vanishing of flourishing species: the passenger pigeon, the American bison, and some species of whale, to name but a few. Kolbert describes the extinction of the Great Auk, which was once so numerous that they were burned like firewood. At one time this bird was hunted for its feathers used to adorn clothing, and many were not killed outright, but plucked and left to die of exposure! Some species today are killed for similarly senseless reasons: the rhinoceros has been thriving for 15 million years, but will certainly be poached to extinction in the wild because its horn is erroneously believed to be an aphrodisiac.

Archaic humans grew in numbers and expanded their territory in the same manner as Earth’s other large species. Neanderthals lived in Europe for more than 100,000 years and had no more impact on the landscape than any big mammal. But when Homo sapiens “arrives,” other large animals tend to disappear. Our newly evolved cognitive abilities tipped the scales of competition fatally in our favor, both for prey species and quite possibly for other human species like Neanderthals who were around at the time.

Modern humans and megafauna have been in balance only where they evolved together as in Africa, where large animals were not endangered until the arrival of Europeans. Megafauna, such as the wooly mammoth and saber tooth tiger, disappeared in every part of the world soon after the first arrival of Homo sapiens. There is some evidence of wholesale slaughter, but wanton overkills were not necessarily what finished the mammoths. Studies have found that a small band of hunters taking just one adult megabeast per year will clean a continent of that species in a couple of thousand years. Their low birth rates were a liability once human hunters were around.

Our instincts to hunt appear as unbounded as our ability to invent better weapons, and even the few remaining members of a species are targets for the hunt. The last wild passenger pigeon, perhaps the most numerous bird species in the history of Earth, was shot just over a century ago. But even beyond that, humans present a threat to wildlife that’s greater than unrestrained predation – the destruction of habitat.

You Don’t Know What You’ve Got ‘Til it’s Gone

In 1979 the Brazilian government began setting aside tracts of land in rainforests that were slated to be cleared for agriculture. This created a checkerboard pattern of nature preserves that has provided naturalists with a wealth of information, including how species respond to shrinking habitats. The pattern of habitat loss is important to this understanding – roads, power lines and the like create an enclosure effect even in preserves. Some species – plant as well as animal – move easily across gaps in the landscape, while others remain bounded in their immediate habitat.

All Earth’s species descend from those that survived numerous ice ages and the warming periods that followed by migrating to new areas similar to the climate and ecology in which they evolved. Today some plants and animals are already relocating in response to climate change, but for many species the globe is warming too fast – faster than any previously known warming – and the habitat may already be too fragmented to accommodate similar migrations. As Kolbert puts it, “… the world is changing in ways that compel species to move, [but] … prevents them from doing so.”

The Body Snatchers

While loss of habitat is the greatest single cause of the reduction in biodiversity, loss due to competition by invasive species is not far behind. Invaders arrive without their predators, giving them an enormous advantage over native species in the struggle for resources. Every year more non-native mammals, birds, insects and so forth arrive in the U.S. than there are native species. Most invasive species do no harm to the natives, but those that do can be devastating. In the last five years, white nose syndrome, a fungal infection from Europe has killed 95% of the bats in the eastern U.S. Since bats devour massive numbers of insect pests, the infestation is expected to cause significant harm to agriculture.

Ten years ago the golden frog was the signature species of the Panamanian rainforest. Today it probably exists only in captivity, a victim of another fungus known as Bd that attacks the frog’s skin, basically suffocating it. There are 7,000 species of amphibians world-wide, mostly frogs, and it’s estimated that 30% of all amphibians are infected with the fungus. Already stressed by habitat loss and pollution, and now with the added stress from Bd, amphibians have become the most endangered class of animal, dying at perhaps 45,000 times their natural rate.

The fungus is spread by people transporting types of frogs that had evolved an immunity: the African Clawed Frog, for example, is a host for Bd but is itself immune. Still, how the fungus is now in so many remote and formerly pristine locations, like the Panama rainforest, is a mystery. Humans have connected the biology of even the remotest places to everyplace else. A count taken during a single summer in Antarctica revealed that tourists and researchers inadvertently brought with them more than 70,000 seeds!

In Hot Water

We have increased the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere to levels higher than at any time since humans first evolved, greater than any time in the last 15 million years. This will likely increase average global temperatures by 2°C to 4°C, enough to melt the polar ice caps and inundate coastal areas in the ensuing rise in sea level. Climate change will intensify all of the existing threats to wildlife and comes with its own new and unique dangers.

Coral reefs are under heavy and increasing pressure from a variety of sources. Reefs are the marine equivalent of tropical rainforests, supporting 25% of marine species. Today “coral bleaching,” spurred by higher water temperature has contributed to a 50% decline in the Great Barrier Reef in the last 30 years, and 80% for reefs in the Caribbean. “Ocean acidification” is another peril for reefs. Oceans absorb 30% of the CO2 produced by human activities. This absorption is slowing global warming but it is making seawater more acidic.

Remember, ocean acidification was likely the coup-de-grâce of the largest mass extinction in Earth’s history when 90% of all species perished. And oceans today are acidifying much faster than they did during “The Great Dying.”

To observe the effects of ocean acidification first hand, Kolbert dives near an island in the Mediterranean where a natural vent emits carbon dioxide into the surrounding sea. The water gradually becomes more and more acidic (one could say “less basic”) the closer she gets to the vent. When the pH drops to 7.8, a tipping point is reached at which even the shells of the mollusks and crustaceans that do survive are weak and almost transparent. Kolbert states that if the current rate of CO2 absorption continues, all of the world’s reefs will be dead or dying in less than 50 years.

The Magnitude of the Sixth Extinction

At what point does this situation change from tragedy to danger? It might not take many species lost, compared to the extinctions of the past.

The most widely accepted counts of endangered species are produced by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (ICUN). The chart below, based on the 2017 IUCN Red List of Endangered Species, shows the percentage of some groups of species that are listed as either critically endangered, endangered, or vulnerable.

The threat to mammals captures most of our attention. Of about 5,600 total species of mammals (which includes ourselves), some 1,178—or more than a quarter—are at risk.

While the percentage of mammal species at risk has not increased greatly in the last 10 years (from about 22% to 26%), those that are threatened are in much greater peril. Recent estimates list 202 mammal species as “critically endangered” – meaning possibly already extinct in the wild – and another 476 as “endangered” – expected to soon be extinct. These numbers represent a 54% increase over the past 10 years in the percentage of mammal species in these two most endangered categories. Included are such familiar animals as two humped-camels, mountain gorillas, giant pandas, and chimpanzees, the latter likely to be gone from the wild in 10 years. Once an animal is listed as vulnerable, its slide toward extinction does not take long.

The numbers and types of individuals disappearing is also important. For example, recent studies show that 90% of the largest fish in the oceans are gone. Even though large numbers of a species might be left, the remaining individuals are, on average, much smaller and younger.

A study from Germany finds that even in protected areas, populations of flying insects have declined to less than ½ their numbers. Many of these creatures play a critical role in our own food chain. As Dave Goulson, a member of the team behind the study puts it, “If we lose the insects then everything is going to collapse.”

Who Will Inherit the Earth?

The biologist Chris Thomas, lead author of a widely cited 2004 study detailing the threat of climate change to biodiversity, attempts to put forth a different, more optimistic view than Kolbert. In his book, The Inheritors of the Earth, he argues that although humans are the cause of this present-day extinction, humans are part of nature, all that humans do is part of nature, and so this extinction too is a natural event.

He writes that “… the basic expectation of a warmer and slightly wetter world is that the diversity of many – perhaps most – regions in the world will increase” just as it did following previous extinctions. He says that this expansion is already underway, emphasizing that many species, such as crops and livestock, have benefitted from human activity. He recounts how the introduction of an invasive species to an ecosystem can even increase diversity.

On the heels of this logic, Thomas argues– alarmingly – that there is no value, and there will be no success, in preserving the natural world as it is, and that much of the work to protect existing species is a waste of time and effort. He claims that the vanishing species are simply losing out to those better suited to adapt to the human-dominated environment.

This is clearly wrong, and dangerous in its implications.

We’ve already seen from previous extinctions that the loss of species has little to do with suitability to the changing environment. But even more problematic, this view discounts what is being lost, the specifics of what is changing, and what these changes mean for some human populations. Along with crows, cockroaches, and coyotes, humans would likely survive, but human civilization is more fragile than the human species.

Some 90% of the world’s wheat varieties, for example, have no resistance to a new type of rust that is now spreading from African tropics into Asia. Wheat supplies 30% of humanity’s calories, a kind of dependence completely unknown to our ancestors.

A “warmer and slightly wetter” world does not describe the extension of the Sahara southward into what used to be fertile African farmland, or the desertification of the American West. It says nothing about the consequences of the melting of Himalayan glaciers, or the disappearance by the end of this century of coral reefs, home to 25% of ocean species.

Mass extinctions do create opportunities for new species to develop, but the recovery of biodiversity takes millions of years. Meanwhile, when there are fewer fish to catch, many people around the world go hungry. It is of no comfort that new fish will appear thousands of years from now.

The Sixth Extinction, which may expand to include us, is not a natural event. There is no massive outburst of gases from gigantic volcanoes poisoning the air, nor has Earth’s orbit shifted so that its surface is covered in ice, both of which have happened. Humans are the agents of this event, and we can make it stop. Many people are working to do so, and more people need to be convinced to cooperate.

Contrary to Thomas’ assertion, real hope is found in the successes of those who understand honestly what is being lost, and who are working hard, in some cases even risking their lives, to save what we can.

In Inheritors of the Earth, Thomas relies on data from the IUCN Red List. We can check his views against the Living Planet Index, population counts of vertebrates that are cited by the IUCN. This census has been taken since 1970 for thousands of species – mammals, birds, fish, and so on. In the chart below, the black line shows the total counts and the green line shows the counts in protected areas. We can see that conservation efforts, while far from perfect, are clearly effective.

“Hope is the Thing with Feathers” – Emily Dickinson

Sadly, a young man shot the first breeding whooping crane released back into the wild. On the other hand, volunteers in ultra-light aircraft help whooping cranes bred in captivity find their way to their wild breeding sites. In the end, we have to ask ourselves, what kind of species are we? What kind do we want to be? We have the ability to at least mitigate the effects of what we have done. We have to change the way we deal with nature, or nature will surely change the way it deals with us.

In the series: A Sustainable Planet

Further Reading

External Stories and Videos

A Few Species of Frogs That Vanished May Be on the Rebound

Carl Zimmer, New York Times

Scientists have feared mass extinction of amphibians due to a global infestation of an aggressive skin fungus. Some species seem to be slowly reappearing and researchers are working to understand what’s behind the comeback.

Destruction of Nature as Dangerous as Climate Change, Scientists Warn

Jonathan Watts, The Guardian

Unsustainable exploitation of the natural world threatens food and water security of billions of people, major UN-backed biodiversity study reveals.

Watch: The Sixth Extinction

It’s Okay to Be Smart

This time, we’re the asteroid. A history of mass extinctions.

Watch: The Sixth Extinction: Elizabeth Kolbert

Elizabeth Kolbert, Heinz Award-winning staff writer for the New Yorker and author of Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change (2006), discusses her book The Sixth Extinction at OSU.

Saved: The Endangered Species Back from the Brink of Extinction

Robin McKie, Observer

Human activity has put wildlife around the world at risk, but many creatures are now thriving thanks to conservationists.