Featured Book

The Axemaker’s Gift

Technology’s Capture and Control of Our Minds and Culture

James Burke and Robert Ornstein

Paperback edition 1997

Each time the axemakers offered a new way to “cut and control” the world to make us rich or safe or invincible or knowledgeable, we accepted the gift and used it. And when we changed the world, we changed our minds, for each gift redefined the way we thought, the values by which we lived, and the truths for which we died.

« Tools and the Development of Contemporary Society « Perspectives on the Evolution and History of Tools

The Axemaker’s Gift is a book about the people who gave us the world in exchange for our minds.

They are the axemakers, whose discoveries and innovations, over thousands of years, have gifted power in innumerable ways. To emperors they gave the power of death, to surgeons the power of life. Each time the axemakers offered a new way to make us rich or safe or invincible or knowledgeable, we accepted the gift and used it to change the world. And when we changed the world, we changed our minds, for each gift redefined the way we thought, the values by which we lived, and the truths for which we died.

And because each axemaker’s gift was so attractive, not evil or ugly, we always came back for more, unmindful of the cost. Each time there was no choice but to adapt to the effects of the change that followed. This has been true for every generation of our ancestors since the process began, well over a million years ago. When we used the first tool to cut more food from nature than nature was ready to offer, we changed our future. As a result, there were soon many more of us. And as our numbers grew, so did the power of those who could wield the axe most effectively. They became leaders. Most of the rest of the group followed the axe.

In a fundamental schism that would last until modern times, the gift of an axe favored those in a community who were good at handling the new tool and the change it could bring.

For tens of thousands of years, it has been our practice to use the axemaker’s gifts to take what we wanted from the world without recompense. All that mattered was a rising standard of living. Only rarely, if ever, did we look back to examine the effect of our passage on the world, because progress always led us forward toward the horizon we never expected to reach. Unless we can appreciate that axemaker gifts have always unleashed the kind of power that changes minds, we will not recognize that our survival now depends on harnessing the same power to save ourselves.

The axemakers are those who had the talent to take the pieces of the world and reshape them to make the tools to chop up the world. The precise sequential process that shaped axes would eventually generate language and logic and rules which would formalize and discipline thinking itself. Thanks to their talents and gifts, things have never been the same again.

With ecological and other disasters staring at us, we must appreciate that the gifts have always unleashed the kind of power that changes minds. What we need is a new mind, and we have the means to make a new one. All we need to do is find out how it has always been done and do it to ourselves. That is the purpose of this book.

The story begins with the axemakers of ancient Africa.

Getting an Edge – the Axemakers of Ancient Africa

Homo habilis was the first creature to create real stone tools. Cobbles made by a fracturing process have been found in Ethiopia. These tools are what enabled us to break the link with nature, and to begin a process which has imperiled all life on the planet. The tools enabled Homo Habilus to build shelters, and to hunt in groups. These developments led to a more stable home base, and a more permanent society. These activities also laid down the mental matrix for thought, language, and culture.

By 2 million years ago Homo erectus had appeared, with even more sophisticated tools. Tools from this time period have been found in Kenya and Tanzania. Slightly later, the first double-edged axes appeared, a major refinement in the usefulness of the stone implements. Homo Erectus had facilities for the mass production of axes by 700,000 years ago. These axes have been found throughout Africa, the Middle East, Europe, India, and parts of Southeast Asia. The techniques for making these more advanced tools required increased communication – this stimulated advances in mouth noises.

Fire had been discovered by 600,000 years ago, and by then our brain size had doubled. The discovery of fire affected our physical evolution – softer food allowed smaller teeth, making room for even larger brains and enabling speech. The tools and our bodies were interacting, with advances in technology being reflected in our physical being.

The tools enabled easier food acquisition, and larger, healthier populations. But whatever the tools, perhaps the most powerful and long-lasting change they brought about was that affecting the behavior of the communities using them. The wizardry of making these artifacts conferred power on the axemakers, and in turn, on those who could use the tools to do new things. So in a fundamental schism that would last until modern times, the gift of an axe favored those in a community who were good at handling the new tool and the change it could bring. Through the coming millennia, power would very often flow to this analytic type, who could turn the gifts to cut-and-control to his own advantage. It was as if the axe had generated a kind of artificial environment, in which those who were best at using technology to shape the world (and those around them) became leaders.

Environmental changes required further adaptations for our ancestors. 120,000 years ago, the Sahara dried up, and the climate of Africa became harsher. This stimulated movement from the ancient cradle of the Rift Valley, towards the north and east. By 95,000 years ago, very sophisticated tool-making kits existed in the Nile valley. By 90,000, we had reached the Middle East. Traveling at an estimated 200 miles per year, by 50,000 years ago we had traveled across Europe, and to New Guinea and Australia. Siberia was reached 25,000 years ago, and the far reaches of the America’s by 15,000 years ago. The ‘modern’ tool kits allowed the small bands of that day – probably averaging 25 people per group, covering an area of 15 square miles – to rapidly adapt to all environments.

Europe of 20,000 years ago was in the midst of an Ice Age. Conditions required even more communication between groups, and new levels of cooperation between groups in order to survive. Round female-like totems, dubbed “Venus” figurines appeared about this time. These seem to have been identity tokens used by the various groups to show kinship to each other. The figurines appear increasingly throughout Southern Europe, in an area stretching over a thousand miles from western France to the central Russian plain.

Around this time another kind of artifact appeared. These magic objects are referred to by modern archeologists as “batons,” and they are made of carved bone or antler horn. These appear to be an early form of record keeping, our first external memory. Marks have been carved into the baton in sets, each set placed horizontally in a line. Their existence is evidence of the highly developed stage of their maker’s intelligence.

In return for the security of protection, possessions, and food, we traded the ancient hunter-gatherer freedom of movement and the right to change our leaders, for royal dynasties that ruled by divine right and codified our behavior with the rule of law.

The earliest batons have been found in the Southern latitudes – France, Italy, and Spain – the areas from which the ice first receded. These batons show knowledge of the periodicity of nature, and could be used to predict climate by their wielders – the shamans. They could not be used by the uninitiated. Dating from 13,000 years ago, the French “La Marche” bone showed what appears to be a 7.5 month calendar, corresponding to the months of March through November (thaw to frost).

The batons indicate the ability to abstract and symbolize. They also reveal a highly developed capability to observe and record celestial phenomena. These devices enabled planning and put power into the wielders hands. They were a new kind of gift. The symbols on them were visible, but were incomprehensible to all but a few. The group became dependent on this knowledge, and the people who could wield it.

Token Considerations

12,000 years ago the world population was roughly 5 million people. At this time the axemakers presented us with two gifts. And, as would be repeated throughout history, we had no choice but to accept them. These gifts were the gifts of agriculture and writing.

Evidence of ‘dry stick’ farming in Israel has been found dating from 15,000 years ago. Grinding stones and primitive sickles have been found. These enabled more efficient food cropping. This, in turn, led to more permanent homes, and a stronger tie to particular locations.

Our behavior and these locations became linked. Burial sites at this time began to show signs that ‘ordinary’ people were being given burials, and names. Until this time, this practice appears to have been restricted to the leaders or Shamans. Stronger group identities also were evolving.

The first settlements appear to have been among the Kebakans on the plains of Levant (Syria). 11,000 years ago there were maybe four families living there. By 9000 years ago, there were nearly 200 houses at Mureybit, in modern Syria.

Axemaker gifts often trigger self-fulfilling prophecies because they create problems that only they can solve.

The production of excess food, and the increase in efficiency in producing it enabled the creation of classes of people not directly involved in food production. Tool production, basket weaving, and other arts were being practiced on a much wider scale, by specialists. 7000 years ago, pressure either from population growth or a climate change giving less rainfall, moved farmers living near rivers to move from dry farming to irrigation techniques. This represented a breakthrough in thought, such that for the first time we realized that natural processes could be reproduced artificially. Nature could be subjected to ‘cut and control’ methodology, and society could be as well. Organized survival required levels of obedience, new constraints on behavior, and new layers of social authority. Now we lived in places, and our identity was tied to the area where we lived.

The food surplus stimulated another axemaker’s gift – writing. In the beginning, it was numbers, not words, however. The surplus meant food could be stored, traded, or used as payments for goods and services. This necessitated some form of record keeping which seems to have been invented 12,000 years ago in the Zagros Mountains. These were clay tokens representing different commodities in specific quantities. Their use spread throughout the Middle East until about 5400 years ago.

The tokens were carried in clay envelopes, which often carried the official seal of the local authority. The shapes of these tokens (a shape representing a particular commodity) standardized early. These were among the first kiln-fired objects. As agriculture, animal husbandry, and artisan’s output increased, the types of tokens proliferated. About 5000 BCE, in Syria or Iraq, the number of tokens inside began to be written on the outside of the clay envelope. This led, almost inevitably, to the elimination of the tokens; the tally on the envelope, combined with new pictographs depicting the commodity of interest, began doing the job formerly done by the tokens themselves. Increases in the complications of trade stimulated the need, and search for, arithmetical operations to simplify the transactions. This appears to have been first accomplished in the Mesopotamian city of Uruk, around 5000 BCE.

Uruk appears to have been our first city. It was settled around 7000 years ago on the banks of the Euphrates. It grew after 3100 BCE to a population of about 20,000 people. This concentration of people in one place made them (and their food supply) vulnerable to external threat. The response to this vulnerability was a concentration of power in the leaders, and the development of a rigid hierarchy in the society. We decided that the rewards of city living outweighed the constraints on our behavior that were a result of the new structure.

This culture possessed the ox-drawn plow for farming; the wheel and sail for transportation; and the potter’s wheel for making storage containers. They also possessed kiln-fired bricks, metal weapons, and draft animals. From this point on, humans experienced an ever-accelerating pace of change, up to the current day. With these new gifts/tools dawned the realization that we could make large scale changes to the world around us.

The power in this society was concentrated in the King, with much of that dependent on the few scribes who could record the transactions of trade. The merchants carried out the actual trade, soldiers ensured defense (and compliance), workers made the trade goods, and farmers supported the entire chain. The production of goods was made possible by the surplus of food; the results of all of these processes went towards the support of those at the top.

Then, in a development which would happen again and again throughout history, advances in technology forced these structures to adapt. Simplifications in the pictogram systems presented those in power with a choice – face social collapse, or allow larger segments of the population access to the new technologies of reading and writing. This diffusion of the axemakers knowledge allowed the existing bureaucracies to expand. This, in turn, allowed the federation of cities into states.

More layers of bureaucracy meant more division of labor, meant more complexity. More procedures had to be standardized, meaning more of it had to be written down. This led to these procedures becoming unalterable policies. This led, in Mesopotamia, to the invention of Law.

In ancient hunter-gatherer society, the prime mechanism of social control was kin revenge. In India, China, and Egypt, this evolved into religious functions being the primary means of social control. In the Middle East, this was done by the position of the King. Concentration of this function in the person of the King also led to the idea of property, and to the first written laws. Ur-Nammu issued the first legal code in 4050 BCE in Nippur. This was related primarily to the establishment of standard weights and measures. These steps also led to a shift from communal ownership of property to private ownership.

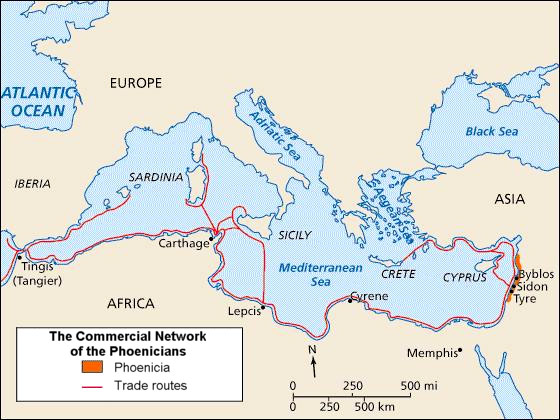

Trade, and the resultant power, was facilitated by agriculture and writing. The existence of papyrus in Egypt made their writing more versatile than that of Mesopotamia. This facilitated the expanse of an even greater trade network. Writing was language specific, and thus contributed to the solidification of those languages. The alphabet was invented, in part to facilitate Canaanite/Egyptian trade. In Greece, the spread of the alphabet triggered the development of modern thought, and further increased the gulf between the haves and have-nots.

Even by this early date, axemaker gifts had already given us the ability to perform miracles. We had used them to emerge from the jungle, first to small, regularly fed agricultural settlements and then to large, well-ordered cities. There, in return for the security of protection, possessions, and food, we traded the ancient hunter-gatherer freedom of movement and the right to change our leaders, for royal dynasties that ruled by divine right and codified our behavior with the rule of law.

Concentrated and regimented in the cities, bound by rigid conformity, we were conveniently ready for the next great axemaker change. In return for the gift of the alphabet we had accepted, we would have to accept a new measure of conformity in the way we thought about thinking.

ABC of Logic

Aristotle provided the ultimate philosophical bulwark for the ‘cut and control’ faction. He formalized deductive reasoning, and standardized thinking.

Axemaker gifts often trigger self-fulfilling prophecies because they create problems that only they can solve. In Egypt and Mesopotamia and the other riverine civilizations, the fact of living together in such large numbers (made inevitable by the reasons for which we had been led to settle down in the first place) created the need to organize and quantify the products of the agricultural techniques we then used to survive. The food surplus raised the population and boosted commerce to the point where regulation through writing was the only alternative to chaos. Regulation in turn standardized behavior through legal regimentation. And, of necessity, living within walls brought a new hierarchical attitude toward each other. We had been freed from the vagaries of nature to be deviled by regular meals.

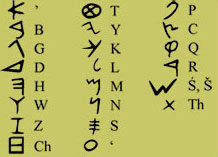

Our alphabet reached its modern form 2500 years ago. Many of the refinements in the alphabet can be attributed to the Phoenicians of around 1000 BCE. The Phoenicians were the ultimate traders in the ancient world, and the alphabet helped them in communication with people of different languages. Thus, trade benefited from, and helped to spread, the alphabet.

The Greeks of that time already had a flourishing culture, having adopted many things from other societies. They brought arithmetic from Mesopotamia, geometry from the Egyptians, and metallurgy from the Assyrians. They adopted the alphabet from the Phoenicians, and this adoption seems to have occurred in a single place, since the form adopted all over Greece contains the same transcription errors with respect to the Phoenician alphabet.

The alphabet codified nature, and allowed further advances in our ability to ‘cut and control’. The alphabet allowed written records of events – history was invented. The ease of learning the new tool caused literacy to spread. Our external memories were greatly enlarged. Thinking could be publicized. This allowed Democracy to develop, and education to improve.

After Plato’s death, Aristotle moved to Asia Minor. Here he considered the problem of how the mind (which to him was separate from and superior to the world) acquires an understanding of matter. Aristotle provided the ultimate philosophical bulwark for the ‘cut and control’ faction. He formalized deductive reasoning, and standardized thinking. His method came to be called logic. He categorized all organisms according to a single matrix: The Great Chain of Being. After Aristotle, certain things were allowed to be thought, and others were not.

The new ways of thinking were mirrored in all aspects of Greek life. Strato of Lampsacus was doing scientific experiments by 250 BCE. He became head of the Mouseion at Alexandria, where Archimedes and Aristarchus worked. Euclid, Apollonius, Herophilus, Eristratus, and Eratosthenes also worked here. The transition to this new way of thinking was reflected in the evolution in Greek drama, from early religious forms to the later Greek tragedy.

It is perhaps too easy to view the rise of Greek thought, epitomized by Aristotle, as the first magnificent attempt to free the human mind from the grip of thousands of years of ignorance and blind ritual. But this view is itself constrained by the fact that what happened twenty-five hundred years ago in Greece shaped the way we ourselves see those events. Our thinking is the product of the Aristotelian system of logic, which itself was designed to prevent the anarchy made so frighteningly possible by the alphabet and made so seductive by the Sophists.

In an echo of the way the earliest axemaker gifts were used, the enormous value to those in power of this new mental tool was that it let them cut to the core of the world in order to find the essential order in all things and then to use that order to shape social behavior appropriately. Deductive reasoning standardized thinking as never before. Logic cut at the root of free thinking before it could become anarchic, or develop in whatever alternate form, and would go on doing so over the following two thousand years. It would take that long for another revolution in language technology to offer the human mind a second chance.

Faith of Power

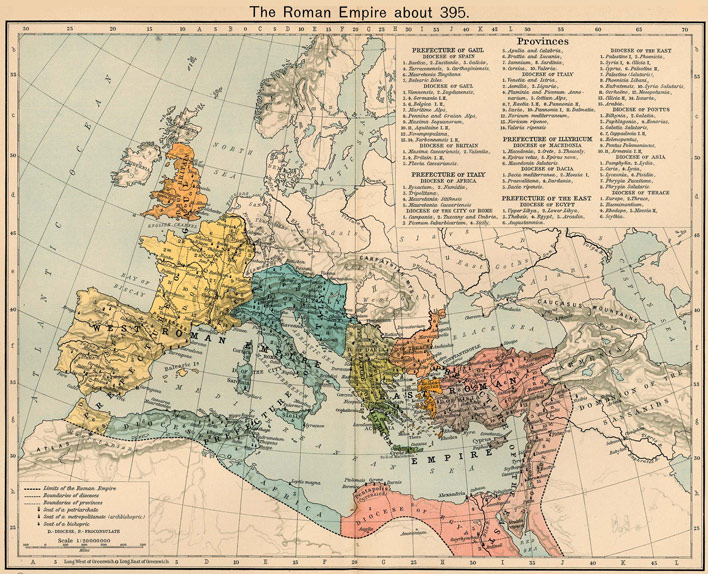

By the time Rome emerged as an imperial power, the axemakers had provided the means for a small elite to live in relative comfort and order, and for the majority to involve themselves in a myriad of different activities. In the fifth century when Rome fell, it seemed to its citizens the end of civilization was near.

Once again axemakers came to the rescue. This time their gifts, in the form of Classical knowledge preserved almost intact throughout the Dark Ages, would place in the hands of a single central authority more power over more people, who would conform to more rules of behavior more extensive and constraining than any that had gone before. If the Mesopotamians defined the social structure and the Greeks shaped thought, the new constraints that came in the early Middle Ages would narrow the individual’s options even further. These axemaker’s gifts would make it possible for leaders to control their followers’ most fundamental personal beliefs.

In 1455 there were no printed texts. By 1500 there were 20 million books in 35,000 editions.

After the fall of Rome, the Celtic monasteries in France, Italy and the British Isles became transition points from which the knowledge of the ancient world would nourish and give birth to mature medieval thought. This was a time for intellectual consolidation, rather than new knowledge, so the church tried to preserve what it could with vast compilations of axemaker knowledge. In the 8th century, St. Boniface began accumulating texts. The English monk Bede, and Isidore of Seville began compiling encyclopedias of knowledge. For centuries, these compiled texts would be the only source of knowledge about nature in Europe, and the Church would control access to it.

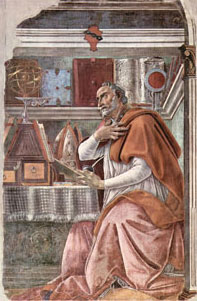

The Church modeled itself after the Roman hierarchy. St Augustine, in City of God, published in 424, set the framework for earthly Papal power, with the Pope the representative of heaven on earth. The knowledge of the monks helped the church suborn the secular monarchs, most of whom were illiterate. Over the next four centuries, the church was able to increase its control over the rulers. Early on, Pope Gelasius I (492-496) had emphasized the primacy of papal power over secular authority. Pope Gregory set up a message network between monasteries in the 7th century. In the 8th century, the tithe became mandatory. The Paris council of 829 actually went as far as to define what the roles of kings were. From Paschal II on (1099), the Popes were the ones who crowned the kings. In the 12th century, the Popes title changed to “Vicar of Christ”, further emphasizing the ‘divine right’ to rule. Confession was made mandatory – even people’s thoughts were subject to the control of the church.

In the Arab world, other developments had been taking place. The Nestorians had carried much of the Alexandrine knowledge with them eastward. Caliph Al Mansour, in 7th century Baghdad, had set up a center of learning. Much of the Greek was translated to Arabic, and the study of certain subjects, such as astronomy, medicine, and mathematics, flourished. All knowledge had to be reconciled with the tenets of Islam however, so they could not become a threat to order.

The highly centralized nature of Islamic society, which placed tight constraints on the individual’s freedom of intellectual movement, made innovative thinking possible but its application strictly controlled. The same was true of medieval Chinese society, where at this time other axemaker knowledge was being generated, which would, like Islamic advances, eventually find its way West. In China, the state controlled all activity, and the comprehensive social organization originally required for irrigation and other large-scale public works gave Chinese life a collective character.

When Toledo fell to the Christians in 1085, this knowledge started back towards the West. The diffusion of this knowledge back to the West would give the Catholic leadership unprecedented power to cut and control. The thinking of the monasterial groups, epitomized by the Cistercians, was that nature existed to be improved, and dominated. In the 12th century, the Cistercian abbot, St. Bernard of Clairvaux, France, described the extent to which, in his monastery, nature had been suborned to the service of man. The structure of the Cistercians was much like modern factories, with every facet of nature bent to man’s dominion. The invention of clocks also provided for more effective marshalling of social forces. An ordinance was issued in Ameins in 1355 ordering workers’ days according to the movements of the clock.

The re-introduction of this knowledge, particularly Aristotle, did contain its threats. In the 2nd half of the 13th century, universities were being formed. Some of the new thinkers, such as Abelard, were questioning the bases of authority. Abelard had, by 1110, exposed some of the inconsistencies in theology. The church was so threatened that the study of Aristotle was forbidden in 1210 at the Council of Paris. In 1277, all discussion of rationalism was forbidden.

Thomas Aquinas provided the tools to preserve church authority. He separated theology from philosophy by differentiated knowledge gained from logic, and knowledge gained from revelation. With this, Aquinas released the full power of the gift of rationalism into secular hands. Although they would labor for centuries in the name of the church, eventually they would facilitate the transfer of power to other centers.

Fit to Print

The next gift would radically change how knowledge was recorded and disseminated. It would also change the nature of knowledge itself, how it could be used, and how many people could have access to it. And in the way that all advances in communication make things more complicated, their gift would break up the monolithic social structure of Christendom and diffuse control outward to many peripheral centers of power. This was possible because, at a stroke, the new gift also increased the number of change makers.

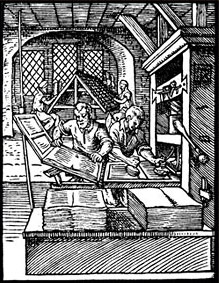

In 1439, in the German town of Mainz, Gutenberg began development of moveable typeface. The development of printing would change the map of Europe, considerably reduce the power of the Catholic Church, and later the very nature of the knowledge on which political and religious control was based.

Printing spread throughout Europe rapidly. In 1455 there were no printed texts. By 1500 there were 20 million books in 35,000 editions. More than 200 editions of the Bible had been commissioned. Presses existed in 245 cities. The century between 1500 and 1600 saw the production of 150 to 200 million texts. The most mass-produced books were the Bible, and the devotional Imitation of Christ.

In a single generation since the Scientific Revolution had culminated with Newton, science and technology were already giving us a radically new view of nature.

Rome thought the dissemination of Bibles in the languages of the people would help further entrench their power. This would prove to be a major mistake. In 1466, the 1st vernacular bible was printed in German, in Strasbourg. This was followed by an Italian bible in 1471, Dutch in 1477, and six more languages by 1500. These publications gave permanence to the languages, and areas they were printed in. Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, Wales, Ireland, Catalonia, and Finland had their own Bibles. They also strengthened unity and the power of the national rulers. Languages without printed bibles receded, and those political entities faded. Sicily, Provence, Brittany, Frisia, Rhaetia, Cornwall and Prussia faded. The languages strengthened people’s nationalistic feelings. Languages and boundaries consolidated.

The technology and economics of print production and distribution inevitably also tended to concentrate output on fewer, larger markets, so the printers themselves contributed to a rapid homogenization of the many dialects of Europe into a few major languages. The development of national languages, the loss of a Latin lingua franca, and the break-up of Christendom concentrated local control in the hands of independent national leaders.

The standardization of languages led to increased nationalism on many fronts. This could be seen most clearly in Elizabethan England. The English Book of Common Prayer was printed in 1549, and with the help of the printed word, England was a united cultural and linguistic entity by about 1600. The King James Bible was published in 1611, which further standardized language and religion. Many of the texts being printed stressed conformity and obedience to authority.

The new literacy aided kings in moving from Papal control. In 1545 Rome called the council of Trent to combat Luther. This council called for standardization of texts. Plantin was commissioned to print a ‘Royal Bible’, a huge compendium of knowledge of the Bible, its context, history, and geography. This was published in 1572. This publication, with its appendices full of information on diverse subjects, spurred a spread of knowledge through Europe. Almanacs of all types became popular. This helped to create job specialties, with special knowledge, not readily available to others. The old ways of apprenticeship were being disturbed – information could be had from books.

Throughout history, mysterious axemaker knowledge always strengthened social conformity as at the same time it increasingly distanced the change-makers and their institutional masters from the general public whose lives they controlled.

The problem for the authorities was to what extent and in what form all this novelty could be safely disseminated without causing disruption. Luther was urgently concerned with education and the indoctrination of the young. Education standardization was intense. The young were to be molded into suitable roles to support the existing power structures. Rome responded by forming the first of the Jesuit colleges in 1542. Other institutions were formed. Henry VIII formed the Royal College of Medicine in 1518, soon followed by others of their kind.

The process of streaming and grading in education helped to single out those with the potential to be admitted to positions of authority. New pedagogic experts emerged to control and administer the new indoctrination process. At Lutheran urging, curricula became official, teacher training was state-controlled, approved texts were printed, and use of the vernacular rather than Latin ensured that the new regimentation would reach down to the lowest stratum of society.

The focus of the new education was what concerned educators most: the need, in a time of rapidly growing trade and commerce, to use education as a tool for inculcating useful knowledge. Children in school were now to be given tools so that they might experience work and make their choice of vocation early. However, Komensky stressed the potential of education to control and predict human behavior: “for there will be no ground for dissenting, when all men have the same truths clearly presented to their eyes.”

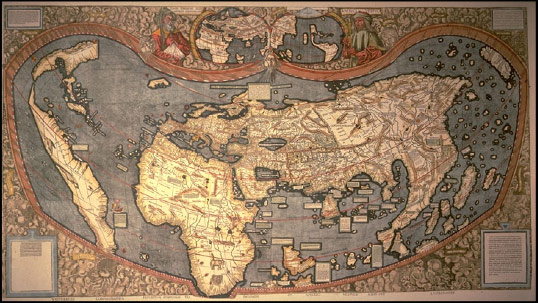

Then the whole world was turned upside down by the discovery of America.

New Worlds

In 1502 Americo Vespucci returned from his explorations of Brazil, and published an account of his journey in 1505. Waldseemuller published a map in 1507 showing continents between Europe and Asia. This caused quite a stir in Europe. The unveiling of the nature of the new world to Europe revealed that the world was not like it had been pictured, and everything was thrown into question.

From the time of the first flint tool, axemakers’ gifts had given the institutions of leadership the means to reshape the world. Each time they did, entirely new structures and systems appeared in the form of carpentered hunter-gatherer shelters, law with which to control the cities of Mesopotamia, Greek logic to enforce conformity on the investigation of natural processes, the medieval trick of “reproducing the phenomenon,” and the new, regulated, print professions. But now an entirely new kind of knowledge was to emerge as it became clear that the world was not all it seemed. The axemakers response to the problem posed by the New Worlds took the form of a gift that would bring to the community material benefits far beyond anything that had been offered before, and at the same time would remove specialist knowledge entirely from public gaze, placing it in new, artificial worlds. We call it “science.”

Galileo, working in Padua in 1603, tried something new. He worked out a problem mathematically, and then experimented to verify the math. He studied falling bodies and tried to derive a natural principle from these studies. Francis Bacon worked on developing a standardized approach to knowledge. He opened the door to new avenues of data collection. He believed that only the exhaustive gathering and classification of information would bring the kind of certainty that would maintain social stability because it would reveal, in a new way and with new kinds of evidence, the orderliness of God’s creation and the regularity of the workings of nature and society.

In 1637 Descartes published his Discourse on Method. This set rules for seeking constancy in an uncertain world. His method was reductionism, the ultimate in ‘cut and control’ methodology. According to the ‘Discourse’, anything that could not be previously categorized would not be studied. With Descartes’ reductionist axe, the selective and exclusive process of human perception, originally modified by language and the alphabet millennia earlier, was now even more constrained.

Knowledge must be controlled. Groups for the regulation of knowledge formed, like the Royal Society in England in 1662. These societies emphasized orthodoxy, and standardization of approach. It was dangerous not to conform.

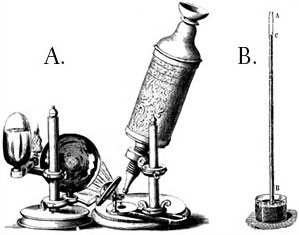

This time saw an explosion of ‘instrument’ generated knowledge, and one discovery could have ramifications for apparently unrelated endeavors. The discovery of the vacuum (which was philosophically dangerous, since it should have been impossible) stimulated developments in meteorology and chemistry. The telescope and microscope revolutionized astronomy and the medical sciences, and started a public health revolution. The world revealed by the microscope was particularly unexpected. An account of the anatomy of bees was published by Stelluti in 1625. Harvey published his theory of the circulation of the blood in 1628, and embryology was effectively formed by 1651. Biology was separating into many differentiated, specialist branches.

The twin axemaker gifts of the air pump and the microscope for the first time also linked the crafts of engineering and metallurgy with scientific theory. This in turn generated the new occupation of scientific instrument-maker and the new concept of precision. And with the proliferation of esoteric knowledge into so many new theoretical disciplines, demand surged for systems of measurement and quantification. Initially this need was most clearly seen in astronomy, where the drive to produce better lenses in turn encouraged the production of more precise ways of pointing the instruments.

The advances in technology had parallels in economics. In 1692 Dudley published his Discourse on Trade. This quantified economics for the first time and led eventually to Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, published in 1776. Here Smith formalized the concept of division of labor. John Locke applied similar thought to society; he talked of the members of society in a mechanistic way, with the force of self interest ruling each individual. America’s formation incorporated these ideas from the very beginning.

In a final, more general manifestation of its power, the scientific method also generated mechanistic attitudes in the political thinking of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe. Knowledge of the universal law of acceleration, for instance, led people to expect that the progress of society would also accelerate with the passage of time. The sole aim of government should be to make sure that nothing constrained this natural force of self-interest. Since its most common expression was ownership of possessions, then the prime responsibility of the state should be to protect individual property, leaving citizens free to concentrate on increasing their wealth.

These ideas, as expressed by Locke, would find their most powerful expression in America itself, at the birth of the United States. The industrial revolution gave America more tools to cut and control, on a planetary scale.

Root and Branch

In a single generation since the Scientific Revolution had culminated with Newton, science and technology were already giving us a radically new view of nature by suggesting that it could be “improved.” As the full force of the scientific revolution began to take effect, the cutting edge of innovation became sharper and more finely honed than ever before. The new axemaker gifts developed in the Royal Society laboratories were spreading into society, giving governments and institutions the power to change the world with unexpected speed and in unprecedented detail.

At this time, society everywhere was primarily agricultural and life on the land had altered little since the first Levantine settlements twelve thousand years ago. The early Mediterranean scratch plough had given way to the late-Roman, northern-European wheeled version, with a coulter that cut the sod and to some extent turned it over, creating furrows that made heavy soils easier to drain. For centuries most inhabitants of agriculturally based economies had lived their lives by rote, at nature’s command. This ancient cycle and the lifestyle of the large majority of the population who lived on the land were both to be totally changed by a new axemaker gift.

In 1640, a book about new Dutch farming innovations was published. The book introduced new fodder grasses – sanfoin, clover, trefoil, and alfalfa – which put nitrogen back into the soil. New methods of crop rotation allowed much more land to be put into cultivation. These advances spread rapidly, with a resulting food surplus and population growth. In 1500, roughly 50% of the available land was cultivated; by 1700 it was 75%.

The new agricultural techniques made it possible to cultivate previously infertile or uneconomic land, which could now be made profitable enough to be cut up, cleared and then fenced for use. Enclosure was a more efficient way to use the land than the old-fashioned open field because it allowed more rational consolidation of property. The new-style farmers bought up strips of land from different owners, added newly enclosed areas, and assembled large, productive unified properties. These techniques were to have profound social effects because enclosure cut off the small cottager from his acres and the sharecropper from his common grazing rights.

The profits of the landowners resulted in capital being generated, with much of this used in buying up even more land. A financial revolution was the result. This revolution would further isolate and separate people and make it possible to use money to manipulate their behavior. Capital was an exciting new kind of tool because its potential for self-increase was apparently unlimited. John Locke provided inspiration for the institutions of the day by reconciling in a new and profitable way, the concepts of universal laws, dominion over nature, and profit. As he put it, “The great and chief end, therefore, of Men’s uniting into commonwealths and putting themselves under government is the preservation of their property.”

The factory system also introduced cash wages, and these placed a premium on youth and vigor, and in doing so impaired or destroyed the authority of the old.

Capital was by now also generating major changes in social behavior as wages altered the nature of work and altered the relationship between worker and employer. Time and effort were increasingly measured not in terms of mutual responsibilities between employer and employee, but in terms of cash. As the system matured, it took the usual cut-and-control path. Manipulation of capital fragmented the production process, deskilling the workers, reducing them to units of production that could be more easily controlled. A new kind of life was created: mindless repetition of meaningless tasks set to the speed of a machine.

Smith’s mathematically expressed laws of production copied those of the earlier Scientific Revolution. According to his new “law,” to be applied by governments and institutions with increasing effectiveness, the stimulus for the division of labor was the extent of the market, and this in turn depended on the ease of exchange of goods for capital. Continued growth required an ever widening market in which transportation and financial instruments were essential tools.

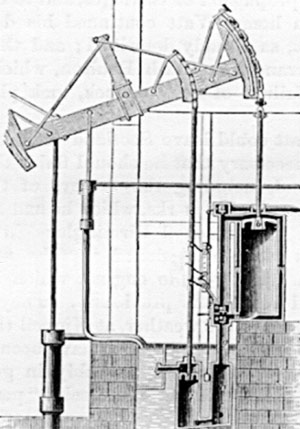

To complete this new way of operating, a new means of production was needed. One that would be less dependent on skilled workers, was more controllable, and more mechanical. Steam power was the gift which made possible the execution of the new economy. It also made unskilled labor useful, which put large downward pressure on wages.

The Industrial Revolution that steam made possible would be the greatest of all axemaker triumphs so far in history, and it would change the entire world. The revolution began in the textile industries. The inventions of the day fed off of one another. The advanced spinning machine in 1769 automated the process of thread making. By 1812, there were 5 million spindles in England, with over 100,000 unskilled workers operating the new machines. By 1850 there were 250,000 steam powered looms in operation.

The interactions of industry and science spurred massive changes. Advances in gun manufacture led to the development of interchangeable parts. The implementation of these interchangeable parts in textile machines reduced the need for skilled workers to fix the machines. These tendencies moved workers more towards the status of interchangeable parts. The interactions of these inventions stimulated surprising discoveries. The pace of change was increasing rapidly.

Class Act

In mid-eighteenth century, the axemakers had provided the means to change the shape of a tulip. Only three generations later their gifts were giving the West the means to change the shape of the planet.

Throughout history, mysterious axemaker knowledge always strengthened social conformity as at the same time it increasingly distanced the change-makers and their institutional masters from the general public whose lives they controlled. The sheer scale and number of new control systems generated by late-eighteenth-century technologists and entrepreneurs widened this gulf and imposed rigid conformity as never before. More and more, the life of the worker was being molded to fit the needs of the machine and factory. The realization that this was the case was also starting to spread.

A magazine for English factory workers was published in 1828. This talked about how the policies and gifts of the axemakers had changed them. The industrial revolution had pulled people into the cities so fast that effective facilities to control them were lacking. The horrible conditions of the new urban poor led to riots. These uprisings, and the resulting draconian suppression, finalized the concept of ‘class’.

Revolutionary works, such as that of Thomas Paine’s, were viewed with alarm by the establishment. New methods of control were needed. Propaganda, in many forms, was used heavily. The themes of discipline and submission to authority were heavily touted. The Evangelical Movement Moral Crusade was instrumental in this effort. Concurrently, more left-wing organizations were springing up. Worker cooperatives were forming, such as the London Cooperative Society in 1824. By 1831 over 500 such societies were in existence. One of the stated goals of some of these was to establish a community of property.

The establishment fought back against these trends in the schools and churches. Education took on the form of a production line. Literacy and numeracy were learned by rote – the bare minimum for factory work. The practice of writing was discouraged, to diminish the capacity for organized dissent. Sunday school was instituted in England in 1785, to clear the streets on Sundays. Members of the Evangelical movement infiltrated banking and political institutions to promote their solutions for social stability.

The left-wing offered alternatives, although they would ultimately prove to be as conformist as those offered by the establishment. In 1816, Robert Owen – in New Lanark, Scotland – modeled his factory as a community complete with shops, hospital, and a school. Part of Owen’s belief was that human progress would be impossible without first eliminating ignorance. Owen and his followers set up schools and institutions to teach the skills necessary for successful factory life. Many of their publications took forms similar to the religious propaganda of the establishment, but the hymns were not Christian, and the sermons were about social topics. While the Socialists offered to eliminate class distinctions, their emphasis was still on work, and the factory, as the center of modern life.

The new city-based industrial society cut off the people from nature, from any regard for it, and from any sense of native origin. The factory system also introduced cash wages, and these placed a premium on youth and vigor, and in doing so impaired or destroyed the authority of the old. The nature of urban communities changed as the middle classes left the city centers, not to return there until late in the twentieth century.

The concept of time also changed for workers. Time sheets, time keepers, fines for lateness were introduced. William Temple advocated poor children being sent to work at the age of four to habituate them to the rhythm of the factory. Working life was chopped up and set in orderly sequence, dominated by the need to conform to the machine.

Against this raged the emerging and equally conformist alternate systems of Socialism and Communism. In 1884, the Social Democratic Foundation stood for social ownership of the means of production and exchange and saw the retention of political power by the working class as the essential means of achieving this end. In the late 1880’s the formation of major unions of the unskilled took place under socialist leadership, strengthening the connection between political activity and industrial organization that had been lacking in the early days. At the same time, the new Socialists embarked on a program of propaganda and education of their own.

These factions set up two opposing streams which would dominate the world for the next century.

In mid-eighteenth century, the axemakers had provided the means to change the shape of a tulip. Only three generations later their gifts were giving the West the means to change the shape of the planet. The cut-and-control approach to industrial production had also removed and separated most members of European society from their previous direct relationship with the land. Their cities were now dependent for survival on cash from a factory that was dependent on raw materials from the colonies. The community had been decomposed into “units of productive labor”.

Doctor’s Order

In what would be the axemakers’ most seductive gift, in return for obedience and conformity, they offered life. 18th century medicine would change the way we viewed ourselves and life once again. Previously, no real medicine, or tools for diagnosis existed. Each person was felt to be a unique entity, and the body, mind and personality were inseparable. However, the revolutionary wars in France had left so many sick and wounded that the case for effective general therapy had become an urgent social priority. By 1807, Paris hospitals held over 37,000 patients, many of them soldiers or peasants injured in the revolutionary wars.

With these wounded peasants began the modern reverence for the doctor of medicine, who from then on began to ignore his patient. Medicine was now free to move away from therapy and healing (what the patient wanted) to diagnosis and classification of disease (what the doctor wanted). Once again, the gulf between the expert and uninitiated would widen.

Medicine rapidly found ways to reduce data on the human body to many more subcategories. Thermometers had been in use for over a century, and a standard temperature defined.

In 1816, the French doctor Theophile Laennec invented “indirect auscultation” to listen to the sounds of the chest. This gave way in 1829 to the stethoscope. These tools were able to identify emphysema, edema of the lungs, pneumonia, and tuberculosis. Chemistry made urinalysis possible with the first test for albumen in 1833. Becquerel statistically averaged the components of urine in 1841 to derive definitions of “healthy” and “diseased” states. The microscope enabled Gabriel Andral to analyze blood into its constituent parts in 1841. Other inventions followed: the spirometer, ophthalmoscope, and laryngoscope. In 1868, Wunderlich introduced the “chart” – the state of the patient had been reduced to a set of numbers at the foot of the bed.

Cholera broke out in Britain in 1831. This primarily affected the poor and destitute. The population explosion allowed by the new agricultural techniques, and the move to urbanization spurred by rapid industrialization, had made conditions ripe for epidemic. Society was pushed towards anarchy. Riots broke out in London in 1832.

The gifts of the axemakers conferred power on those few among us who were able to use them to command the community through myth and magic, or their later equivalent, science and technology.

In 1842, a report commissioned by the British government of the conditions and causes of disease was published. This report so shocked Victorian society that it led to measures that would give public institutions unprecedented powers over the private life of the individual. What was so shocking was the depiction of the appalling conditions in the cities. The sewer and water arrangements were particularly bad. Overcrowding, of humans with humans, and of humans with animals, was rampant. Most shocking were depictions of the moral problems – frequent bastardies, prevalent incest, and children forced into begging and prostitution. The report suggested that reform was necessary if a revolution was to be avoided.

A more severe outbreak of Cholera appeared in 1848. This prompted the passage of the Public Health act. This act and the Nuisances Removal act gave the government new compulsory powers to control disease. Public health considerations were to bring direct state intervention in the private life of the individual. By 1866, the authorities had found that areas with filtered water had dramatically lowered incidences of cholera. The attempts at control through quantification by statistics and draconian social control seemed to have worked. The success set the pattern of future state intervention in cases of what was now to be defined as ‘matters of public concern’.

The epidemics and the social conditions that had made their effect so devastating, had both served to strengthen the grip of the state on the community at large. Now the institutionalizing of public health, aided by developments in medical technology, would strengthen it further.

Lister developed better microscopes from 1825 to 1830. The shape of blood corpuscles was determined in 1827. 1831 saw the observation of the cell nucleus and of bacteria. The formation of cells was observed in 1851. The cell came to be regarded as the basic unit of existence, and life was no more than the sum of cellular phenomena that could now be submitted to normal physical and chemical laws, according to Virchow in 1845.

Because our lives have changed since those primeval times, it is imperative above all that we revise our out-of-date perception of the world, so that our ancient, small-scale, small-time mind can be expanded to consider more distant horizons and more frequent changes.

Thanks to bacteriological techniques, diagnosis was now able to quit the hospital ward entirely. New laboratories sprung up, first in the large hospitals such as St. George’s in London and Bellevue in New York. Public laboratories soon followed. These public health laboratories brought the combined gifts of microscopes and bacteriology to the control of public health and did away with patient involvement. There were now a growing number of specialists and institutions, concerned with the disease and its behavior, for which patients provided little more than a source of material for study. The successes of these laboratories diverted attention away from the more diffuse problems of living conditions, and established a narrow bacteriological view of disease which would remain dominant for decades.

With Western medicine we have cut apart the human body in the same way as we have, through history, separated the axemaker from the non-axemaker, subject from god-king, communicant from priest, nation from nation, and people from land. We have dissected and divided up the world and its inhabitants so that they can be manipulated as economic and political units interchangeable with one another. In doing all this, we have cut out the individual in the same way as we have chopped up the planet, axing the single parts without regard for the whole. This process has brought us close to catastrophe.

Journey’s End

The gifts of the axemakers conferred power on those few among us who were able to use them to command the community through myth and magic, or their later equivalent, science and technology. Because of this, through history, axemakers have been encouraged by those in power to innovate for them, unhindered. In particular, the gifts make it easier for leaders to extend their power to shape and direct their communities through the increasing command of information. Those who knew how to use the Montgaudier baton, the commodity tokens of the Iranian mountains, the cuneiform of Mesopotamia, the alphabet of Greece, the moveable type of Gutenberg, or the symbols of math, medicine, and science were generally free to act as if the Earth were still as limitless as it had been for the ancient axemakers of Africa.

Our survival may depend on the realization and expression of humanity’s immense diversity.

In virtually every case, though, their use of axemaker knowledge brought immediate benefit to the community, which in turn abdicated responsibility and power to them so long as immediate survival and a rising standard of living were assured in return. However, these attractive, short-term gifts have generated unattractive, long-term problems because of the way, as innovations proliferate, they interact and cause unexpected effects. Acceptance of each gift changed the way humans saw their relationship with each other and with nature.

The development of agriculture led to the innovations of Egyptian irrigation, Roman wheeled plows, the fodder crops of 17th century Holland, and 18th century fertilizers. This string of gifts has culminated in what has been called the Green Revolution. New strains of food crops were developed in the 1950s which had huge gains in yield. The catch was the dependence of these strains on chemical fertilizers, increased water irrigation, and farm machinery. The situation today is that the Third World has undertaken enormous debt to accept these crops (forced on them by the developed nations). Most of the world’s food comes from just a few species, a very precarious position. The genetic base from which future alternate food sources might come has been drastically reduced, as has the traditional knowledge-base that might have provided alternative techniques on a rainy day.

Five thousand years ago another life-saving gift that changed our attitudes was the technique of irrigation. Subsequent innovations including Egyptian “shadufs”, medieval dams and channeling, and Renaissance suction pumps have led to today’s carborundum drill bits, enormous reservoirs, and river diversion. By now, water supplies are being depleted faster than they can be replenished. Water scarcity is now common in 26 countries, including Russia, the Middle East, and the Southwestern United States.

More than 70,000 years ago specialist axemaker gifts ensured the survival of those who lived on coastlines with harpoons, hooks, and nets for fishing. Over the centuries since then we have taken food from the sea in ever-greater amounts, thanks to better ships, safer navigation, weather forecasting, radar, and the many other industrial innovations, which have made it easier to plough the oceans for their rich harvests.

Today, fish harvests are failing and the oceans are dying. Four of the world’s seventeen fishing zones are already overexploited. Contamination is also causing major salt and fresh-water problems. The southeastern Mediterranean fisheries and the oyster-beds of Chesapeake Bay have been especially devastated. The coral reefs of the world, a reservoir of genetic diversity, are being wiped out by a phenomenon known as “bleaching”.

The gift of fire 600,000 years ago provided heat in the winter, and introduced the magic of cooked food. But the scarcity of wood by the middle ages led to the search for alternate fuels. In the 19th century, electric generators and petroleum seemed to save the day. But today, the fossil fuels are being depleted, and ever more land is being scarred to procure them. The United States is particularly wasteful of these. Air and water pollution from overuse of these products is threatening the health of people all over the world. Russia is in particularly bad shape. Studies in 1993 stated that as many as 1 in 10 Russian infants suffered from birth defects. The industrialization of the world has resulted in widespread airborne pollution. This has been linked to increases in lung and heart disease in industrialized areas. Los Angeles, Tokyo, and Mexico City regularly exceed four times WHO guidelines for air quality. In 1988, over half of all newborn babies in Mexico City had enough lead in their bloodstream to cause neurological and motor impairment.

Local defects, axe marks, resulting from the use of the axemakers gifts, have always been present. But today, these local marks are coalescing into global patterns of mass destruction. The land is depleted. Erosion and soil degradation occur mainly because of the effect of wind on land after ploughing, mining, or the flooding that follows removal of forest cover. This is now affecting up to half of all land on Earth. One-fifth of all cropland has been irretrievably lost through degradation. Topsoil and arable land are being lost forty times faster than natural processes can replace it.

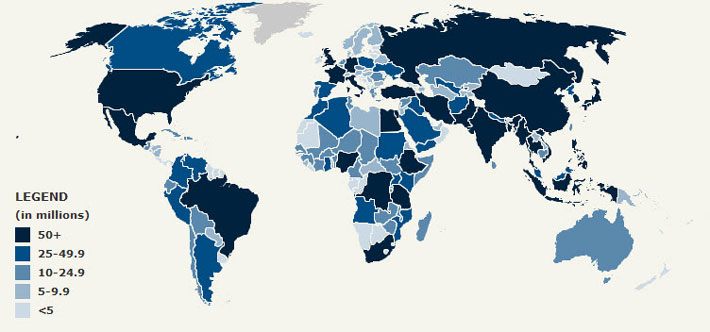

The Industrial revolution has released large amounts of CO2 and other gases which act to trap solar energy in the atmosphere. This causes the atmosphere to warm up in what is known as the “Greenhouse Effect”. Changes to the Earth’s temperature of just a few degrees could have profound effects. Past changes due to temperature variations of just 7 degrees F include the last Ice Age, the drying of the Sahara and the rise of Civilization itself in the Middle East, India, and China. A rise in temperature could have a number of consequences, such as a rise in sea level, dying out of major forests, frequent storms across the world, and a dieback of the oceanic phytoplankton. A rise in sea level could cause major death and displacement among the two-thirds of the world’s population that live on low coastal land.

Population growth is a constant factor making all of these problems worse. The rise in the number of humans was until recently considered to be the greatest of all successes because it signaled more and more effective ways to combat death by starvation and disease. Larger, healthier populations were the most convincing argument for taking everything the axemakers offered.

However, today the human race crowds in ever larger groups. Mexico City has grown six fold since 1950, and Calcutta has more than doubled. By 2025 there will be 486 cities in the Third World with populations greater than 1million – with none of them capable of providing for adequate water, sewage, or garbage disposal. 100 million people on the planet today are homeless, 490 million are severely malnourished, and 360 million have no jobs. Population forecasts are catastrophic because even if the world’s birth rates have indeed slowed in recent years, the one billion humans still under fifteen years old who will grow up and have children means that the population will likely reach 11 billion by the year 2060.

Forward to the Past

The future faces us with serious difficulties we have inherited from the distant past. Humanity is no longer made up of a few scattered bands of people spread out thinly on the planet. Because our lives have changed since those primeval times, it is imperative above all that we revise our out-of-date perception of the world, so that our ancient, small-scale, small-time mind can be expanded to consider more distant horizons and more frequent changes. And we have been mentally so separated from the natural world around us by the axemaker gifts that both the gifts themselves as well as a change of consciousness need to be parts of the resolution. We are not in a position to throw away all modern technology and return to a simpler, Arcadian life, if such a world ever existed.

There is a gift which may help. It may change our mind back to where it was before the axemakers’ gifts. Ironically, it is one of the axemakers’ latest gifts. It is the computer.

Herman Hollerith, working in Baltimore in 1888, adapted techniques in use in the textile industry to his work on the US census. He developed a technique for the automatic recording of census data using holes in paper. After the census was done, he took his work to some investors, and IBM was born.

In the few decades since its invention, the computer has brought change to almost every aspect of modern life and has made society so complex and interdependent as to make the old cut-and-control, reductionist way of thinking too hazardous to operate in its previously isolated and unaccountable way.The networking of computers began as a linking of North American radar stations- the “Dewline” defense system. This technology was then adapted to become the basis for an airline reservation system known as SABER. This new tool made air travel easier, dramatically changing the nature of business. The computer has also compounded its influence by developing faster than any other innovation in history, so it has also altered our time perception regarding how fast rates of change can themselves change. Computer power increased a trillion-fold between 1965 and 2015, and is still increasing.

In parallel with these developments have come innovations in communications technologies that have produced high-speed data networks, making information more generally accessible, and its physical location irrelevant. The US “Score” satellite demonstrated in 1958 that voice signals could be broadcast from an orbital transmitter. Networks of such satellites have enabled transnational corporations to centralize operations more easily than ever before. They have also enabled electronic fund transfers, which have undermined the ability of governments to impose effective exchange control regulations on these corporations. Such networks could make possible highly centralized social management because they could radically increase the manufacture of specialist knowledge to enable cut and control on an unprecedented scale.

This cut and control scenario has always depended on the control of information, and specialists to guard and use that information. Two developments may change this situation. First is the electronic “agent”, a software program that can act on behalf of the systems user to search for required data, manipulate that data, and extract the required information. The other is the “knowledge-base system”, or “expert system”. These systems work by simulating some aspects of human reasoning and deduction. Use of these technologies can give the “man in the street” the ability to extract, and to put to use, information which previously had been the exclusive domain of increasingly esoteric specialists and their societies.

We are currently stuck in short term thinking. An example is air pollution. The long term health costs of the pollution are many times greater than the short term costs of cleaning up the air. In Mexico City, 72 percent of children have brain-damaging lead quantities in their cortex. The limited brain development because of this will perpetuate the cycle of Third World misery.

How can we change the way we think in time? One possible tool for change is the information technology as related above. The other is our brain. Our adaptation to differing environments, diets, and jobs attests to the extraordinary flexibility of the human brain. New research points out how heavily our brains are molded by experience when we are young. This implies that if we do not like the ways our brains operate, we can change them.

The recent research also suggests that our brains do not naturally follow the step-by step syllogisms of Aristotle or reduce problems to their smallest parts in the manner of Descartes. Rather our thoughts flit back and forward across the cortex, in a manner analogous to the process of innovation itself. There seems to be an ‘arational’ element to our natural thought processes.

The reason that the new data-processing systems might bring radical change in our relationship with the axemakers and to the way they have always indirectly organized our society and our thoughts relates to how the brain works. The key lies in how the brain interacts with the ‘web’ of linked computers, communication devices, and information processors. The highly linked nature of the web mimics our brain structure, and allows non-specialists access to unprecedented levels of information. Because of the correspondences of the web to our brain structure, entry into this knowledge pool does not require specialist training.

Of course, the web of information has implications for control and privacy issues due to the extent at which personal information has been placed on it. But it also holds out the hope that truly democratic communication systems can come about. It should become more difficult to propagandize and exclude members of the general public from decision making processes.

The growth ideal has all along ignored the fundamental fact that there is a limit to the extent to which the environment can supply the resources for expansion and absorb its waste products. Historically, authorities, with confidence in the economies of scale, have taken for granted that small social structures are inefficient and have acted against them. The state has erased independent villages, outlawed local guilds, and finally provided all the centralized social services that had become necessary because the state had destroyed them at local level.

An alternative may lie in the political potential of the web. This may require a different attitude towards representative democracy – it may require direct, participatory democracy, based in small-scale communities. The information web, and electronic agents acting on behalf of the members of these communities, may make feasible the kind of debate and consensus needed to operate in this manner. Small communities such as these already exist – eco-villages in Sweden, worker-owned plywood companies in the Pacific Northwest, the solar-powered community of Davis California, Quaker meetings, and others. The key political virtue of smaller-scale, web-supported communities run by direct democracy is that they provide forums for debate lost to us since Greece.

The open social system made possible by small-community participatory democracy is also harder to subvert and control; the structure encourages participation and consensus, and the closer contact between these communities and their environment makes for greater awareness of the need for self-sustaining, non-polluting economies.

The kind of changes proposed here are complex and wide-ranging, but they may not require large amounts of time. The Western world dropped its birth rate in just a few years in response to economic problems, without government pressure. The Southwestern Indian state of Kerala may also provide a model for success in the developing world.

In the 1970s, planners found that Kerala had falling birth and infant mortality rates, average life expectancy was approaching seventy years, and most adults could read and write. These were very exceptional for a tropical region. A study done by the UN concluded that the changes which brought about this situation in Kerala resulted from societal changes in attitude to family size resulting from longer life expectation, reduction in infant and child mortality, and female education. These, in turn, stemmed from substantial government investment in health and education. These advances were also achieved without transitioning Kerala through an industrial phase.

The culture we live in, based on the sequential influence of language on thought and operating according to the rationalist rules of Greek philosophy and reductionist practice, has wielded tremendous power. It has given us the wonders of the modern world on a plate. But is has also fostered beliefs that have tied us to centralized institutions and powerful individuals for centuries, which we must shuck off if we are to adapt to the world we’ve made: that unabated extraction of planetary resources is possible, that the most valuable members of society are specialists, that people cannot survive without leaders, that the body is mechanistic and can only be healed with knives and drugs, that there is only one superior truth, that the only important human abilities lie in the sequential and analytic mode of thought, and that the mind works like an axemaker’s gift.

Our survival may depend on the realization and expression of humanity’s immense diversity. Only if we use what may be the ultimate of the many axemaker’s gifts – the coming information systems – to nurture this individual and cultural diversity, and only if we celebrate our differences rather than suppressing them, will we stand a chance of harnessing the wealth of human talent that has been ignored for millennia and that is now eager, all around the world, to be released.

About the Book’s Authors:

James Burke is an author, educator, and award-winning television host best known for this successful PBS series Connections. The companion books to this and several of his other series, including The Day the Universe Changed, have been best-sellers in the United States and abroad.

Robert Ornstein was the author of more than twenty books, among them New World, New Mind, The Right Mind, The Evolution of Consciousness, and the best-selling The Psychology of Consciousness, now in its 4th edition. His final book, which he considered his most important, was the groundbreaking God 4.0: On the Nature of Higher Consciousness and the Experience Called “God.” He was the founder of the Institute for the Study of Human Knowledge, which is responsible for this Human Journey website. (See also: www.robertornstein.com.)

In the series: Evolutionary Perspective

- Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States

- The Axemakers Gift: Technology’s Capture and Control of Our Minds and Culture

- Guns, Germs, and Steel The Fates of Human Societies

- 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus

- 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created