Greece:

The European Axial Age

Something extraordinary in the history of humanity occurred 2,500 years ago in Athens—much of our cultural heritage descends from a very small population of landowners, farmers and sailors during a surprisingly short space of time. They organized themselves into a radically democratic government. They held as a high ideal the dignity and freedom of an individual free man. They produced sculpture and architecture which set the standards by which these arts are still measured, and they laid the foundations of our philosophy, mathematics and sciences.

Stepping from a plane in Memphis in 1968, Robert Kennedy was informed that Martin Luther King had been assassinated. In an impromptu moment that has become famous, he responded:

“… My favorite poet was Aeschylus. He once wrote: ‘Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.’…. Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world.”

To come to an appreciation of our Greek heritage is in some way similar to a fish coming to an appreciation of water.

Students are often astonished when they read for the first time the literature of classical Athens. It seems so much more familiar than, say, Dante’s Inferno, although this was written almost 2,000 years later in a language much closer to our own. Greek plays were unlike anything the world had seen before. They are gory, horrific, passionate and heartbreaking, their characters display human nature at its best and at its worst.

Although it came to us via a circuitous route, it is the Greek method of thinking that the Western world has inherited. The rediscovery of Greek science and philosophy in Medieval Europe kindled the Renaissance. To come to an appreciation of our Greek heritage is in some way similar to a fish coming to an appreciation of water. How we study this legacy is itself a product of that legacy. We separate our search for knowledge into Greek categories, such as politics, philosophy, history, and the individual sciences. Even the words we use for these disciplines are typically taken from the words used by the Greeks—technology, economics, logic, even our word “school” taken from the Greek schole.

By the beginning of the sixth century BCE, Athens was disrupted by the same social unrest that had affected many of the polis (city-states). Farmers, many of whom were Hoplite soldiers, banded against the aristocrats and civil war seemed unavoidable. Additional tensions were caused by the lack of written laws. To the Greeks, justice as part of a cosmic order ruled even the gods, but, in fact, the aristocrats controlled the laws and could change them at will. In 594 BCE, the aristocrats tried to forestall the civil war by electing the poet Solon as Archon, with a mandate to reform the constitution.

Solon (638–558 BCE)

Solon was certainly one of the first Greek Axial Age thinkers we know of. He traveled widely in Greece, visiting Croesus in Lydia, and Thales in Miletus. Plutarch states that Solon was not an admirer of wealth in his Life of Solon, within his collection of biographies, Parallel Lives. He describes Solon as saying that “two men are alike wealthy, of whom one has much silver and gold and wide domains of wheat-bearing soil, horses and mules, while to the other only enough belongs.” Like Thales, he spent time in Egypt, where, according to Plato, he heard the story of Atlantis from Egyptian priests.

Solon told the Athenians that their unstable political situation could not be blamed on a divine cause but was the result of human selfishness. All citizens, he said, should accept responsibility for this dysnomia (disorder). In his view the solution lay in their hands, and only a collaborative political effort could restore eunomia—good order and stability. Eunomia was about balance. It meant that no one sector of society should dominate the others.

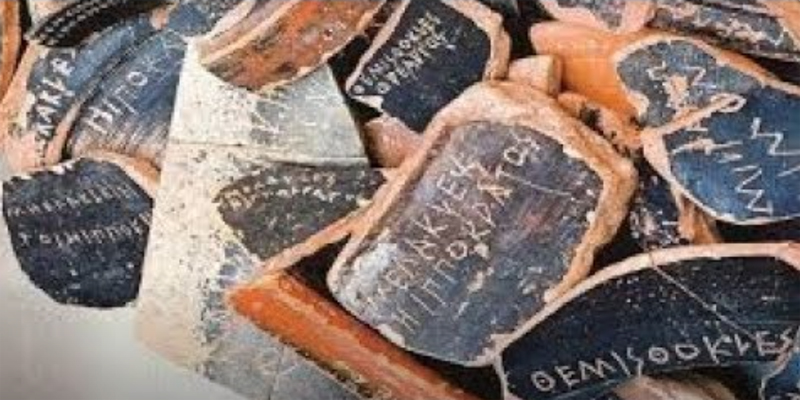

He set about reforms that strengthened the rule of law and set Athens on the road to democracy. For example, he abolished debts incurred mostly by farmers as well as debt slavery, and he formalized the rights and privileges of each class of Athenian society according to wealth. Wealth, not birth, would be the criterion for access to public office. He created a series of census ratings according to which each adult citizen would have his wealth recorded and thus have access to offices. Under Solon a comprehensive code of law was spelt out and made available on tablets, so that citizens could see how they were governed and what their rights were.

Under Solon a comprehensive code of law was spelt out and made available on tablets, so that citizens could see how they were governed and what their rights were.

Solon set a new standard as an ideal citizen when he refused to stay on to establish a tyranny in Athens to enforce these reforms: he had served the people without personal reward and as their equal. However, his reforms and ideas were not immediately accepted, and after his departure, Athens lapsed again into factional fighting and anarchy. Notwithstanding, the Greek world was impressed and put Athens at the forefront. In addition, the idea of eunomia would influence not only political development but the development of early Greek science and philosophy.

In 561 BCE, Pisistratus made his first attempt to become tyrant of Athens (a term that meant simply ambitious men who seized power), but this attempt failed. On his third attempt, fifteen years later, he entered Athens with not only his private army, but accompanied by a six-foot-tall Athenian girl representing the goddess Athena. This time he was successful.

Pisistratus maintained Solon’s laws and allowed elections to take place every year. Among his beneficial actions to Athens was the appointment of rural magistrates, enabling all farmers to have access to legal redress. His foreign policy added to the city’s prosperity, and he developed peaceful relations with other Greek tyrants. Pisistratus was responsible for the cultural transformation of Athens including the annexation of the island of Delos, which gave Athens control of the prestigious sanctuary of Apollo. He embarked on a building program that included the construction of a temple to Athena on the Acropolis and the temple of Olympian Zeus. He instituted competitive musical and athletic festivals such as the Dionysia and Panathenaia that made Athens an important cultural center of the Greek world.

Even though nobility still governed the city, the Council and People’s Assembly could now challenge any abuse of power.

From now on there is a strong sense of a government, rule of law and regularity in Athens, which leads the way to its eventual democratic development.

Pisistratus’s son Hippias ruled oppressively and was driven out of Athens with help from the Spartans, who then put a garrison of 700 soldiers in the Acropolis.

Cleisthenes drove them out and in one year in office (508–507), offered and gave democracy to the Athenian people. He completely reformed society, mixing people from different tribes and from the different factions of the Hill, the Shore and the Plain. He broke up old loyalties, redesigned and enlarged the Council and made the popular assembly the main legislative body. Even though nobility still governed the city, the Council and People’s Assembly could now challenge any abuse of power.

Voting in ancient Athens Greece. Learn more about Cleisthenes and Athenian democracy, how it worked and how democracy changed not only Athens, but the world.

“One has a sense as an Athenian citizen that you really can make a difference. There is no ‘us’ and ‘them,’ there is no government separate from the ordinary Athenian citizen body. They are the government. Democracy represented a sharp break where an originally elitist heroic culture was turned on its head and the idea was that even ordinary Greeks who weren’t aristocratic, who were not rich, could be as it were, heroes in politics.” —Paul Cartledge, the A. G. Leventis Professor of Greek Culture at the University of Cambridge, 2008–2014.

The Classical Period (Circa 500–300 BCE)

Athenian democracy became a model, and its reforms reverberated throughout the Greek world.

This new democracy unleashed a tremendous flourishing of culture resulting in a period sometimes described as “the Golden Age.” Yet it was a time of almost constant strife. It began in 490 BCE with the Persian Wars, which Athens was instrumental in winning, and it ended with the Peloponnesian War which pitted Athens and her allies against Sparta and her allies, and which Athens lost in 404 BCE. Yet in spite of, or perhaps because of, this turmoil, it was an extraordinarily creative time when Axial Greece came into its own, and the great monuments, the art, philosophy, architecture, democracy and literature that we now value as the beginnings of our own Western civilization came into existence.

During this time, Athenian democracy became a model, and its reforms reverberated throughout the Greek world. The middle classes now participated in council debates along with the nobles and Greek intelligentsia. A new system, which the Athenians called isonomia (equal order), now energized the Greeks and encouraged other polis to try similar experiments.

Athenians were now loyal to Athens above all and were committed to her survival and prosperity. They used their prestige and economic power to build a navy with which to fight Persia (490–479 BCE), and, when finally triumphant, they took command of a new alliance of Greek states and formed the Delian League in 478 BCE. Smaller allied states paid contributions in silver that enabled Athens to expand its shipbuilding and arsenals and led to Athenian domination of Greek trade.

Smaller allied states paid contributions in silver that enabled Athens to expand its shipbuilding and arsenals and led to Athenian domination of Greek trade.

Uncooperative states were seized, and their lands given to Athenian colonists (cleruchs). Thus, Athenian territory expanded. In addition, Athens became a haven for political exiles from other parts of Greece, people who brought their wealth and expertise, and who set up business ventures in the Athenian state.

Under Pericles (495–429 BCE) the authority of the Assembly and the Heliaea (people’s courts) was made absolute, the Parthenon, Prophylaea and Erectheum were constructed, and the Athenian Empire emerged.

Democracy and Slavery

Classical Greek democracy depended on the participation of the greatest number of citizens. Citizens had obligations to the state: to be part of judicial and political assemblies, to be on jury service, to attend religious festivals and other state activities. Even in their free time they were expected to play the prescribed part of the free citizen and to pursue activities called schole (from which we get our word “school”). Schole involved regular exercise at the gymnasium, attending philosophy lectures and poetry recitals, all of which helped to establish the free citizen’s superiority. In this way, the citizen proved himself fitted to rule.

Citizens were dependent upon the ubiquitous slaves. We know from the poems of Homer and Hesiod that slaves were part of Greek culture since the earliest times, before 700 BCE. In the later Classical period, even the poorest Athenian citizen would own a slave, and not owning one meant that you were practically destitute. Slaves provided invaluable wealth to the citizens and the state. They worked businesses and assisted the citizen women, who were virtually confined to their private homes yet in charge of domestic issues. They performed tasks for the State, including clerical jobs, removing refuse and dung from the streets, and dangerous tasks like silver mining in Laurium.

Greek democracy and culture depended on the ownership of slaves and Greek citizens found a way to justify it.

Ownership of land was still commended, and farming one of the most desirable sources of wealth, but the labor it required was not valued and where possible was performed by slaves.

In summary, Greek democracy and culture depended on the ownership of slaves, and Greek citizens found a way to justify it. The obligations of citizenship and the regular activities of schole—where the free man cultivated his mind, soul and physical capacity—proved his superiority. Conversely, those who labored and did not cultivate their mind were inferior. They were fit only for work and deserved to be slaves.