How Income Influences Our Health and Lives

Maternity ambulance, Uganda. Photo by Dave Proffer.

Our income level is a significant determinant of our health and wellbeing. People who have lower incomes tend to live shorter lives than the comparative fewer who don’t. They are also vulnerable to a host of risks and dangers because of their tenuous day-to-day subsistence.

“Before Covid-19, the fraction of the world’s population living in extreme poverty—meaning on less than $1.90 a day—had fallen below 10% from more than 35% in 1990. The pandemic not only halted but reversed that progress: since the onset of the health emergency to the end of 2022, the IMF estimated an additional 198 million people were likely to have entered the ranks of the extremely poor.” – Luca Ventura, Global Finance

In the book Factfulness and on Gapminder.org, Hans Rosling and his colleagues divided the world into 4 income levels based on projected daily income. Their Dollar Street project profiles individual families around the world at all four levels, helping us visualize the role of income in health and its determinants.

Poverty is the antithesis of health … eradicating it is critical to achieving good health for the globe and its population.

Over a billion people live at level 1, extreme poverty, on less than $2 dollars a day (or less than $704 per year). In general, these individuals live in simple housing constructions, say of mud or sticks. They use their bare feet as their major source of transportation, cook on an open fire, collect water in a bucket, sleep on the ground, have limited access to food and little variety in diet. Nearly 85% of their income is spent on food. As a result, they have little to save or to buy other essentials. Needless to say, health care is a rare commodity. The ten poorest countries in the world are currently all in Africa; South Sudan, Burundi, Central African Republic, Somalia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique, Niger, Malawi, Chad and Liberia.

In general, people in extreme poverty do not live as long as those in Level 4 (described below). They have bigger families and more children, higher death rates among children before the age of five, and are more likely not to receive any education. They are extremely vulnerable to illness, trauma, severe weather events and conflicts as a result of their tenuous day-to-day subsistence. They have limited or no health care, often due to poor transportation access to distant health clinics and no or limited ability to pay for those services.

At $29/month this family lives in extreme poverty. R is 28 years old and lives with his family in Burundi. He is a farmer as is his wife J who is 25 years old. They live with their daughter K, 2 years old, and their 3-month-old twin sons B and U. Together the couple works for 84 hours/week. The income usually depends on the number of times R works on the neighbors’ farms. The family lives in a single-bedroom home. They’ve been living there for the past 3 years. They built the house with the help of their family and friends. The house structure is weak with crumbling walls and leaking roofs. There is no electricity, and the toilet is outside the house and shared with other households. Even though they produce 99% of their food, nearly all of the family income is spent on buying the rest of the food supplies. Three times a week, R and J walk 40 minutes to get water. They also spend 14 hours a week collecting wood, which they use as fuel for their stove. The family saves very little money, since most of it is spent on food. Their favorite possession is the dried maize that hangs from the ceiling. They plan on buying a bed. They hope that one day they will be able to fulfil their dream of buying a house.

Approximately 4 billion people, the largest group, live at Level 2, getting by on $3 to $8 dollars a day. They might have some possessions like a bicycle, a mattress, or a gas canister for cooking at home, and they may be able to save up for sandals and send some of their children to school. They are still very poor and this additional $3-5 more per day provides little to cushion any disruption in their daily routine. Routine health care is out of reach. Nigeria, Bangladesh, India and Cambodia have many people living at Level 2.

The family lives in India. D is 57 years old and works as a farmer. His wife, K, is 45 years old and she looks after the house. They have 3 sons; G is 29 years old and works as an attendant, S is 26 years old and works as a labourer, and R is 24 years old and works as a farmer. The family lives in a 2-room house that they built and have been living here for 20 years. They own the house, in addition to another house and land. The house has electricity, but there are frequent interruptions in supply. They have drinking water in their yard, but there is no toilet. The family grows 80% of their food, while the rest is purchased or acquired as gifts. Food costs them nearly half of their income. They cook using either coal, propane or wood depending on availability. They spend 3 hours a week collecting firewood. The family is saving money and planning to buy a car. They hope one day to be able to fulfill their dream of buying a house.

Roughly 2 billion individuals live at Level 3, many in countries like China, Egypt, Rwanda and the Philippines. In Level 3, people live on anywhere from $9 to $32/day. They have running water, might own a motorbike or car, and their meals are a more rich and colorful mix of various foods from day to day. They may work multiple jobs and can save some of their income. They most likely have electricity and a refrigerator, which makes things like studying and eating enough varied nutrients easier.

About 1 billion people live at Level 4, on $32 a day or greater. Level 4 individuals might own a car or motorbike, live in a home with multiple rooms that they rent or buy, cook on an electric or gas stove, have water piped into their homes (both cold and hot), have access to more nutrients, and are more likely to have finished twelve years of school and have money to spend on leisure activities. At this level an extra $3 dollars a day makes very little difference to their daily life. In countries like the US, Canada and Great Britain and much of the Western world, the majority of people live at Level 4.

If you are reading this, you are more than likely at Level 4. Most people at Level 4 must struggle to grasp the reality of the 7+ billion other people in the world, particularly if they have always known this higher level of income: how tenuous life can be when a disability or a serious illness can throw you back to Level 1. We find it difficult to imagine how a measly addition of $3 dollars a day could possibly make a difference to someone living in extreme poverty and in fact move him or her into Level 2.

External Stories and Videos

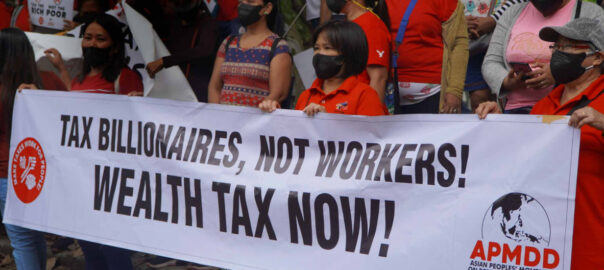

Survival of the Richest

Oxfam Briefing Paper, 2023

How we must tax the super-rich now to fight inequality.

Watch: Coronavirus Is Our Future

Alanna Shaikh, TEDx

Global health expert Alanna Shaikh talks about the current status of the 2019 nCov coronavirus outbreak and what this can teach us about the epidemics yet to come.

Watch: The Next Outbreak? We’re Not Ready

Bill Gates, TED

In 2014, the world avoided a global outbreak of Ebola, thanks to thousands of selfless health workers — plus, frankly, some very good luck. In hindsight, we know what we should have done better. Now’s the time to put all our good ideas into practice, from scenario planning to vaccine research to health worker training.

Watch: How We must Respond to the Coronavirus Pandemic

Bill Gates, Chris Anderson & Whitney Pennington Rogers, TED

Bill Gates offers insights into the COVID-19 pandemic, discussing why testing and self-isolation are essential, which medical advancements show promise and what it will take for the world to endure this crisis.

Sustainable Development Goals Progress Report

United Nations

A snapshot of global and regional trends towards the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals as of September 2019.

Dollar Street

Gapminder.org

Imagine the world as a street. All houses are lined up by income, the poor living to the left and the rich to the right. Everybody else somewhere in between. Where would you live? Would your life look different than your neighbors’ from other parts of the world, who share the same income level?

Maternal and Child Health

Childbirth can be a risky experience for women, especially in developing countries where 99% of all maternal deaths occur. Women in poorer countries are 27 times more at risk of dying from pregnancy, childbirth, or immediate post-partum complications than women in developed countries.

Current and Future Challenges

Deaths from diseases such as heart attacks, strokes, diabetes, and injury; the growing shortage of health workers; and the inevitable increase in population displacement all have an outsized impact on the poorest countries. What can be done?

The Status Syndrome

How Social Standing Affects Our Health and Longevity

Michael Marmot

In this seminal study, the renowned British epidemiologist Michael Marmot shows that the lower in a socioeconomic hierarchy a person is ranked, the worse is that person’s health—a maxim that holds for almost any disease or health risk factor. Those who stand higher up on the ladder of life are always healthier than those even a few steps below. It’s not poverty that makes the difference, says Marmot, but inequality—where one stands in the hierarchy.