Worldwide Water Shortage:

Water, Hard and Soft

The spillway of the dam in Oroville California collapsed after a period of unusually heavy rains in 2017

Mimicking the natural processes of the water cycle is a key component of this new “soft” direction.

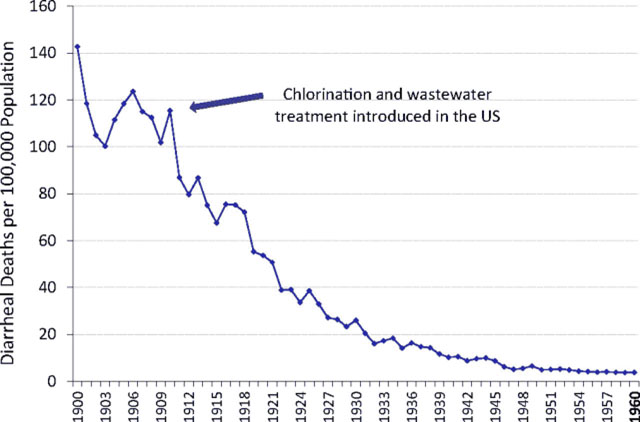

In the 20th century, massive dams, aqueducts, and centralized treatment plants dominated water planning. This infrastructure produced some of the most important developments in human history, notably a great reduction in water-related diseases and deaths. But negative consequences of this “hard” infrastructure have led us toward a new, “soft” approach. Mimicking the natural processes of the water cycle is a key component of this new “soft” direction.

Until a little over 100 years ago, cholera, dysentery, and typhoid fever claimed millions of lives each year, especially children’s. In the decades just before and after 1900 more than 20 million people in India alone died of cholera.

New methods of water management brought tremendous benefits to billions of people around the world. Damming wild rivers was the key development, allowing captured water to be sanitized and providing it safely, conveniently and inexpensively to far-distant homes and businesses. In addition to protecting public health, these massive infrastructure projects generated hydroelectricity, irrigated farmland and controlled floods, which were a common and often deadly occurrence.

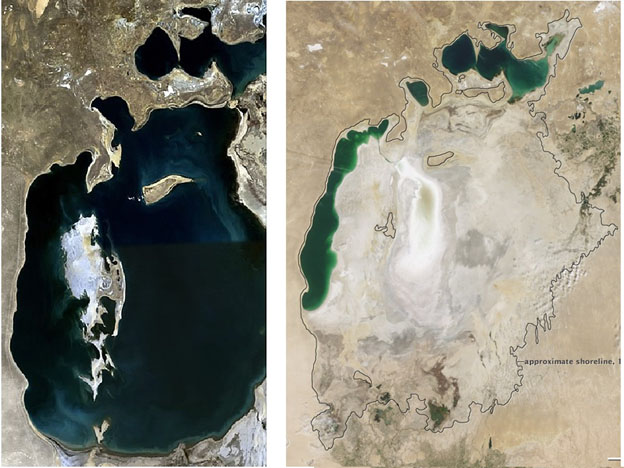

But this “hard path” to water management has also social and environmental costs. Tens of millions of people lost their homes. The flow of many of the world’s major rivers is now just a trickle by the time it reaches their delta outlets, damaging fisheries and drying up critically important habitat. More than one quarter of freshwater fish species are now threatened with extinction. Virtually all major rivers in the industrialized world are dammed. There are close to 100,000 dams in the US alone. Because new water sources are so limited and the harm from dams so extensive, water managers today advocate a “soft path” for water.

Natural soft-path water management methods include replenishing aquifers … and restoring watersheds that act as both reservoirs and cleaning systems for recycling groundwater.

Soft path methods stop wasting water and change the way it’s used. Prodded by regulations, many industries now routinely recycle their wastewater. Power plants recycle cooling water. Improvements in appliances have reduced household water use. Natural soft-path methods also include replenishing aquifers, many of which have been badly depleted during recent droughts, and restoring watersheds that act as both reservoirs and cleaning systems for recycling groundwater. If the same soft path savings can be applied to agriculture, the world’s shortage of drinking water will be solved. But it will take some convincing for many in industry and agriculture to accept that restoring a watershed can still provide the water they need.

Water, Water Everywhere …

All of the water in the world is recycled water – it is the same water brought to Earth billions of years ago by asteroid collisions. The seas are salty because rain is very slightly acidic, and over eons it dissolves rocks and washes the minerals into the ocean. Fresh water originates from evaporating sea water, falling as rain and snow onto land. Humans copy part of this cycle by recycling wastewater. Cleaning wastewater even to the point where it is safe to drink is a well-established technology. Israel, long faced with growing water shortages, recycles 85% of its treated wastewater. But Cape Town reuses just 5% of its treated water, and California only 15%. If more water were recycled, it could be used to recharge depleted aquifers – in other words, to save it for a not-so-rainy day.

Desalinization mimics another part of the water cycle by removing the salt from seawater. A few places like Kuwait, hot and dry but close to the sea, obtain almost all their drinking water this way. Desalinization either forces seawater through a membrane that allows freshwater to pass but blocks the dissolved salt, or else it boils seawater and condenses the fresh steam. In either case, problems include concentrated brine being pumped out as waste and great volumes of seawater being sucked in and killing large quantities of marine life. Although we are making progress addressing these problems, most people live where fresh water is plentiful—or used to be—and for them desalinization is a last resort because it uses much more energy and costs far more than drawing on local water sources.

Treating wastewater even to the point where it is safe to drink is a well-established technology.

On the other hand, the regions facing the greatest shortages, not surprisingly, have the hottest and sunniest climates. These water-stressed countries have high solar energy potential. Current desalinization is mostly fossil fuel-powered, but pairing desalinization with abundant solar power would provide virtually unlimited fresh water at very low cost. Yet the initial costs of construction are prohibitive for many affected countries, which span the range from highly developed economies, like Australia, to some of the least developed, like Yemen . Helping poor nations with this technology might benefit all because, again, cooperation will be essential to addressing these problems everywhere.

Does This Taste Funny to You?

The great benefits of 20th century hygienic water infrastructure are in danger.

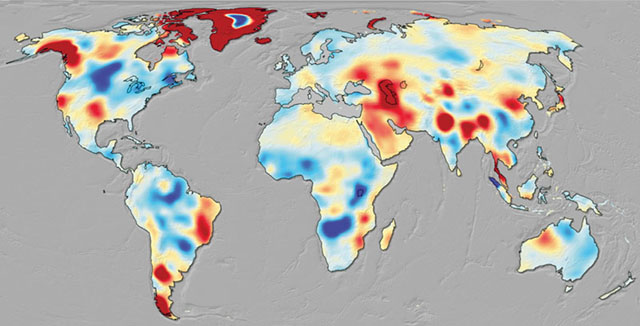

The warming climate is reducing the winter snowpack not just in the mountains of California but around the world. The headwaters of the largest rivers in Asia, which supply water to more than a billion people, are in the glaciers of the Himalaya. More than 80% of Himalayan glaciers are shrinking. But some regions have endured unprecedented rainfall producing epic floods, overwhelming drainage systems and dumping sewage into water sources. Toxic drainage flowing into shallow ocean waters has killed fish, fouled beaches, and repelled tourists from places where tourism is economically essential.

The great benefits of 20th century hygienic water infrastructure are in danger. Rising sea levels in coastal regions cause severe flooding that mixes sewage into drinking water. Even today more than one million people die each year from dysentery. Extreme droughts can force people to use whatever water is available. There is an ongoing cholera epidemic in Yemen, the site of the water crisis described earlier, that’s so dreadful that the United Nations has designated this the worst humanitarian crisis in the world. The availability of clean, fresh water is something we take for granted, but for many people this is about to change. And as always, it is the poorest who will suffer the most.

Nature Does Not Compromise

It is within our power to solve the shortage of drinking water. But too little drinking water is not the whole problem. As the planet warms, water will become scarce where it was plentiful and rare where it was scarce, adding to the widespread disruptions in the natural world. The effects are too numerous to list and will have many unforeseen consequences, but one example illustrates how these changes are interconnected. Drought and warming temperatures are killing the vast lodgepole pine forests of North America. The countless dead and dying trees standing in hot and dry conditions have erupted into the largest wildfires on record. The loss of the forest watershed is reducing the amount of water stored in aquifers, and so there is even less clean, fresh water in a region that is already experiencing drought.

What to Do

Take advantage of the many government and industry programs that subsidize low water-use appliances. If you are a homeowner or have a garden, adapt it so it relies less on irrigation. If it suits you, eat less beef. Perhaps the single best action to take is to stop buying drinking water in single-use plastic bottles, which not only transport water from far-away sources but also fill it with particles of microplastic. These actions will save you money, and perhaps also allow you to live longer as a result. Being a good citizen is not only good for the planet, it is good for you personally, too.

The Future

Six Drivers of Global Change

Al Gore

No period in global history resembles what humanity is about to experience. Explore the key global forces converging to create the complexity of change, our crisis of confidence in facing the options, and how we can take charge of our destiny.

Our Choice

A Plan to Solve the Climate Crisis

Al Gore

We clearly have the tools to solve the climate crisis. The only thing missing is collective will. We must understand the science of climate change and the ways we can better generate and use energy.

The Big Ratchet

How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis

Ruth DeFries

Human history can be viewed as a repeating spiral of ingenuity—ratchet (technological breakthrough), hatchet (resulting natural disaster), and pivot (inventing new solutions). Whether we can pivot effectively from the last Big Ratchet remains to be seen.

In the series: Not a Drop to Drink: Our Looming Global Water Crisis

Related articles:

Further Reading

External Stories and Videos

The world’s rivers are drying up from extreme weather. See how 6 look from space.

By Natalie Croker, Renée Rigdon, Judson Jones, Carlotta Dotto and Angela Dewan, CNN

The contrast in these rivers between 2021 and 2022 is alarming and starkly illustrates the growing effects of climate change.

Europe’s drought on course to be worst for 500 years, European Union agency warns

This year is set to be even worse than in 2018, when unusually favourable conditions in some parts of the bloc protected it from drought elsewhere, and the worst since the sixteenth century, a senior scientist working on the European Commission’s drought data warns.

The Lost River: Mexicans fight for mighty waterway taken by the US

Nina Lakhani, The Guardian

The Colorado traverses seven US states, watering cities and farmland. Before reaching Mexico, the river is dammed at the border, and on the other side the river channel is empty. Locals are now battling to bring it back to life.