Stepping Back from the Precipice

In recent years India has defied calls to abandon its aggressive plans to burn more coal. But now economics and a crisis in health have set the nation on a new course.

When the Agua Cliente solar plant west of Phoenix, Arizona was commissioned in 2014 it was the largest in world. But the new leader at Bhadla, India is ten times larger, and it will soon be eclipsed by another plant in Dholera which will be more than twice as large as that. These are just two of the fifty “Ultra Mega Solar Plants” being built in India, part of a new goal for the nation to more than triple electricity produced from renewable sources by 2030. India has sworn to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by more than one-third in the next few years and to achieve net-zero emissions by 2070.

(courtesy of Tata Power Solar)

This is a stunning change in government policy. Just recently India was the most aggressive country in its plans to burn more coal. These plans were so large and ambitious that even if all other countries in the world had immediately stopped producing greenhouse gases, India’s emissions alone would have pushed the climate beyond dangerous thresholds. Even so, the government claimed it had not only a right but a moral obligation to bring power to the hundreds of millions of its citizens living in the most appalling poverty. Burning coal was the cheapest way to accomplish this.

India has embraced renewable energy and especially solar power as its future.

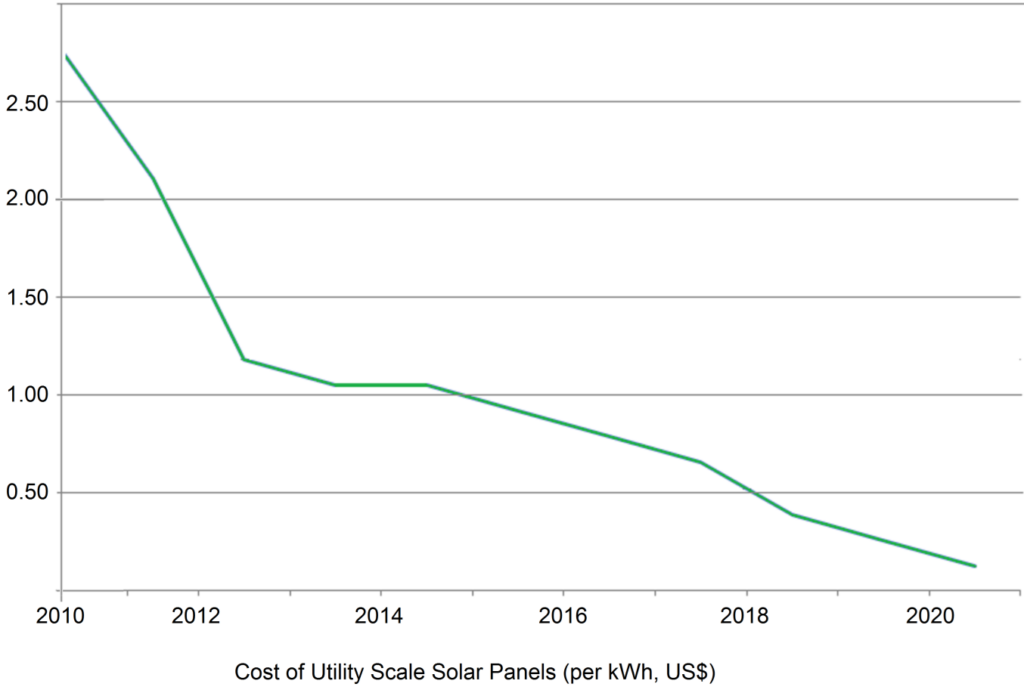

But the price of solar power fell more than 80% between 2010 and 2020, well below the cost of energy from coal. Now India has embraced renewable energy and especially solar power as its future. As a result, of the 16 Ultra Mega Coal Power Plants that were planned a few years ago, only two have become operational, two more are on hold, and the remaining twelve have been cancelled. In contrast, at least 34 of the 50 planned Ultra Mega Solar Plants have already been completed or have begun construction. But it isn’t only economics that led India to change its plans.

Killing with Kindness

Air pollution reduces the average Indian lifespan by more than six years.

For India’s poor, coal-fired electricity is no blessing. An article in the prestigious British medical journal Lancet estimates close to two million Indians die annually from air pollution. According to the World Health Organization, air pollution reduces the average Indian lifespan by more than six years—and by more than twelve years in the most polluted cities, where contamination can sometimes reach 200 times healthy limits. Death and illness due to mercury poisoning from coal mining are already common in rural villages, along with black lung and toxic drinking water. And on average, coal mine accidents claim an Indian life every week.

The problems facing India are shared by most of the developing world—the deep poverty that underlies the hopelessness and hostility in many resource-poor regions. But the opportunities offered by renewable power are also shared. It is true everywhere that the most suitable locations for renewable power are usually in regions where the land is agriculturally poor. Even in fertile Indian farming regions such as the Punjab, 15% of the land is unsuitable for agriculture—yet ideal for solar panels. So renewable power will improve living standards not only by providing electricity but also by creating good jobs in the areas most desperately in need of them.

Power Struggle

Solar power in India is now the cheapest in the world. Installing a new industrial solar panel in India costs about one third of the same installation in the US. Because of its tropical location, a panel in India will produce about three times as much energy per day as it would in northern Europe. From start to finish it usually takes 10 years for a new coal-fired plant to come online, while solar power projects can typically be completed in no more than a year and a half. India’s Central Electricity Authority now says that the country does not need any new coal-fired plants beyond those already under construction.

In general the industrialized world has been increasing energy efficiency and reducing emissions while developing countries have been moving in the opposite direction, usually by burning more coal. Burning coal still provides the greatest share of power in India. About 40% of India’s electricity comes from coal, consuming about 11% of the world’s coal production, second only to China. Although India is the second largest coal mining nation, it must still import coal. Since the beginning of this century India has more than doubled its greenhouse gas emissions.

India’s emissions are only 18% of the US total.

However, many in India believe that wealthy nations caused the climate crisis and are therefore responsible for fixing it. India’s emissions are only 18% of the US total. Per-capita, India ranks 35th in the world in coal consumption, after Laos. And India’s greenhouse gas emissions tell a similar story. India accounts for 7% of the world’s total emissions and is the third largest emitter—but its emissions per person are far below the world average. The industrial world became rich burning coal and is now telling India and other developing economies that they cannot do the same. But hurricanes, floods, drought and wildfires do not care who’s responsible for warming the Earth, in India or anywhere else.

What Is There to Lose?

Having tripled its solar power in the last five years, India plans to more than double solar capacity again by 2025.

India is at great risk from climate change. The monsoon rains that are critical for farming have become erratic, with violent downpours in some regions while others bake in drought. Millions of people starved to death when the monsoons failed many years ago. Since then, agricultural improvements have blunted the effects of crop failures. But there are limits to how much crop failure can be endured. India and its south Asian neighbors, in total one quarter of the world’s population, face competition for dwindling resources in this region where nations with nuclear weapons simmer in naked hostility.

Like China, India has found that cheap energy is the key to alleviating poverty but also that cheap energy from coal comes at a high cost to health and nature. Now India has discovered opportunity in the crisis. Having tripled its solar power in the last five years, India plans to more than double solar capacity again by 2025. India’s rapid growth in both its economy and its solar power is a model for how developing economies can decarbonize while still meeting their economic goals. And India will do this using the sunlight that falls within its own borders.

The Future

Six Drivers of Global Change

Al Gore

No period in global history resembles what humanity is about to experience. Explore the key global forces converging to create the complexity of change, our crisis of confidence in facing the options, and how we can take charge of our destiny.

Our Choice

A Plan to Solve the Climate Crisis

Al Gore

We clearly have the tools to solve the climate crisis. The only thing missing is collective will. We must understand the science of climate change and the ways we can better generate and use energy.

The Big Ratchet

How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis

Ruth DeFries

Human history can be viewed as a repeating spiral of ingenuity—ratchet (technological breakthrough), hatchet (resulting natural disaster), and pivot (inventing new solutions). Whether we can pivot effectively from the last Big Ratchet remains to be seen.

The Sixth Extinction

An Unnatural History

Elizabeth Kolbert

With all of Earth’s five mass extinctions, the climate changed faster than any species could adapt. The current extinction has the same random and rapid properties, but it’s unique in that it’s caused entirely by the actions of a single species—humans.

In the series: Our Climate Crisis

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

Watch: Digitalization & Energy: A new era in energy?

International Energy Agency

The IEA’s latest report, Digitalization & Energy, is the first-ever comprehensive effort to depict how digital technologies could transform the world’s energy systems.