Bonobos and Chimpanzees: Our Closest Living Relatives

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

About five and a half million years ago the human line of descent split from the ancestor we share with chimps and the lesser-known bonobos. 98.7% of our DNA is exactly the same as theirs, including some very basic traits often attributed only to humans. Are we more like the aggressive chimp or the peaceful bonobo?

Perhaps in part to justify the violence of our recent history, our human story has been most closely compared to the hierarchical and murderous behavior of chimps, which seems to have inspired the view of humans as aggressive by nature. The implication is that aggression is predominant in our makeup and there’s little we can do about it. But is this true?

Chimps have been known to science since the seventeenth century, whereas bonobos have been studied in the wild only since the 1970s and, because of political unrest, inconsistently at that. What if the situation were reversed? If we had known more about bonobos, might our view of ourselves be less about violence, warfare and male dominance—and more about empathy, caring, sexuality, peace, cooperation and, perhaps, even a matriarchal society?

Today, thanks to advances in science and technology—studies in animal and primate behavior on the one hand and in psychology and neuroscience on the other—we can at last begin to ascertain how much we inherit from our animal and primate past, and in what respects we differ. From there we can hopefully begin to understand our unique place and potential as human beings.

Are We Really More Like Chimps than Bonobos?

We share genes with all living things—even the banana and the fly! But most relevant to our starting point on this journey is to take a cursory look at the remaining primates closest to us.

While far more studies have been done on chimps than bonobos, it is important to note that neither one of these apes is genetically closer to us than the other. Chimps live across Africa in great numbers, whereas bonobos live only in the rain forests on the south bank of the Congo River, which permanently separates them from the chimpanzee and gorilla populations to the north. Just how different is their behavior?

“Bonobo behavior is hardly consistent with the popular image of our forefathers as bearded cavemen dragging women around by their hair.”

The social lives of chimps are complex. They are patriarchal, ambitious, excitable and violent. A male hierarchy with one “alpha” male at the top typifies the chimp community, though lower-ranking males often form coalitions to topple the reigning alpha male. These coalitions are the basis of their political struggles. Like us, they are more likely to help those who have helped them. Chimps band in aggressive groups to hunt down others often in bloody, brutal and fatal conflict.

As Frans de Waal suggests in his book Our Inner Ape: A Leading Primatologist Explains Why We Are Who We Are, our perception of the influence of our inherited behavior on our own history would likely have been far different if the situation had been reversed, and what we knew about ourselves and our inherited background came primarily from bonobos rather than chimps.

“Compared with the male-centered chimpanzee,” says de Waal, “the female-centered, erotic, and peaceable bonobo offers a fresh way of thinking about human ancestry. Its behavior is hardly consistent with the popular image of our forefathers as bearded cavemen dragging women around by their hair. Not that things were necessarily the other way around, but it is good to be clear on what we know and don’t know. Behavior doesn’t fossilize. This is why speculations about human prehistory are often based on what we know about other primates. Their behavior indicates the range of behavior our ancestors may have shown. And the more we learn about bonobos, the more this range expands.”

Bonobos and Humans Share Unique DNA for Bonding

DNA studies establish links that indicate some of our behavior comes from a time, around five to six million years ago, before humans split from our closest African ape relatives in the genus Pan. We share a particular piece of DNA with bonobos that is involved in affiliation and bonding, and is largely non-existent in chimps. Researchers at Yerkes Primate Center (Emory University) found that bonobos’ brains possessed more gray matter in areas that usually play an active role in identifying distress in social contexts, sensing distress in others and feeling anxiety. They also have larger connections between the brain’s amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex, suggesting a more emotional spin on resolving conflicts, and a better ability to control impulses than chimpanzees.

Bonobo society is matriarchal, egalitarian and mostly peaceful by nature: female bonobos form strong bonds with weak hierarchical tendencies; they rely on female coalitions to dominate the males in their group. While male bonobos are stronger individuals than females—up to five times stronger than the average human male—they do not form the male alliances that are observed in chimp groups but stay by their moms who do form alliances with other females and control the show. Sisterhood is power and female solidarity relies on an extensive network of alliances to assert collective dominance.

Recent studies have found that male bonobos are frequently aggressive, but that this almost always involves a single male attacking another male, whereas chimps tend to fight in gangs. And, unlike chimps, bonobos never fight to the point of murder. Dr. Mouginot and her colleagues, who carried out the research, noted that male bonobos may in fact benefit from attacking other males, since those who were most aggressive appeared to mate the most.

Although males and females collaborate in obtaining food mostly by foraging, bonobo females decide how food is shared among a group, and they and their young feed first. Bonobos’ food-rich habitat probably contributed to their social structure: since food is near at hand, they are able to stay together as a group and consequently create lifelong bonds. Gorillas and chimps cohabit in areas where food is sparser, so females have to go looking for food on their own.

Chimpanzee sex is for reproduction and males might kill another’s offspring as they compete for sexual favors from a potential mate. They need to know that their offspring survives and no one else’s. Bonobos are sensitive creatures and much of their frequent sexual activity is related to maintaining peace. They use sex to avoid violence—it’s hard to have sex and remain angry with your partner! Often casual and quick, sex, homosexual or heterosexual, is used for bonding, greeting, to settle arguments and for comfort. And, of course, by having multiple partners bonobos avoid infanticide—no one has any idea who their father is!

Much of their frequent sexual activity is related to maintaining peace.

Bonobos have a more upright skeleton, longer legs, and narrower shoulders than chimpanzees, and because of this, they have the ability to walk bipedally more easily and for longer amounts of time than chimpanzees. Their skeletal anatomy is not dissimilar to Australopithecines, early ancestors of humans. Their faces are flatter with a higher forehead than those of chimps, and their long black hair parts in the middle.

Some scientists feel that humans, chimpanzees, and bonobos are close enough to form a single genus

At the fundamental level we, in common with all creatures, seek the greatest possible genetic representation in the next generation: survival of ourselves is paramount for all species, and individuals strive to perpetuate their own genetic heritage to that end. Our abilities, societies and cultures reflect the same basic goal: survival. It’s not surprising that we share elements of these with both of our nearest relatives.

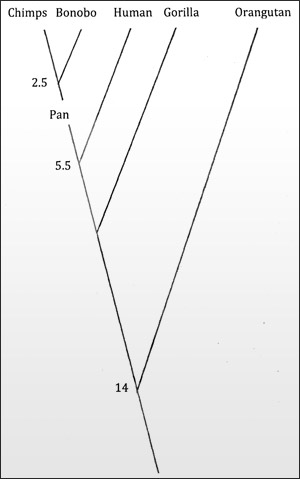

“Tree of origin of humans and the four great apes based on DNA comparisons. Data points indicate how many millions of years ago species diverged. Chimpanzees and bonobos form a single genus: Pan. The human lineage diverged from the Pan ancestor about 5.5 million years ago. Some scientists feel that humans, chimpanzees, and bonobos are close enough to form a single genus: Homo. Since bonobos and chimpanzees split from each other after they split from us, about 2.5 million years ago, both are equally close to us. The gorilla diverged earlier, hence it is more distant from us, as is the only Asian great ape, the orangutan.”

Our Inner Ape: A Leading Primatologist Explains Why We Are Who We Are, Frans de Waal

External Stories and Videos

In the Bonobo World, Female Camaraderie Prevails

Natalie Angier, New York Times

Researchers found coalitions arose when a senior female would step in and take the side of a younger peer caught up in an escalating conflict with a resident male.

Chimps May Be Able to Comprehend the Minds of Others

Catherine Caruso, Scientific American

A gorilla-suit experiment reveals our closest animal relatives may possess “theory of mind”