What AI Can’t and Shouldn’t Replace

Ella Jane Mortensen | June 12, 2025

As the use of artificial intelligence tools becomes more commonplace in everyday life, questions are being raised about what this new and continuously improving technology can do, and what it means for our future. While a large enough cohort of people view these developments with uncritical optimism (often those who work with or are enamored by technology), a great many others look upon AI with hesitation, some even with a sense of dread. I have frequently heard people say, almost jokingly, that “the robots are taking over” as they see AI tools popping into more and more elements of their digital lives. This statement reflects a deeper concern about AI as a potential threat to our humanity.

The fear of a technological takeover has been present in the mind of humanity ever since the early twentieth century, when it was expressed by the invention of the word “robot” by Czech playwright Karel Čapek. In his 1921 play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), he introduced an artificial humanoid worker designed to do unfavorable tasks. The robots, whose name comes from the Czech word robota, meaning forced labor, eventually rebel against their masters and develop a plot to destroy humankind:

Robots throughout the world, we command you to kill all mankind. Spare no man. Spare no woman. Save factories, railways, machinery, mines and raw materials. Destroy the rest. Then return to work. Work must not be stopped. (Čapek)

This story, despite its obscurity, will strike a chord with modern readers, as the theme of robots or artificial intelligence surpassing its intended limits has been repeated again and again in popular film and literature. This theme reflects humanity’s fears of the rapid technological changes our world has experienced over the last century. Yet these stories do more than just echo the feelings of a culture, they help create and define our reality by influencing how we think about our world.

Today, artificial intelligence is not just a science fiction trope, but also a real tool that anyone with an internet connection can access. Therefore, it is increasingly important to use discernment in the way we conceptualize this tool, and to not allow the fears and fictitious sci-fi representations of the past to define and limit our understanding of it. The term “artificial intelligence” misleads and frightens people into believing that AI is comparable to human intelligence, and might thus result in the creation of a competing race or tribe of beings that will turn on us in the future. Yet, there are also legitimate concerns about what effects this technology will have on our cultures and lives. If there is an overriding threat from AI (beyond making many of our jobs redundant), it may not be in the grand robotic takeover that we have been programmed to fear, but by way of a more gradual and subtle influencing of our minds and culture to operate more and more like the machines we have created. Though less violent and dramatic in the cinematic sense than a robot invasion, this remains a frightening outcome.

First, a quick, basic primer about AI. The thing we call “artificial intelligence” at the individual consumer level encompasses a broad range of tools with the capacity to perform tasks that normally require human mental skills, such as translating text, sorting and classifying information, summarization, and content generation. Today, the most accessible AI tools are dialogue-prompt systems such as ChatGPT, which presents a user-friendly interface and operates like a text messaging thread, appearing similar to a virtual conversation between friends. Ask one of these AI tools and it can create recipes, write essays, analyze homework, or reword an email. The rapid, detailed, and human-like responses that these systems generate can seem eerie to those users who are new to the technology.

Here is an example where I prompted ChatGPT to write a haiku. The results do not reflect a specific truth or experience, but the system’s mimicking of what a human might write.

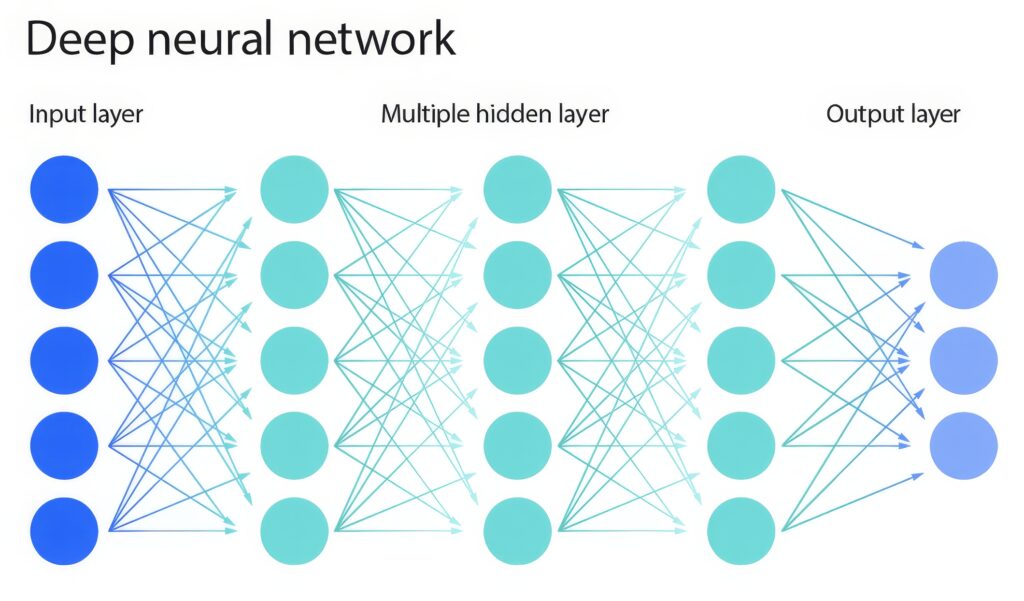

The above “poem” is essentially an average of averages of averages. Generative AI tools like this one are based on deep machine learning neural networks, which operate by predicting words to generate the most likely response to a prompt. These models are not manually programmed, but “trained” on incredibly large sets of data. They then “learn” to identify the connections between words and concepts to be able to make predictions about which words should come in a sequence.

Because machine learning neural networks are based on the way we understand our own brains in a very superficial, linear, and mechanistic sense, they will only ever possess these computational attributes. Natural human intelligence is much more complex and harder to capture—relying on the ability to view things not just in a rational and logic-based way, but also in a broader and more intuitive sense to create a complete picture. These two distinct elements to human consciousness are found primarily in the left and right hemispheres of the brain, which evolved to operate in tandem.

Understanding the differences between the hemispheres can help us to explore the difference between human and machine intelligence. The late American brain scientist Robert Ornstein describes these two modes of consciousness in many of his influential books, including The Psychology of Consciousness and God 4.0. So too does British scholar and psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist, in his two books The Master and His Emissary and The Matter with Things. The left hemisphere concerns itself with logical, linear, analytic, and detail-oriented tasks and tends to subdivide the world into separate parts. It does not see the big picture and is blind to context. The right hemisphere, by comparison, is emotionally and socially intelligent, receptive, intuitive, and is more concerned with a global and holistic picture of reality. In the human brain, these two modes contribute differently to various tasks, coming together to form a system that can adapt to varying circumstances. The left hemisphere is more machine-like in its perception and approach to the world, and is the nearest human analogue to not just the way AI functions, but also the inspiration for AI in the first place.

Iain McGilchrist has spent over the last decade arguing that our Western society is becoming excessively and dangerously left-brained. This is largely due to the materialist grasping and technological underpinnings of our culture. Left-hemisphere thinking has dominated the Western world, resulting in many advances in science, technology, and standards of living, but at the expense of other values and skills characterized by a more right-brain world view: deeper understanding, meaning, and an appreciation of context and the implicit. An even deeper and unchecked engagement with AI technology, an overreliance upon it, will likely habituate us further towards a left-brained perspective, much to our detriment.

But perhaps, like many things, the issue surrounding our use of AI comes down to one of degree. AI can be incredibly useful when applied responsibly, wielded with human hands and oversight as a tool that can help us fill current gaps and perform certain tasks better and faster. AI models are able to comb through sets of data and identify patterns that can help humans to use the information more effectively. AI is already being used to analyze weather and landscape patterns to predict natural disasters, and to accurately guess the shapes of proteins—helping us develop new medicines.

We should think carefully about what we delegate to the machines, and what we keep for the realms of human endeavor. In their book The Axemaker’s Gift, Robert Ornstein and James Burke remind us that the adoption of new tools and technologies has always come at a cost, “changing the way humans view their relationships to each other and to nature.” Whether it was the axe, the wheel, the printing press, or the car, these tools help us operate in the world with greater efficiency, while eliminating more basic skills, relationships, or engagements with the world that we used before that new technology came along. The car, for example, eliminated the need to walk and contributed to health problems, disconnection from the land, and urban spread.

As Silva Kantareva and John Bell write in “Reclaiming our Humanity in The Age of AI,” what we’ll give up for AI if we’re not careful is an essential degree of challenge and struggle in our pursuits which has a refining influence on our beings and defines us as humans. Therefore, we need to keep these systems as useful tools—and not more. Maintaining trust in human judgement is key to preventing them becoming insufficient replacements for our natural intelligence, as imperfect as it can be.

On a larger scale, we must not lose sight of that essence which separates the natural from the artificial—humans from our machines. This essential difference is found in the irrational, intuitive, and non-linear, rather than the logical and intellectual. It can be seen in the spontaneous play of a child, in the appreciation of the shifting and delicate ripple of long grasses in the wind, in that standstill instant of eye contact with an animal in the wild, and in the experience of creating a meaningful work of art. This essence is infinitely available: inside of us and in nature. If we are to accept the gifts of artificial intelligence and avoid the increasing mechanization of our culture and minds, we must insist on the primacy of our humanness as we struggle with how best to engage with these tools.

Ella Jane Mortensen holds a BA in international studies, specialising in global health, the environment and Europe, with a minor in philosophy. Her work experience includes tutoring, textbook editing and teaching English in Spain.

Recent Field Notes

- Proto-Indo-European: The World's Parent Language

- What AI Can't and Shouldn't Replace

- When Numbers Trick the Mind

- Community Health Workers: Bridging the Gap in Underserved Communities

- Building a More Playful World

- Bird Flu: Another Pandemic in the Making?

- Perception of Colors—and the Words We Use to Describe Them

- China's 2060 Carbon Neutrality Goal: An Unrealistic Dream?

- Tropical Cyclones in a Warming World