Homo Sapiens: The Hominid Survivor

From our beginnings in Africa, the story of human evolution is emerging as one of making contact and connecting.

The DNA of the remains of a boy found near Ballito Bay in KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa has shed new light on the transition from archaic to modern humans. The boy, of hunter-gatherer descent, lived in a time before migrants from northern Africa had reached South Africa’s shores.

Based on this boy’s genome and other ancient Stone Age hunter-gatherer genomes, the split from archaic hominids by modern humans appears to have occurred between 350,000 and 260,000 years ago. Fossils from anatomically modern humans, discovered on a desert hillside at Jebel Irhoud in Morocco, have been dated as 300,000 years old. Similar flint blades of about the same age as those found at this site have been found 20 miles south of Jebel Irhoud and at other sites across Africa.

This transition to Homo sapiens appears to have evolved at least 100,000 years earlier than previously thought and not exclusively in one part of the continent—East Africa, where hominid skulls and bones found near the Omo River in Ethiopia date to at least 195,000 years ago—but in several places, including southern and northern Africa.

Carina Schlebusch, a population geneticist at Uppsala University says “… both palaeo-anthropological and genetic evidence increasingly points to multiregional origins of anatomically modern humans in Africa. Homo sapiens … might have evolved from older forms in several places on the continent with gene flow between groups from different places.”

To add to the complexity, new DNA research hints at contributions to our genome from previously unknown sources, most likely humans who came back to Africa at some point before our immediate ancestor’s migration out of the continent. The correlation of climate simulation models with fossils discoveries indicates that from 125,000 years ago, every 20,000 years or so climate fluctuations triggered human migrations out of Africa, and some may well have returned.

Taken all together, as Chris Stringer points out, the origin of modern humans is much more complicated than previously envisioned. As he states in Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth, our understanding of this complexity will increase as more evidence is discovered.

At some point between 195,000 and 123,000 years ago, the population size of Homo sapiens plummeted, thanks to cold, dry climate conditions that left much of our ancestors’ African homeland uninhabitable. Africa’s southern coast appears to have been the refuge where H. sapiens survived these adverse conditions. Discoveries there confirm the idea that our advanced cognitive abilities evolved in Africa not Europe, and 50,000 years earlier than previously thought. These problem-solving abilities played a key role in the survival of the species during harsh times, and they would do so again in the Paleolithic period. “People were probably sharing symbolic material culture, at certain times but not at others,” says Dr Karen van Niekerk, a Universities of Bergen (UiB) researcher. It may well be that these cognitive developments evolved in response to necessity.

Meticulous excavations have been regularly carried out since 1997 at Blombos Cave at the southernmost coast of Africa. Work there uncovered what might be called “the first human workshop,” revealing a surprising level of collaboration early in our evolution. Christopher Henshilwood, from the Universities of Bergen & Witwatersrand, says, the Blombos site “serves as a benchmark during the early evolution of the cognitive abilities of Homo sapiens in Southern Africa.”

Ochre sites have been found dating to 200,000 years ago but, as Stringer points out, the preparation of red ochre in the form found at Blombos is a multi-step process involving a recipe for mixing the ingredients, then applying significant heat, and then storing the product. Three types of ochre were produced probably for painting, and toolkits appear to have been used more than once. Our ancestors collected, stored and worked with this soft clay, which is rich in iron oxide, and may well have had multiple uses, perhaps as a medicine, a coloring agent or sunscreen, or a kind of binder.

It is likely that the knowledge of this preparation was transmitted from generation to generation. Ochre was frequently used in early sites beyond the African continent by Paleolithic humans, including Neanderthals, as a pigment to mark their bodies for decoration and for designating social hierarchy, rites of passage, and other indications of cultural significance.

The gradual and uneven accumulation of cognitive developments over ca. 300,000 years indicates Homo sapiens’ ability to respond to climate fluctuations, and led to the cultural turning point which appeared in Europe during the Paleolithic period.

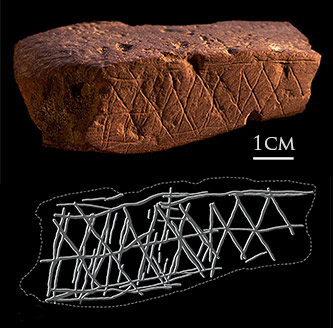

Artifacts at Blombos date from 100,000 to 75,000 years ago. They include shell beads and sophisticated tool-making abilities, such as silcrete bifacial points, probably used as spear heads, that were initially exposed to fire to increase their flaking ability. Although H. erectus’ shell tools with geometric engravings have been found that date to around 500,000 years ago, findings at Blombos and other sites in the region such as Klipdrift Shelter and Pinnacle Point show that the use of more complex abstract symbols, increased social organization, and an unprecedented degree of environmental adaptation occurred as early as 100,000 years ago. It pushes back the dates for sophisticated cognitive actions such as flint working, ritual behaviors and personal decoration by more than 50,000 years before the cave paintings of Upper Paleolithic Europe.

Seashells apparently drilled for use as jewelry, requiring skills previously associated with the technology of the Cro-Magnons, have also been found in the region. According to Henshilwood these “Shell beads and the engraving of designs, were likely used to signal information to other groups and to cement social relationships – perhaps shared access to resources, or a sense of identity. The ability to do this requires an understanding of abstract concepts and probably included the need for a well-developed language. This is unique to modern humans – and the evidence shows that this was most likely taking place ~100 000 years ago.”

Stringer feels that although the sophistication of the art and artifacts from Cro-Magnon Europe remains unprecedented, its foundation may have been similar to what underlay the Industrial Revolution or the Renaissance, in which the gradual and uneven accumulation of cognitive developments led finally to a cultural turning point.

“Evidence of symbolic thought (the transmission of coded information) and long range planning mark milestones in the evolution of Homo sapiens. The creation of paint, collection and manipulation of unique raw materials, and physical ornamentation are just some evidence that humans living ~100,000 years ago could conceptualize, create and store items for future use. It is these kinds of actions that are unique to modern humans and indicate that they were behaviorally modern, had enhanced cognitive abilities and social conventions and identities similar to humans living today. … Contact across groups, and population dynamics, makes it possible to adopt and adapt new technologies and culture and is what describes Homo sapiens. What we are seeing is the same pattern that shaped the people in Europe who created cave art many years later,” says Henshilwood.

Certainly, our ability to collaborate creatively in order to solve problems assured our survival during difficult times and prepared us for our journey out of Africa and into the modern world.

Interestingly, the human brain has become about 5–10% smaller during the past 20,000 years. As The Guardian science editor Hannah Devlin points out in the publication’s summary of human evolution, this brain size decrease may be comparable to the pattern seen in domestic animals, which almost always have smaller brains than their wild counterparts. She quotes Christopher Stringer: “Maybe we’ve domesticated ourselves and those bits of the brain that our ancestors needed aren’t so important anymore.”

Devlin says it is also possible that we are swapping individual brainpower for collective forms of intelligence. “Our brains are energetically very expensive – they use about 20% of our energy,” says Stringer. “So if evolution can get away with a smaller brain it will.”

The Gap

The Science of What Separates Us from Other Animals

Thomas Suddendorf

A leading research psychologist concludes that our abilities surpass those of animals because our minds evolved two overarching qualities.

Before the Dawn

Recovering the Lost History of Our Ancestors

Nicholas Wade, New York Times

New York Times science writer explores humanity’s origins as revealed by the latest genetic science.

In the series: Our Hominid Predecessors

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

Oldest Fossils of Homo Sapiens Found in Morocco, Altering History of Our Species

Carl Zimmer, The New York Times

New findings predate the previously oldest known fossils by more than 100,000 years and suggest that our species evolved in multiple locations across the African continent.