Homo Neanderthalensis: Built for the Cold

Both Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens could make fire, flaked stone tools, and clothing from animal skins. We know they lived side by side for more than 10,000 years. What became of them? Did they mate with Homo sapiens? Genome sequencing indicates they may live on in some of us.

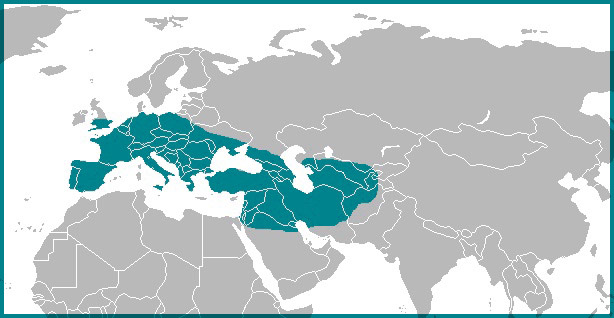

Groups of H. heidelbergensis who left Africa became isolated from one another more than 300,000 years ago. One group that migrated into western Asia and Europe are now known as Neanderthals.

Proto-Neanderthal traits are believed to have existed in Eurasia as early as 600,000-350,000 years ago, with the first “true Neanderthals” appearing between 200,000 and 250,000 years ago.

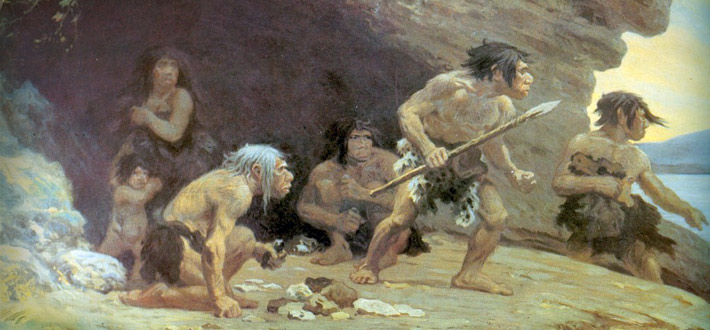

They were formidable, with brawny bodies built to conserve heat. They had comparatively short limbs, with a very distinctive craniofacial morphology relative to modern human populations: a large middle area of the face, and a big nose, which they needed for humidifying and warming the cold, dry air of the harsh, glacial conditions that existed then in Europe.

They were experienced hunters and foragers and knew how to develop weapons, such as stone-tipped thrusting spears. They also used wooden tools: two digging sticks 15 cm long have been found at Aranbaltza in the Basque Country coast of Northern Spain. These were made about 90,000 years ago from a yew trunk, cut longitudinally into two halves. One half was scraped with a stone-tool, then treated with fire to harden it and to facilitate scraping with a pointed tip. Analysis reveals that it was used for digging in search of food, flint, or simply to make holes in the ground.

Periods of favorable climate are thought to have drawn the Neanderthals down to the Levant.

About 100,000 years ago, at this southern edge of their European domain they met our ancestors, Homo sapiens, and prevented them from penetrating further into Europe, which Neanderthals had controlled for hundreds of millennia.

By the time the first H. sapiens arrived in Europe around 45,000 years ago, the Neanderthals had already established their own culture, Mousterian, which lasted some 200,000 years. Numerous flint tools, such as axes and spear points, have been associated with the Mousterian. These artifacts are typically found in rock shelters, such as the Riparo di Mezzena in Verona, Italy, and caves throughout Europe.

Most anthropologists now agree, based on evidence uncovered at 20 or so grave sites throughout Western Europe, that our closest evolutionary relatives intentionally buried their dead and cared for their sick and elderly at least some of the time. Evidence suggests that they decorated themselves with pigments and wore jewelry of shells and feathers. Most recently, a raven bone fragment found in Crimea appears to have been modified by Neanderthals intentionally to display a visually consistent pattern suggesting ornamental or symbolic use rather than mere butchery; and findings 336 meters deep in Bruniquel Cave indicate Neanderthals adequately mastered fire in order to construct an underground space which must have been for cultural or symbolic reasons, behaviors previously associated exclusively with modern humans.

Arriving H. sapiens found a landscape of forests and grasslands. Temperatures were cooler than they are today, and the northernmost regions were frigid, but overall the habitat was hospitable and game was plentiful. Around 40,000 years ago, temperatures fell, glaciers spread south, and the winter snow cover increased. The once-forested landscape became a cold, arid plain.

Both H. sapiens and H. neanderthalensis moved south, following mammoths, red deer, and other game, which were the staples of their meat-based diet.

Neanderthals were accustomed to hunting these large, dangerous animals from cover, dispatching them with hand-held weapons. This method of hunting was treacherous. The remains of almost every Neanderthal adult found so far show evidence of multiple broken bones and other serious injuries. They rarely lived beyond their 30s. Meanwhile, evidence indicates that their H. sapiens contemporaries, Cro-Magnons, initially weren’t doing any better.

But year by year, the territory of the modern humans expanded and that of the Neanderthals shrank. By 30,000 years ago, Neanderthals had disappeared from their last holdouts in the Iberian peninsula, from caves around Gibraltar, where they sought shelter from the worsening climate.

Both Neanderthals and Cro-Magnons could make fire, both made flaked stone tools, and both made clothing from fur and animal skins. These skills alone did not enable either to cope with the increasingly stressful environment, but the Cro-Magnons survived, and the Neanderthals did not.

What Became of Neanderthals?

Speculation about their extinction has often centered on modern humans killing them off or otherwise doing them harm (see for example, Jared Diamond’s The Third Chimpanzee). Chris Stringer, Research Leader in Human Origins at the Natural History Museum in London and author of Lone Survivors: How we Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth, points out that Neanderthals shared locations in Europe and the Near East with H. sapiens for much more than 10,000 years; although H. sapiens may have done away with some of them, he suggests that Neanderthal extinction must have included other factors.

Stringer speculates that, although its brain was larger than H. sapiens, the Neanderthal brain was optimized for controlling their greater physicality, including a bigger occipital lobe to process the visual data from their larger eyes. Though this adaptation most likely enabled them to see in the long, dark nights of freezing Europe, it left comparatively less room in their cerebrum for the frontal lobe, an area of the brain which is important for planning, and the parietal lobe, which is involved in communication.

Meanwhile, H. sapiens was adapting, stitching their clothing to retain more warmth while still preserving freedom of movement. Weapons like the throwing spear enabled them to hunt their prey from a distance. They learned to make fishing nets and snares to trap small mammals, and developed a diet that included fish, birds, and plants, rather than the meat of large and dangerous herd animals. This is the era when cave paintings, flutes, figurines and decorated artifacts of ivory and clay, some of exquisite beauty, first began to appear.

These adaptations were a leap toward modern cognitive abilities. This new cognition provided Cro-Magnons (early H. sapiens) with the advantages of more complex social organization. Large Cro-Magnon occupation sites have been discovered, and there is evidence they engaged in long-distance trade. Even though Neanderthal abilities have perhaps been underestimated, still they left no evidence of comparable talents or achievements.

Robin Dunbar of Oxford University writes, “They were very, very smart, but not quite in the same league as Homo sapiens. That difference might have been enough to tip the balance when things were beginning to get tough at the end of the last ice age.”

Luck of the Draw?

More recent research by Orin Kolodny and Marc Feldman of Stanford University suggests that no one factor—not a selective advantage in humans nor climate change—is enough to explain the demise of Neanderthals.

Using a computer simulation model based on known factors such as population sizes, migration patterns and basic principles of ecology, the team tested hundreds of thousands of variables reflecting what we don’t know. Almost every scenario had Neanderthals dying out within 12,000 years.

In the end, it would appear that Neanderthals were simply over-run and outlasted by the continuous flow of humans coming from Africa. Their fate—and in fact all of evolution—was more a matter of random chance, the accumulation of flukes of genetics and timing that stacked the deck in our favor. The two species were close enough in abilities and behavior that our fates could well have been reversed.

Did Our Ancestors Have Sex with Neanderthals?

It has been known for decades that H. sapiens and H. neanderthalensis lived side by side after the moderns arrived, in caves around Mt. Carmel in present day Israel and other locations. It has long been speculated that the two groups exchanged more than pleasantries.

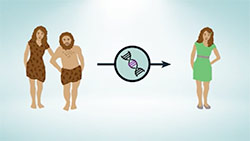

Confirmation that moderns interbred with both Neanderthals and Denisovans came from the Max Planck Institute. After sequencing the Neanderthal genome from remains found in Croatia, the team compared this with the genome of modern people from China, France, Africa, and New Guinea and found that all non-Africans today have as much as 4% of Neanderthal DNA in their genome and that the interbreeding happened soon after H. sapiens arrived in southwest Asia.

Genome sequencing from the DNA of five Neanderthals that lived between 39,000 and 47,000 years ago indicate that these late survivors were more similar to those that mated with our ancestors. From this research scientists were able to identify 10 to 20 percent more Neanderthal DNA in people living today than was possible when they were just relying on the Altai Neanderthal genome, the first Neanderthal genome sequenced.

By mating with Neanderthals we obtained some of their DNA: in Asians as much as 3% and in Europeans as much as 2%. These include three genes that are responsible for common allergies, for example, to dust, cats and hay fever.

“Neanderthals are not totally extinct. In some of us they live on, a little bit.” —Svante Pääbo

The Gap

The Science of What Separates Us from Other Animals

Thomas Suddendorf

A leading research psychologist concludes that our abilities surpass those of animals because our minds evolved two overarching qualities.

Before the Dawn

Recovering the Lost History of Our Ancestors

Nicholas Wade, New York Times

New York Times science writer explores humanity’s origins as revealed by the latest genetic science.

In the series: Our Hominid Predecessors

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

Mom was a Neanderthal. Dad was something else entirely. Meet the strangest hybrid in human history.

Sarah Kaplan, The Washington Post

A 90,000-year-old finger bone has been found belonging to a 13-year-old girl whose mother was a Neanderthal but whose father was a Denisovan.

Genome Sequencing Adds 5 New Neanderthals to the Human Family Tree

Sarah Sloat, Inverse

Now that later Neanderthal genes have been sequenced, scientists can identify between 10 – 20% more Neanderthal DNA in people living today compared with previously sequenced Neanderthal genomes.

Neanderthals—Not Modern Humans—Were First Artists on Earth, Experts Claim

Ian Sample, The Guardian

Neanderthals painted on cave walls in Spain 65,000 years ago – tens of thousands of years before modern humans arrived.

Searching for a Stone Age Odysseus

Andrew Lawler, Science

Finds over the past decade suggest that the urge to go to sea and the cognitive and technological means to do so predates modern humans and may have begun with Neanderthals thousands of years earlier than we thought.

Cave Structures Shed New Light on Neanderthals

CNRS

Broken stalagmites arranged in circles indicate that humans started occupying caves more than 100 millennia before previously thought and knew how to use fire to navigate dark spaces well before Homo Sapiens.

Neanderthals Defy Stereotypes

Evan Hadingham, PBS NOVA

Could a handful of stone tools coated with a sticky black substance conceal a vital clue to the mysterious Neanderthals? NOVA’s “Decoding Neanderthals” explores a surprising claim that these prehistoric people invented an artificial glue that required a complex manufacturing technique; in effect, that Neanderthals developed the first industrial process.

Did Our Ancestors Have Sex with Neanderthals?

Svante Pääbo, TED

Sharing the results of a massive, worldwide study, geneticist Svante Pääbo shows the DNA proof that early humans mated with Neanderthals after we moved out of Africa.

Ancestors of Modern Humans Interbred with Extinct Hominins, Study Finds

Carl Zimmer, New York Times

Interbreeding may have given modern humans genes that bolstered immunity to pathogens.