Greece:

Religious Life in the Greek Axial Age (Part 2): The Mystery Cults

Shrouded in secrecy, ancient mystery cults offered everyone—men, women, slaves and freemen—an opportunity to experience a more personal mystical religion, in which transcendence—or union with, rather than favor from, the divine was sought.

These mystery cults were often associated with a specific deity; they offered intense ritual experiences that represented the spiritual death and rebirth of the person. Only initiates could take part in the rites of a mystery cult, and they were forbidden to ever speak of what occurred. Participants followed this precept so faithfully that even today we know very little about what actually went on, though they have of course been the subject of much speculation.

The Orphic cult and the cult of the Egyptian goddess Isis both promised a way to a better afterlife. Isis was identified with Demeter in the Greek world, and Demeter and her daughter Persephone, often called Kore, were the focus of the most famous and popular of these mystery cults: the Eleusinian mysteries. This was an annual festival held at the sanctuary of Eleusis a few miles outside Athens. It would last for 10 days in late summer and centered on the worship of the goddess and her daughter. Initiates could be young or old, male or female, slaves or freemen. The only two requirements were that you spoke Greek and had not committed murder. At the height of its popularity thousands of people were initiated into its mysteries, took part in its rites and became mystai. Their numbers included many famous Greek philosophers and writers, including Plato and Plutarch.

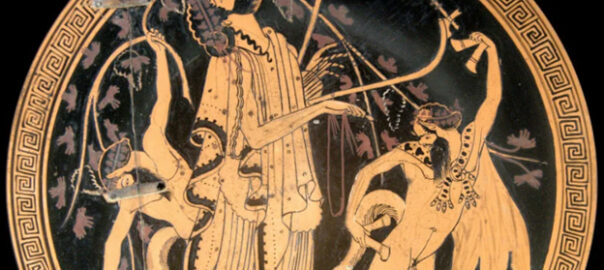

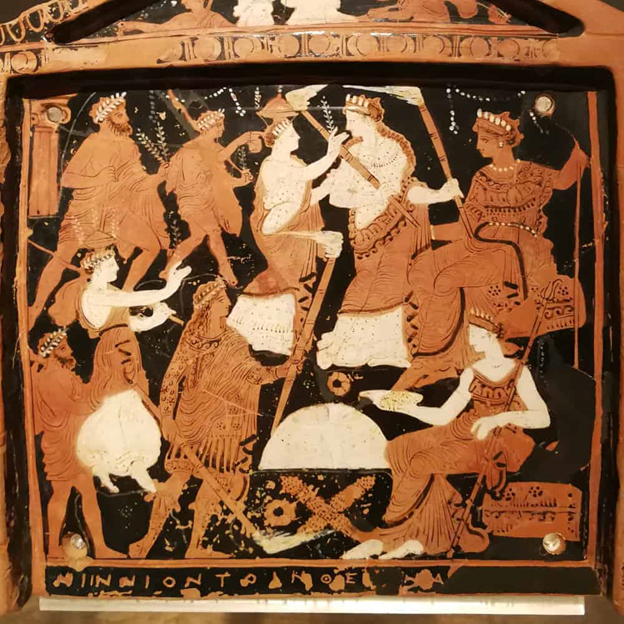

Initiates would trek in procession from Athens to Eleusis along the Sacred Way – the only road in central Greece until the Romans took power. Once there, they would perform secret rituals. Initiates would drink a beverage thought to have had psychoactive properties producing altered states of consciousness. They would go to the Telesterion (“the Initiation Hall”) that had a square roof that could cover as many as three thousand people. There they would recreate the Demeter myth. No one knows exactly what occurred during the rights as all initiates were sworn to secrecy under penalty of death. We do know that they would experience visions, dance, sing and make animal sacrifices, and we are told that initiates to this cult would come out radically different. They would claim to know what occurs after death; that death isn’t the end but a short time of darkness before a rebirth—like the myth of Persephone and the changing seasons.

The use of this sanctuary is thought to date from the Mycenaean Bronze Age c 1500 BCE. It survived until 392 CE, when it was closed under orders from the Christian emperor Theodosius 1. It was destroyed four years later by Christians determined to eradicate all evidence of pagan rituals, practice and sentiment.

The painted decorations are of immense complexity, showing human figures (on the left) approaching (much taller) deities to the right, perhaps at the end of the procession to Eleusis. The seated females ought to be Demeter and Persephone/Kore. Many motifs occur that we know to be connected to the Mysteries: lunar symbols, myrtle branches, torches, pottery vessels attached to the mortal women’s heads.

From the Encyclopedia Britannica:

“The cycle of the grain, pictured in the myth of Kore (Persephone), was thought to be parallel to the cycle of man. The myth, as told in the Homeric hymn to Demeter, tells how Hades (Pluto, or Pluton), god of the netherworld, wanted a wife and how he carried off Kore into the depths of the earth. Her mother, Demeter, through long days of searching, during which she came to Eleusis, refused to make the grain grow. Finally, Hades was bidden to send Kore back to earth. She came back to light as the grain maiden and gave birth to her son Plutus (Kore, ‘the maiden’; Pluton, ‘the rich one’; Plutus, ‘wealth,’ especially in grain). But, because Kore had eaten a pomegranate seed, a symbol of death and birth, she could not be completely released, and a compromise was reached by which she spent one-third of the year with her husband, the rest with her mother. Satisfied with this, Demeter caused grain to grow again and taught the Eleusinians her rites. The entire story of Demeter and Kore was elaborately reenacted in the Eleusinian ceremony. Just as in the myth Kore was carried away to marry Hades and to give birth to Plutus, so was grain thrown into the field and buried in the earth to bring forth new life. Just as grain came up out of the ground and was reaped to yield man’s bread and to be used as seed, so was a girl taken from her parents and her virginity ‘killed’ to bring forth new offspring. And when a man died, he was buried in the earth to partake mystically in the cyclic renewal of life. This was the message of Eleusis: out of every grave new life grows—for the initiates there are ‘good hopes’ for a glorious immortality in the afterlife.”