Proto-Indo-European: The World’s Parent Language

Hannah Mulcahy | July 7, 2025

It’s easy to spot how many similarities exist between languages in the same language family—many of the Romance languages share almost identical words for “water”: agua in Spanish, água in Portuguese and acqua in Italian. A slightly less obvious but still visible likeness can also be seen with the word apă in Romanian, also in the Romance language family. This connection (and many others) can very reliably be linked back to the Latin word aqua, which tells linguists that all of these languages must share Latin as a common ancestor. Words that derive from the same linguistic roots are called “cognates” and are incredibly helpful for identifying which languages have inherited words from the same parent language.

But what about the word “night,” for example? This word has many cognates across multiple, seemingly unrelated languages—we can see this in English: night, Russian: ночь (noch), Greek: νύχτα (nychta), Sanskrit: nisha, Welsh: nos and French: nuit. Why do these words sound so similar despite coming from completely different places? It turns out, all of these languages, as well as around 400 other living languages, belong to one huge umbrella group—the Indo-European language family. This language group can trace its roots all the way back to one original ancestor language, called Proto-Indo-European. The reason why words for “night” are so alike across so many languages is thanks to Proto-Indo-European’s original word for “night”: *nokʷt-, inherited by hundreds of languages.

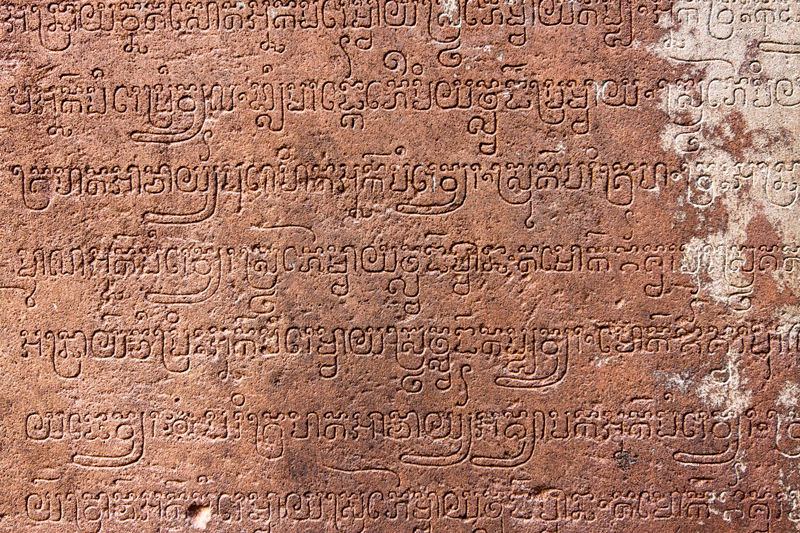

However, it’s not quite as simple as it looks. Unfortunately, there is no actual proof of Proto-Indo-European’s existence because it was spoken in a time of oral societies before words were written down, meaning that we cannot know with certainty what it really looked or sounded like. In order to better understand this language and its eventual branching out into its daughter languages, historical linguists have reconstructed Proto-Indo-European (proto meaning “original”, and in linguistics referring to a “reconstructed” ancestral language) into what they believe it would have been like when it was spoken thousands of years ago. Therefore, the word *nókʷt- (the asterisk denotes it is a reconstructed form) is simply a hypothesized reconstruction of the Proto-Indo-European word for “night” by modern experts; almost in the same way that paleontologists use the fossils of a long-dead dinosaur to imagine how it might have looked.

It may sound impossible to reconstruct a language that was never written down, but linguists have established a primary method which relies on evidence found in the descendants of Proto-Indo-European to reimagine the structures and sounds of their original parent language. This is called the comparative method and aims to identify cognates and correlations between various Indo-European languages, using these patterns to recreate what the original Proto-Indo-European structure would have looked like. While no one can know for sure what the original forms were, this method of reconstruction is regarded as a rigorous and credible approach and represents a significant milestone in the study and reconstruction of prehistoric languages.

Let’s look at the comparative method in practice. To reconstruct the Proto-Indo-European word for “foot,” for example, historical linguists would have started by identifying cognates across known descendants of Proto-Indo-European. They would have assembled a collection of words including Latin pes, Greek πούς (pous), and Sanskrit pada. Upon examination, it would have become clear that these words must derive from a common ancestor as their forms and meanings are too similar to be coincidental. Furthermore, when applying language laws like sound shifts (changes in pronunciation) to words for “foot” in other languages, even more cognates will come to light. The relevant sound shift for this particular cognate group is Grimm’s Law, which explains how, at some point in the development of the Germanic languages, the /p/ sound we see in Latin, Greek and Sanskrit shifted to an /f/ or /v/ sound. Understanding these sound shifts helps linguists follow how languages change over time and, as a consequence, makes it possible to track their lineage even if it’s not totally obvious anymore. Thankfully, for cognates of “foot,” a family resemblance to Latin, Greek and Sanskrit still exists across Germanic languages, for example; German Fuß (fuss), English foot, Dutch voet and Danish fod. By knowing about the laws of sound shifts and their effects on particular sounds, linguists have managed to recreate a robust sound system for Proto-Indo-European which has allowed them to reconstruct the Proto-Indo-European word for “foot” as *ped-.

The processes involved in the comparative method have been followed countless times to create a wide range of Proto-Indo-European vocabulary. The types of words that can be attributed to Proto-Indo-European tell us a lot about what speakers of this language discussed, allowing us to infer more about their culture. There are many Proto-Indo-European-derived words related to agriculture, such as words for “plowing,” “sowing,” “field,” “acre” and “barley.” Additionally, words for “cow,” “sheep,” “lamb” and “goat” signify that this civilization relied heavily on cattle raising. Words for “horse,” “ox,” “yoke” and “wheel” suggest that they drove carts as their mode of transport, making them one of the earliest civilizations to do so. Proto-Indo-European reconstruction has even revealed that they lived in a patriarchal society, with many words for a man’s family: “his father,” “his mother,” “his brother,” “his sister,” but no words to describe a woman’s family seem to be reconstructable. All of this information has also enabled historians and linguists to estimate a rough timeline of existence for this society: circa 4500–2500 BC.

The reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European has not only advanced the understanding of language development in the field of historical linguistics, but has opened the doors to an entire ancient civilization. The large collection of reconstructed vocabulary emphasizes the importance of linguistics from an anthropological perspective, showing how the study of the somewhat complicated and theoretical grammatical laws and sound shifts can actually be the foundation to uncovering cultural and social aspects of a forgotten society. What we know about Proto-Indo-European tells us that, despite evolving separately, cultures from around the world still echo the remains of a shared ancestry.

Hannah Mulcahy is a masters degree student in international development at the University of Sheffield in the UK. She holds an undergraduate degree in linguistics and modern languages, specializing in sociolinguistics, including language policy and language attitudes and perceptions, also from the University of Sheffield.

Recent Field Notes

- Proto-Indo-European: The World's Parent Language

- What AI Can't and Shouldn't Replace

- When Numbers Trick the Mind

- Community Health Workers: Bridging the Gap in Underserved Communities

- Building a More Playful World

- Bird Flu: Another Pandemic in the Making?

- Perception of Colors—and the Words We Use to Describe Them

- China's 2060 Carbon Neutrality Goal: An Unrealistic Dream?

- Tropical Cyclones in a Warming World