Muhammad: Origins of Islam:

Jahiliyyah, “The Time of Ignorance”

Despite an apparent code of chivalry (muruwah), by the end of the sixth century Arabs considered their own tribe first before anything, no matter what a tribe member had done. Their world was threatened by ubiquitous injustice, cheating, drunkenness, sexual immorality and cruelty of all kinds, including the maltreatment of orphans and female infanticide.

By the end of the sixth century the weakness of muruwah was apparent: each tribe had its own inherited rules, many of which led to reckless and extreme behavior. By this time, too, Yemen had become a province of Persia. With no hope of anything better, the Bedouin saw themselves in a life of struggle—relieved only by moments of pleasure, often taken in the oblivion of date wine—and constantly vulnerable to exploitation by the two empires. There was thought to be nothing wrong with stealing, injuring or murdering people outside one’s own tribe, so peace depended on a fragile stability created through alliances and affiliations between tribes. This depended more on the threat of retaliation and the comparative strength of each than on anything else.

One can imagine that many tribes’ members, especially the weak, the old, women and children, lived in constant terror. Chaos was spreading all over the Arab Peninsula. Incessant ghazu raids now led to what seemed to be a constant state of warfare between tribes, a condition that was exacerbated by unprecedented drought and famine.

With no hope of anything better, the Bedouin saw themselves in a life of struggle—relieved only by moments of pleasure, often taken in the oblivion of date wine—and constantly vulnerable to exploitation by the two empires.

A state of mind prevailed that the Prophet Muhammad called jahiliyyah, which, according to Karen Armstrong, translates as: “violent and explosive irascibility, arrogance, tribal chauvinism.” This same word would later be understood to mean the pre-Islamic historical period itself, translated as “The Time of Ignorance.”

The Quraysh had been in control of Mecca (Makkah) since the fourth century. Situated in the middle of the Hijaz, a region in the west of present-day Saudi Arabia, it had become a major commercial center at the crossroads of trade caravans linking Arabia with India, Persia, China, and Byzantium, and had its own Red Sea port at Shu‘ayba. Unlike other tribal settlements developed around water sources, Mecca’s stony infertile ground made agriculture impossible, so survival centered around commerce. During the last years of the sixth century the Quraysh had become extremely successful at this, but by the mid-seventh century ruthless capitalism had eroded their traditional egalitarian way of life. Quraysh society was now stratified, with its wealth confined to a few ruling families; the weaker, poorer, marginalized clans and individuals were left, lost and disoriented on the outside.

Pre-Islamic Religion on the Arabian Peninsula

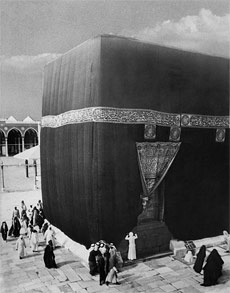

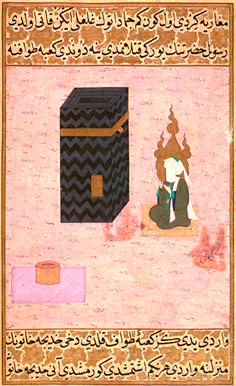

The peoples of Arabia were predominately polytheistic, and Mecca was the place of their most important sanctuary, the Ka’ba. Its ancient origins are unknown but, since all accessible deities were represented there, it was a place of annual pilgrimage for all tribes. At one time there were said to have been as many as three hundred and sixty idols in and around the Ka’ba. This, too, was under the control of the Quraysh, who wisely established a non-violent zone that was haram (sacred, forbidden), radiating for twenty miles around the sanctuary, and made Mecca a place where any tribe could enter without fear and where they were free to practice both religion and commerce.

The Ka’ba was the most important holy place in Arabia even in pre-Islamic times; it contained hundreds of idols representing Arabian tribal gods and other religious figures, including Abraham, Jesus and Mary. It is a massive cube believed to have been built by the Prophet Abraham – the ancestor to the Arabs through his first son Ishmael – and dedicated to al-Lah (The-God who is the same God worshipped by the Jews and Christians); it stands in the centre of the Sanctuary in the heart of Mecca. Embedded in the Ka’ba’s granite matrix is the famous Black Stone, which tradition says was originally cast down from Heaven as a sign for Adam.

The Ka’ba was the most important holy place in Arabia even in pre-Islamic times; it contained hundreds of idols representing Arabian tribal gods and other religious figures, including Abraham, Jesus and Mary.

The Zam-Zam holy well is nearby and is believed to have quenched the thirst of Hagar and her child, Ishmael, in the wilderness (Genesis 21:19). Arabs from all over the peninsula made an annual pilgrimage to Mecca, performing traditional rites over a period of several days.

Muhammad eventually destroyed all the idols in and around the Ka’ba, and re-dedicated it to the One God, Allah, and the annual pilgrimage became the hajj, the rite and duty of all Believers.

Barnaby Rogerson writes in The Prophet Muhammad: A Biography “The usual form of worship is for pilgrims to circle the Ka’ba seven times at a trot and then to drink from the holy spring. This rite seems to have a straightforward interpretation, with the square Ka’ba symbolizing the four corners of the earth which is circled seven times, just like the seven planets (or spheres of heaven) which were believed to circle the earth. We still live today in a yearly calendar ordered by these ancient beliefs, from the names and numbers of our days of the week, to the four weeks that form our lunar months and the stellar signs of the zodiacs.”

Like other pre-Axial societies, pre-Islamic Arab beliefs involved a pantheon of accessible deities with whom people could communicate. They also believed in darh, or fate, which probably helped them adapt to the high mortality rate. Above all of the lesser gods was the one remote God, al-Lah—the God who was the same God worshipped by the Jews and Christians. He was beyond the reach of ordinary people. Lesser deities were represented in the Ka’ba and in shrines to their individual honor scattered throughout the peninsula. These gods would be prayed to for rain, children, health and the like and would intercede on their behalf to Allah—the God in times of dire need.

This pre-Islamic attitude towards religion provided a framework that was open to ideas and interpretations. The Sasanian presence in the Arabian Peninsula had brought with it the influence of Zoroastrianism, in which Ahura Mazda and Ahriman, the Gods of Light and Darkness, were in constant battle for the souls of humanity. Jewish presence in the Arabian Peninsula appears also to date from as early as the Babylonian Exile and certainly from the time of the Great Revolt in 70 CE, almost six centuries before Muhammad.

Scholars note that a symbiotic relationship existed between the two peoples: Jews were Arabized and Arabic speaking and, over the centuries, Arabs had absorbed Jewish beliefs and practices. There were Jewish merchants and Jewish Bedouin, farmers, poets and warriors. What today is the center of Islam, the Ka’ba in Mecca, has ancient Semitic roots: Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses and others were associated with it long before the rise of Islam. Both Jews and Arabs were believed to be descendants of Abraham, an idol of whom could be viewed inside the pre-Islamic Ka’ba.

Since their earliest times Christian groups were established in Syria and Mesopotamia. In CE 313, the Emperor Constantine made Christianity legal and it became accepted as the imperial religion by Rome. The First Council of Nicaea in AD 325 declared Christ to be both fully God and fully man and established belief in the Trinity which represented God as three in one: the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Those who disagreed with this new orthodox position, Nestorians, Gnostics, and Arians for example, were excommunicated and declared heretics. Many fled from persecution, beyond the reach of the Byzantine Empire into the Persian and Arab worlds. Theirs was a proselytizing faith and as they spread throughout the Peninsula a number of tribes were converted. The Ghassanids, who wintered on the border of Byzantium, became the largest early Christian tribal community, the Nabateans another, and by the sixth century the Yemenite city of Najran was a center of Arab Christianity.

External Stories and Videos

The Legend of Hatim al Tai

Human Journey

This classic tale illustrates the Arab’s view of hospitality as a sacred duty and cardinal virtue—in this retelling the reader is also invited to reflect upon the real meaning of generosity.