Muhammad: Origins of Islam:

Judaism and Christianity in the Qur’an

“Islam, unlike any of its predecessors, insisted that truth became available to all peoples at specific times in their development; and that Islam, far from being a new religion, was no more and no less than the last in the chain of great religions addressed to the peoples of the world.” —Idries Shah, The Sufis

“In stating that there would be no prophet after Muhammad, Islam in its sociological sense reflected the human consciousness that the age of the rise of new theocratic systems was at an end. The events of the succeeding fifteen hundred years have shown this to be only too true. It is, for reasons of the development of society as we have it today, inconceivable that new religious teachers of the caliber of the founders of world religions should attain any prominence comparable to that achieved by Zoroaster, Buddha, Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad.” —Idries Shah, The Sufis

In his book The Islamic Jesus: How the King of the Jews Became a Prophet of the Muslims, Mustafa Akyol, a senior visiting fellow at the Freedom Project at Wellesley College, asks and answers a key question sometimes misunderstood by non-Muslims: “… who exactly was this one true God? The Qur’an’s answer is straightforward: the God of Abraham, Ishmael, Isaac, and Jacob. (Qur’an 2:132-133) Also, the God of Noah, Lot, Moses, Joseph, Job, Jonah, Elijah, David, and Solomon. All such figures, known in the Judeo-Christian tradition as Jewish patriarchs, prophets, and kings—along with only three Arab prophets, Shuaib, Saleh, and Hud—are honored in the Qur’an as the harbingers of a monotheistic tradition.”

The Qur’an maintains the unity of religions and the identical origin of each. It points out that monotheism is not a Jewish invention, but the archetypal religion proclaimed to many other nations by many other unidentified prophets: “. . . And there never was a people, without a warner having lived among them (in the past).” (Qur’an 35:24) So, not just the children of Israel and Muslims have been the receivers of divine guidance, but all people.

The Qur’an calls Jews and Christians “The People of the Book” and urges them to unite in Truth: “O People of the Book, let us arrive at a word that is common to us all: we worship God alone, we ascribe no partner to Him, and none of us takes others beside God as lords.” (Qur’an 3:64)

“O People of the Book, let us arrive at a word that is common to us all: we worship God alone, we ascribe no partner to Him, and none of us takes others beside God as lords.”

The singular and pivotal difference between Judaism and Islam is that the Qur’an states that their long-awaited Messiah has already come, and he is Jesus of Nazareth. And the singular and pivotal difference between Islam and Christianity is the latter’s belief in the doctrine of the Trinity, which holds that God is not one but three coeternal consubstantial persons, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit—“one God in three Divine Persons,” and that Jesus of Nazareth is that Son of God. The Qur’an strongly disagrees:

“People of the Book! Do not go to excess in your religion. Say nothing but the truth about God. The Messiah, Jesus son of Mary, was only the Messenger of God and His Word, which He cast into Mary, and a Spirit from Him. So have faith in God and His Messengers. Do not say, ‘Three.’ It is better that you stop. God is only One God. He is too Glorious to have a son. Everything in the heavens and in the earth belongs to Him. God suffices as a Guardian. The Messiah would never disdain to be a servant to God, nor would the angels near to Him.” (Qur’an 4:171-172)

As Akyol reminds us, “this theological tension between Islam and mainstream Christianity does not necessarily exist between Islam and the New Testament gospels. For in the gospels, Jesus is repeatedly called Son of God, but never God the Son.” According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, “Son of God” refers to “anyone whose piety has placed him in a filial relation to god.” Jesus seldom refers to himself as “Son of God” in these gospels, but more often as “Son of Man.” The same encyclopedia tells us that Son of Man “was not used as the specific title of the Messiah. The New Testament expression ὅ ὑιὸς τοῦ ἀνθρόπου is a translation of the Aramaic “bar nasha,” and as such could have been understood only as the substitute for a personal pronoun, or as emphasizing the human qualities of those to whom it is applied. That the term does not appear in any of the epistles ascribed to Paul is significant.” It goes on to confirm that in Ezekiel, Yahweh addresses the Prophet as the Son of Man about 90 times, and he certainly was human.

It was not until the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE that this core concept of the Christian faith, the Holy Trinity, was officially adopted and Jesus became the divine, literal “Only Begotten Son of God.”

Akyol continues: “we should note that the New Testament has various passages that define Jesus as a ‘servant of God,’ and that can only be music to Muslim ears. ‘Here is my servant whom I have chosen,’ Matthew (12:18) reads for Jesus, quoting Isaiah. Similarly, the Qur’an reads for Jesus: ‘He is only a servant on whom We bestowed Our blessing.’” (Qur’an 43:59)

The Gospels and the Qur’an agree that Jesus’s mission was not to found a new religion. The Qur’an describes Jesus as a messenger to the children of Israel, reviving, reforming and liberating the Jewish law. Muhammad’s mission was to bring this same fundamental message, reviving and reforming it to transform the consciousness of the Arab world and beyond.

The Qur’an acknowledges the role of the Jews in this chain of transmission, “O Children of Israel, remember the blessing I conferred on you, and that I preferred you over all other beings.” (Qur’an 2:47). “We sent down the Torah containing guidance and light, and the Prophets who had submitted themselves gave judgment by it for the Jews—as did their scholars and their rabbis—by what they had been allowed to preserve of God’s Book to which they were witnesses.” (Qur’an 5:44)

There are a number of similarities between the two traditions:

Islam and the Jewish Tradition

- The Qur’an resembles the Torah, which is also believed to be revealed by God, in that it tells us about God, His creation of the world in seven days, His laws and His prophets.

- The Prophets mentioned are all considered to be mortal human beings; none are the “son of God,” let alone God incarnate.

- Neither Judaism nor Islam have a doctrine of the Trinity, or anything like it, their monotheism is similarly strict and uncompromising.

- In both religions, the nature of God is unknown, and man can know God only by knowing his “attributes”—such as His justice, His mercy, and His majesty.

- Neither Judaism nor Islam recognize “saints,” who are, in Catholicism, intermediaries between God and men.

- Neither Judaism nor Islam accept the doctrine of original sin nor of redemption.

- Both religions have a strong tradition of religious law—Halakha in Judaism, Shariah in Islam. This law covers the rules of personal observance, such as dietary laws and dress codes.

- Neither eats pork or drinks wine.

- In both religions, male children are circumcised.

- The Prophet and his early Believers faced Jerusalem when they prayed three times a day. This direction of prayer, or qibla, changed in the fifteenth year of Muhammad’s prophecy, when a new revelation said that they should turn their faces to the Masjid al-Haram—the ka’ba.

- Mosques and synagogues are analogous temples: there is no graven image, no object of devotion such as the cross or statues.

“And We sent Jesus son of Mary following in their footsteps, confirming the Torah that came before him. We gave him the Gospel containing guidance and light, confirming the Torah that came before it, and as guidance and admonition for those who fear God.” (Qur’an 5:46).

Jesus and Mary, the Mother of Jesus, in the Qur’an

“… for if I go not away, the Comforter will not come unto you; but if I depart, I will send him unto you. … I have yet many things to say unto you, but ye cannot bear them now. Howbeit when he, the Spirit of truth, is come, he will guide you into all truth: for he shall not speak of himself; but whatsoever he shall hear, [that] shall he speak …”

To Muslims this passage from the Gospel of John (16:7-14) heralds the coming of Muhammad. In the Qur’an, we read that Jesus said: “Children of Israel, I am sent to you by God confirming the Torah that came before me and bringing good news of a messenger to follow me whose name will be Ahmad.” (Qur’an 61:6) The words Muhammad and Ahmad come from the same triconsonantal root H-M-D, or “praise.” Ahmad means “the Praised One,” Muhammad means “the most praised one.” Quite naturally to Muslims, Muhammad is the one “whose name will be praised” whereas Christians may well have interpreted John’s passage as referring to the coming of the Holy Spirit.

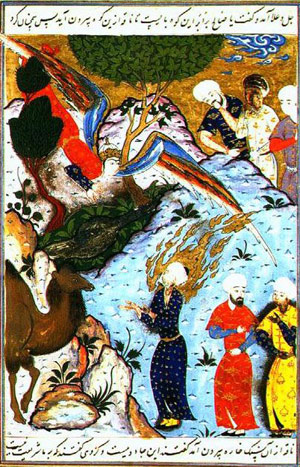

Jesus appears in some ninety-three verses in fifteen different chapters of the Qur’an, which emphatically declares that He is the Messiah. The term al-Masih is used eleven times and always refers to Jesus. He came to the Jews to reform the Law and with bayyinat or “clear signs”—miraculous abilities that are proof that prophets, like himself and Moses, have a divine mandate.

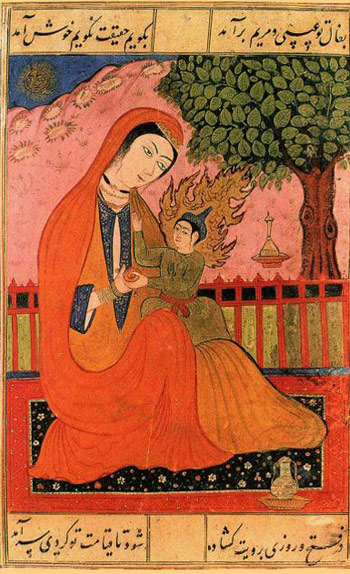

Mary, the mother of Jesus, is the only woman mentioned in the Qur’an. She was a virgin who conceived Jesus when God’s Spirit “breathed into her.” (Qur’an 34) Islam describes Mary as a woman “over all other women.” She is mentioned in the Qur’an 34 times, and only 19 times in the New Testament. There is a long chapter named after her in the Qur’an, and another after her family.

The Qur’an includes stories and miracles relating to Jesus, his work and life, and to Mary, his mother, that are not found in the New Testament but in apocryphal gospels, which were banned from the New Testament canon in the fourth century. For example, says Neal Robinson in Christ in Islam and Christianity, “The Protoevangelium of James mentions that as a child Mary received food from an angel, that when she was 12 a guardian was chosen for her by casting lots and that immediately before the annunciation she was occupied making a curtain for the temple. The Latin Gospel of Pseudo-Mathew includes the miracle of the palm tree and the stream but in the context of the flight into Egypt. … Jesus speaking in the cradle is mentioned in the Arabic Infancy Gospel. The miracle of creating birds from clay is found in the Infancy Story of Thomas.”

The Qur’an’s affirmation of the virgin birth presents another challenge to many Christians, who tend to couple this with Jesus’ divinity, but Islam does not. Separating these two ideas was not new at the time, as the church father Eusebius of Caesarea writes in Ecclesiastical History, 3.27, Chapter XXVII—The Heresy of the Ebionites, one of the Jewish-Christian communities, who, while they believed that Jesus was a prophet, “did not deny that the Lord was born of a virgin” but “refused to acknowledge that he pre-existed, being God, Word, and Wisdom.”

Although physical evidence is sparse, many scholars agree that the Christian ideas within the Qur’an must come from Jewish-Christianity. As the religious historian and philosopher Han-Joachim Schoeps says in Jewish Christianity: Factional Disputes in the Early Church: “Here is a paradox of world-historical proportions: Jewish Christianity indeed disappeared within the Christian church, but was preserved in Islam.”

Many Christian sects existed at the time of Muhammad within or near Arabia, communities like the Melkites, Arians and Nestorians—but these are described as “Pauline” since all believed that Jesus was in some sense divine—not just a human Messiah. The Ebionites (whose name means “the poor”) seem to have disappeared from the region by the end of the fourth century and none of their gospel survives.

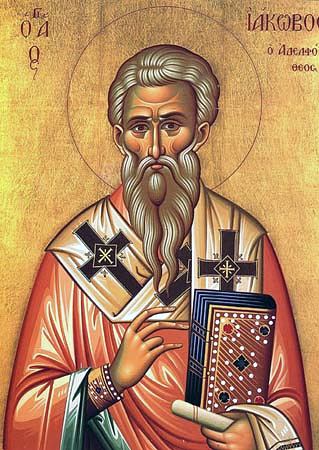

There is no mention of Paul in the Qur’an and its Christianity is certainly not Pauline. Paul, who unlike the apostles never met Jesus, nevertheless claimed a supernatural acquaintance with him, which gave him the authority to proselytize. Fueled by this conviction, he developed his own theology outside the “Jerusalem Church” which was led first by the brother of Jesus, James the Just.

Paul’s key ideas go directly against both Jewish Christianity and the Qur’an. His focus is not on Jesus the Jewish Messiah and his teachings, but on the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, insisting that “God presented Christ as a sacrifice of atonement, through the shedding of his blood.” (Romans 3:25 NIV) Christ died for our sins, and we are justified or covered by our faith in this.

In contrast, the Qur’an stipulates that “no bearer of burdens will bear the burden of another.” (35:18 and 53:38), and that “God requires not of anyone that which is beyond his capacity” (2:287). Nor does it share the theology of the Fall which made every human being inherently sinful and thus in need of a savior.

Like the Qu’ran, James the Just, Jesus’s brother and the leader of the early Jewish Christian community, strongly emphasizes works, rather than mere faith, as the basis of justification in the sight of God. “Ye see that by works a man is justified, and not only by faith. … For as the body apart from the spirit is dead, even so faith apart from works is dead.” (James 2:20-26 ASV)

As both Muslim and Christian scholars have noted, the Messiah in the Qur’an is no God, but he most definitely was an extraordinary mortal. The 14th-century scholar Nishapuri put it this way: “Jesus was specially favored, among all other prophets and saints by being called ‘word’ because he was created with the inherent capacity for this perfection.” Another Muslim scholar notes that his every word was a revelation by God. “Jesus was so open to divine inspiration, so responsive to the divine spirit, so obedient to God’s will, that God was able to act on earth in and through him,” wrote the theologian John Hick in “A Pluralistic View,” in Four Views on Salvation in a Pluralistic World. “This, I believe, is the true Christian doctrine of the incarnation.” As Akyol says: “that, I believe, is a doctrine of incarnation that Islam can wholeheartedly accept.”

In reviewing the history of this period, it becomes more and more evident that the disparity between Islam and Christianity began and grew as the latter moved away from the Middle East to settle and flourish in a polytheistic Gentile world. If Jewish Christianity rather than Pauline Christianity had flourished, the evolution of these three monotheistic traditions may well have been both gradual and transformative, and considerably more harmonious.

Above all it is important to realize that Muhammad was inspired by the Hanif, thinkers and seekers, who sought the ‘straight path’ of Truth, transmitted through teachers and prophets throughout human history.

Again, to quote Idries Shah’s seminal work, The Sufis, “It is this spirit and this claim to the essential unity of divine transmission which is what has been referred to as the ‘secret doctrine.’ Unless this feeling about the Qur’an is conveyed correctly, the inevitable conclusions about the limited clash between church Christianity and formal Islam becomes the only frame of reference for the scholar.” Or for anyone wishing to understand the evolution and purpose of religious thought.