Judaism:

The Jewish People

The story of the Jewish people traditionally begins about 1,800 BCE with the birth of Abraham (originally named Abram), whose insight was that the entire universe was the work of a single Creator.

The historian Karen Armstrong in her book The Great Transformation tells us that, although we know very few details, the collapse of Canaan at the end of the Bronze Age appears to have been very gradual. “The large city-states of the coastal plain, which had been part of the Egyptian empire since the fifteenth century, disintegrated one by one as Egypt withdrew—a process that could have taken over a century.” This left dispossessed peoples roaming the highlands of Canaan in search of employment and security. They eventually created a network of new settlements in the highlands, that stretched from the lower Galilee in the north to Beersheba in the south.

Centuries passed before anything formal was written down about the formation and birth of Israel. Then, in the sixth century BCE while exiled in Babylon, an elite group of poets, prophets, and priests would create, embellish, change, reinterpret and add to a narrative that would unify and inspire these disparate peoples, and account for their troubled past. To quote Armstrong: “The biblical writers were not attempting to write a scientifically accurate account that would satisfy a modern historian. They were searching for the meaning of existence. These were epic stories, national sagas that helped the people to create a distinct identity.”

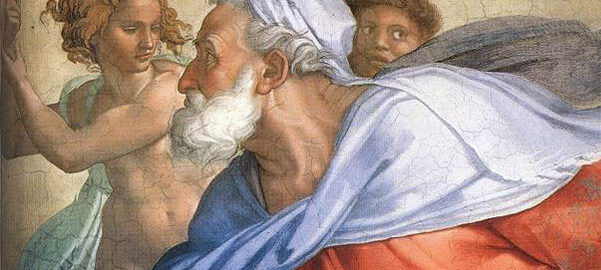

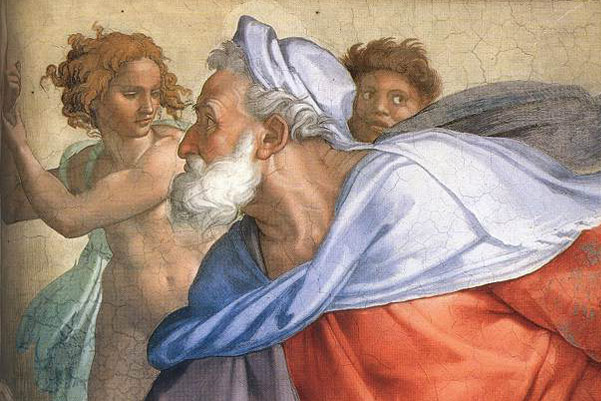

Their story would unify around an original ancestor, Abraham (Abram), who came from Ur in Mesopotamia, and who, at Yahweh’s (God’s) request, settled in Hebron in Canaan. In Genesis 12:1-3 we learn that God promised the patriarch that he would make Israel a mighty nation and give them the land of Canaan as their own. “I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and him who dishonors you I will curse; and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed.” (Genesis 12:1–3 ESV)

Strong words from the God with whom a comparatively small group of people would need to maintain a monotheistic relationship in a pantheistic world of competing gods and their more-established kingdoms.

Scholars draw mainly on three sources to reconstruct the history of ancient Israel—archaeological excavations, the Hebrew Bible and other ancient texts. An inscription on the victory stele of Pharaoh Mernepteh (c. 1210) mentions a military campaign in the Levant during which Merneptah “laid waste Israel” among other kingdoms and cities in the region. This is the earliest written reference we have. The Bible presents a problem as far as historical accuracy goes, mainly because it was never intended to be a literal history.

About 1250 BCE, a group of Canaanite refugees fled slavery in Egypt. The story of their Exodus bound the ancient Israelites together and is celebrated to this day at Passover. In their minds, their God had triumphed over the might of Egypt and allowed Moses to lead his people to safety. This traditional story tells us that Moses then receives God’s laws on Mount Sinai and brings them down to the people, only to find the Israelites worshipping a golden calf. Moses becomes angry and smashes the tablets on which the laws are written. Admonishing Israel, he returns to the mountain and obtains a new set of tablets which he gives to the people, placing them in the Ark of the Covenant for safekeeping. Thereafter, the Ten Commandments served as a sacred bond between the Israelites and their God.

The Hebrew Bible has several contradictory accounts of which laws the Israelites were given by God, how many they received, and where and when they got them. The version above was recorded at least six centuries later, during the Axial Age. Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman in their book The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts contend that these events most likely never happened: “…the Exodus narrative reached its final form around 650–550 BCE. Between 640 and 630 BCE the Assyrians withdrew from Canaan and were replaced by the Egyptians. It was Egyptian domination that was the basis for Exodus, which was really a story about the growing conflict between the Israelites and the Egyptians during the seventh century. Somehow those who wrote it projected the events back several centuries in time.”

Three centuries later civil war split Israel into two states, Israel and Judah, that collectively became known asam Yahweh—the people of God. Yahweh was their divine warrior, and these were warring times. But, as is typical of pre-Axial societies, the vast majority also turned to other gods for solutions to different problems. King Ahab, under the influence of Queen Jezebel, allowed Phoenician gods to infiltrate the land, especially the goddess Astarte and Ba’al, the god of harvests. In spite of the admonitions of prophets such as Elijah insisting on the exclusive worship of Yahweh, the Israelites would not become a monotheistic people until the height of their Axial period in the late 6th century BCE.