Symbolic Language

Image: Public Doman Pictures

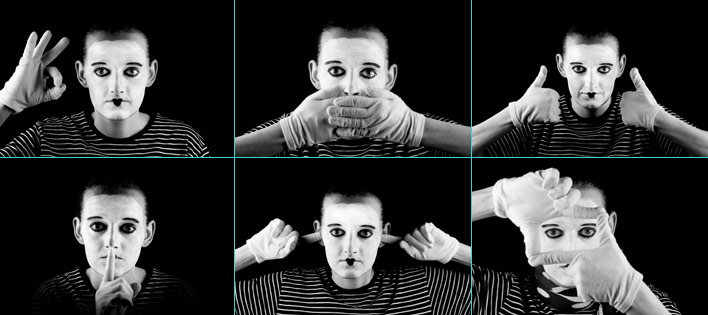

About 1.5 million years ago, Homo erectus began to use the symbolic language of pantomime to communicate. This enabled our ancestors to think about and to describe a past, present and future, and to pass on information and experience.

All primate brains contain neurons called mirror neurons that are activated in response to various actions, whether we make those actions ourselves or we see someone else perform those actions. It is one of the neural bases of connecting to others, and is also activated when we experience “symbolic” representations of actions such as in speech, mime, or reading.

Human beings have an unparalleled ability to recall memories at will and rehearse and refine those actions in our minds. This was a crucial precursor for the development of speech and language, and is still very much in use today. It underlies our rituals, games, sports and dance.

Unlike their sounds, great ape gestures can be intentional and responsive to the receiver’s state. Apes will follow where another ape (or human) is looking and understand that this is where attention needs to be directed. In his book, The Recursive Mind: The Origins of Human Language, Thought, and Civilization, psychologist Michael Corballis points out that gestures are likely to have been a very early precursor—dating from two to six million years ago – to our own ability to communicate with language.

In the 1980s the Italian scientist Giacomo Rizzolatti and his colleagues discovered a class of neurons which were activated in macaque monkeys in response to various actions. Additionally, they found that some of these same neurons were also activated when the primates saw someone else—monkey or human—perform those actions. These mirror neurons are now understood to be part of a mirror system we share with other primates.

“…the mirror-neuron region of the premotor cortex is activated not only when they watch movements of the foot, hand, and mouth, but also when [humans] read phrases pertaining to these movements.”

However, the mirror system in nonhuman primates differs in interesting ways from our own. Neurons in nonhuman primates are activated by the sounds caused by manual activity but not by vocal sounds. They respond to transitive acts, such as in reaching for an actual object, but do not respond to intransitive acts, where a movement is mimed and involves no object.

Writes Corballis, “In humans the mirror system involves characteristics that are more language-like than those in the monkey. …. [It] responds to both transitive and intransitive acts, and the incorporation of intransitive acts would have paved the way to the understanding of acts that are symbolic rather than object-related. More directly, though, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in humans shows that the mirror-neuron region of the premotor cortex is activated not only when they watch movements of the foot, hand, and mouth, but also when they read phrases pertaining to these movements. Somewhere along the line, the mirror system became interested in language.”

As social neuroscientist Matthew Lieberman puts it in Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect, our mirror systems provided a way for us to “share what we knew before we were able to say it out loud.”

Indeed, Homo erectus (beginning about 1.5 million years ago) made a qualitative break with other primate cultures when he began to use the most basic form of symbolic representation, pantomime or mimesis, to reenact events outside their immediate context. Mimesis undoubtedly included the same movements used for behavioral communication, but the difference came in using them apart from their real-life situations. For the first time our ancestors conceived that an idea or experience could be conveyed to another individual or group through its imitation or representation. If you think about this for bit, you’ll realize what an astounding cognitive leap this was! Skills like coordinated hunting and warfare, which already existed in hominids and other species, could be taught mimetically, away from actual risks and distractions. For the first time our early ancestors could think about and describe a past, a present and a future. To pass on understanding and experience in this way greatly improved their chances of survival and evolution.

With a sufficiently elaborate mimetic language, Homo erectus could create a culture that was intermediate between apes and modern humans. Our complex rules, social structures and highly cooperative forms of behavior—our rituals, games, sports and dance—all grew out of mimesis.

Our complex rules, social structures and highly cooperative forms of behavior—our rituals, games, sports and dance—all grew out of mimesis.

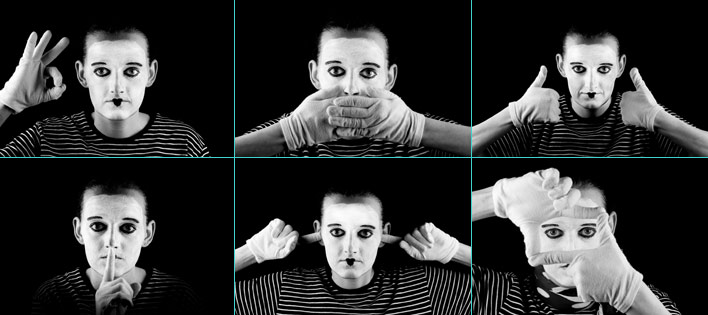

Mimesis is still very much in use today, particularly in our group behavior. Religious ceremonies and most sports events follow ritualistic rules of movement, action and dress, which are conveyed and reinforced mimetically. Each culture also has its own repertoire of hand and body gestures that accompany speech or stand on their own. Gestures like clapping your palm to your forehead, scratching your head while scrunching your face, or folding your arms across your chest while tightening your lips are all understood to have certain meanings. Chances are that nobody has ever explained these meanings to you, but you’ve learned them through observation. Actors rely on the common recognition of specific movements to convey a broader picture of their characters than words alone could deliver, and comic actors often use a conflict between mimetic and spoken meanings for humorous effect.

Mimesis stimulated our ability to memorize, as Merlin Donald explains in his book Origins of the Modern Mind: “Only humans can recall memories at will; and the most basic form of human recall is the self-triggered rehearsal of action, the refinement of action by purposive repetition…. the whole body becomes a potential source of conscious representation.” This voluntarily accessible memory system was a crucial precursor for the development of speech and language.

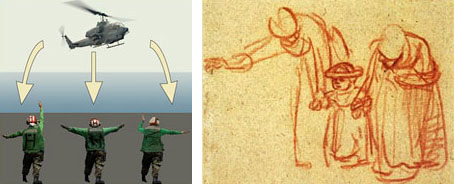

The First Word

The Search for the Origins of Language

Christine Kenneally

Human communication depends on the same genetic foundations as other animals. Some were born with a greater inclination to collaborate, forming the symbolic communication of language.

Numbers and the Making of Us

Counting and the Course of Human Cultures

Caleb Everett

Numbers, says Everett, are a key linguistic innovation that has distinguished our species and reshaped human experience.

In the series: The Evolution of Language

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

From Churchill to Libya: How the V Symbol Went Viral

Nathaniel Zelinsky, The Washington Post

The story of the V symbol spans cultures, time zones and decades. Its meaning has evolved, yet it is understood around the world as a symbol of resistance.