Our Brain’s Two Hemispheres

The lateral specialization of our brain’s two hemispheres not only enabled higher cognitive capacities for abstract thought, self-reflection and creativity; it also gave rise to a higher but embryonic cognitive ability, that we can consciously develop.

The content of this section, unless indicated, represents Robert Ornstein’s award-winning Psychology of Evolution Trilogy (God 4.0, The Evolution of Consciousness and The Psychology of Consciousness) and Multimind. It is reproduced here by kind permission of the Estate of Robert Ornstein.

As we’ve shown before, our language, reasoning – even our idea of morality – are scaffolded upon the biology of animals that preceded us on the evolutionary tree. This most recent evolution is no exception, our divided brain is built upon the lateralized specialization of earlier brain development. Studies in animal behavior, developmental psychology and neuroscience show that non-human animals have a rudimentary hemispheric specialization for various functions.

For us, however, this development not only enabled higher cognitive capacities for abstract thought, self-reflection and creativity; it also, and most importantly, gave rise to an inherent and embryonic cognitive ability, one that we can consciously develop. We will discuss this exciting finding, but first, a quick look at the overall functions of our two hemispheres.

The easiest and best way to think about the relationship between our brain’s two hemispheres is as one between the text (the literal statement itself, alone) and the context (the meaning, taking in all the information as a whole).

This means that while both hemispheres share the potential for many functions and both sides participate in most activities, in most of us the two hemispheres tend to specialize.

The left hemisphere (connected to the right side of the body) is predominantly involved with analytic, logical thinking, especially in verbal and mathematical functions. Its mode of operation is primarily linear. This hemisphere seems to process information sequentially. Since logic depends on sequence and order, this mode of operation must of necessity underlie logical thought. Language and mathematics, both primarily left-hemisphere activities, also depend predominantly on sequence.

If the left hemisphere is specialized for analysis, the right hemisphere (again, recall, controlling the left side of the body) seems specialized for synthesis. This hemisphere is primarily responsible for orientation in space, artistic endeavor, crafts, body image, recognition of faces. It processes information more diffusely than does the left hemisphere, and is responsible for the integration of many inputs at once.

Each hemisphere is a major one, depending on the mode of thought under consideration. If one is a wordsmith, a scientist, or a mathematician, damage to the left hemisphere may prove disastrous. If one is a musician, a craftsman, or an artist, damage to the left hemisphere often does not interfere with one’s capacity to create music, crafts, or arts, yet damage to the right hemisphere may well obliterate a career.

Split-Brain Studies

When Joseph Bogen surgically split the two hemispheres of the human brain (the famous “split-brain” operation), the patient’s ability to connect objects to a whole was gone in one side.

In the 1950–60s, Roger Sperry and Joseph Bogen led a research team which conducted the first split-brain study, investigating the effects on brain function of severing the corpus callosum – a bundle of nerve fibers that connects the left and right hemispheres of our brain. By disconnecting the two sides in this way, the team were able to study each hemisphere’s individual functions and interactions independently, without interference from the other hemisphere. What they discovered was both groundbreaking and transformative for our understanding of how the brain works.

Their studies showed that although each hemisphere shares the potential for many functions and both sides participate in most activities, in the normal person the two hemispheres tend to specialize. The left side of the brain controls the right side of the body, and vice versa. Anything that falls in the left visual field of each eye is projected to the right hemisphere and vice versa. And the left hemisphere is mainly, though not exclusively, in charge of language. But the hemispheric independence of a split-brain patient also revealed something puzzling about conscious experience.

After the surgery, if patients held an object such as a pencil, hidden from sight in the right hand, they could describe it verbally. However, if the object was in the left hand, they could not describe it at all. Recall that the left hand informs the right hemisphere, which has a limited capability for speech. With the corpus callosum severed, the verbal left hemisphere is no longer connected to the right hemisphere, which communicates largely with the left hand. Here, the verbal apparatus literally does not know what is in the left hand. Sometimes, however, patients were offered a set of objects out of sight, such as keys, books, pencils, and so on. They were asked to select the previous given object with the left hand. The patients chose correctly, although they still could not say verbally just what object they were taking. It was as if they were asked to perform an action and someone else was discussing it.

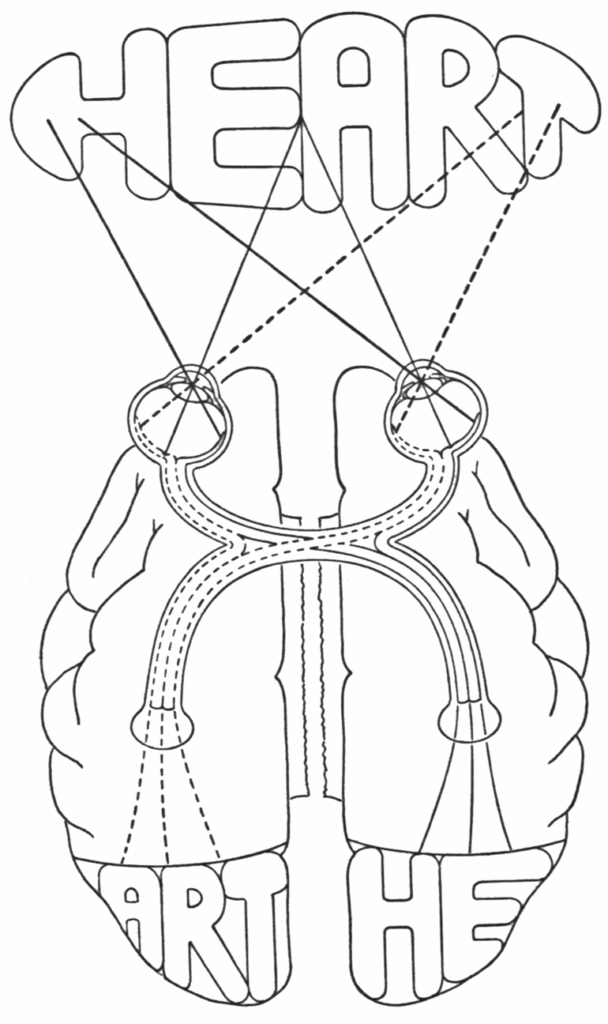

Another experiment tested the lateral specialization of the two hemispheres using split visual input. The right half of each eye sends its messages to the left hemisphere, the left half to the right hemisphere. In this experiment the word “heart” was flashed before the patients, with the “he” to the left of the eye’s fixation point and the “art” to the right. Normally, if any person were asked to report this experience, she would report seeing the word “heart.” The split-brain patients responded differently, depending on which hemisphere was controlling the response.

When asked to point with the left hand to the word seen, the patients pointed to “he,” but when asked to do so with the right hand, they pointed to “art.” The simultaneous experience of each hemisphere was unique and independent of each other in these patients. The verbal hemisphere gave one answer, the nonverbal hemisphere another. We discuss further important implications relating to the nature of these divisions later in this section.

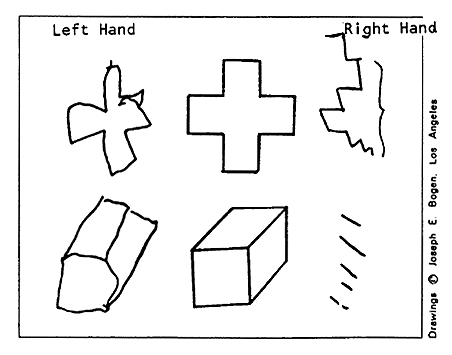

Although drawn by a poor draftsman, from the above image you can see that the left hand, controlled by the right hemisphere, is clearly able to copy the cross and rectangular box in their entirety. All sides are attached and connected. Whereas the right hand, controlled by the left hemisphere, has no ability to see the figure whole, so produces a group of lines that are not the least bit organized, are in no way connected together and don’t make up the whole.

One side of the brain—the right hemisphere in most people—is highly involved in producing and maintaining this overall comprehensive outlook. This makes the right hemisphere better, for example, at avoiding fake news. One innovative research study used electrical stimulation to temporarily inactivate either the left or right hemisphere. With one side of the brain or another knocked out, the researchers presented a fake syllogism to the subjects. For example:

“All hippopotamuses have 4 legs.

All dogs have 4 legs.

Therefore, all dogs are hippopotamuses.”

With the brain’s right hemisphere inactivated, causing the person to operate in what the researchers called the “left self” mode (with the left hemisphere in control), the solutions were limited to the internal consistency of the syllogism rather than its correspondence to external reality. In our example above, the subject would insist that all dogs are hippopotamuses “because it says so.”

By contrast, when the left hemisphere was inactivated, the same person, but now operating in the “right self” mode, would reject a similar syllogism as wrong because “everyone knows that dogs are not hippopotamuses.” There is a sense of an overall perspective and context that’s activated in one side of the brain, and something closer to a localized, step-by-step analysis of the text alone is activated in the other.

Both the structure and function of these two half brains underlie the two modes of consciousness that coexist within each one of us: normal consciousness and a latent more advanced cognitive capacity whose development is part of everyone’s natural endowment. We will discuss this next.