Reclaiming the Public Square

To help bring about a healthy information ecosystem online, and thus a healthy society free of mass manipulation, we need to not just learn about our human nature but also make effective regulatory reforms.

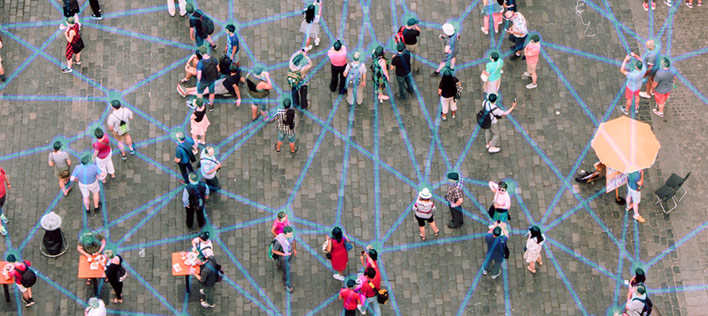

We have now arrived at a unique historical place where human nature, influenced by events and trends, meets powerful information systems with the capacity to massively amplify or distort our perceptions. Global communication is now instantaneous, hyper-social, and intensely networked. It easily crosses borders and has surpassed the traditional mechanisms for maintaining the integrity of information and debate.

While tech companies do have a responsibility to counteract the most damaging forms of disinformation, we cannot depend on them alone to act as the arbiters of truth. Managing the information ecosystem has to be a matter of public policy.

Democracy and human rights depend on a healthy information ecosystem. Hundreds of years ago the challenges brought on by the printing press were met with diplomatic and public policy by the European states. The Protestant and Catholic organizations massively increased and standardized the public’s education so as to rebuild the sensemaking apparatus and enable it to handle the greater variety and flow of information.

In this new disrupted time, we have attempted to protect ourselves by pointing fingers at tech companies and pressuring them to address the damage that occurs on their platforms. While tech companies do have a responsibility to counteract the most damaging forms of disinformation, we cannot depend on them alone to act as the arbiters of truth. Managing the information ecosystem has to be a matter of public policy. Systems of such global reach and importance cannot be governed solely by individual companies. The policy has to reach beyond the applications themselves. Disinformation and misinformation are fueled by a lack of trust. While the global decline in trust has been decades in the making there are practical steps that can reverse this trend. The non-profit organization, Maplight, usefully identifies six core principles that can shape public policy: transparency, accountability, standards, coordination, adaptability and inclusivity.

Transparency

Transparency is supported by making it easy for researchers and journalists to study the algorithms and information flow on the social media platforms. In his book, The Hype Machine, Sinan Aral points out the importance of this when it comes to protecting elections from foreign and domestic interference. He states that the Russian attack on the 2016 US election spread misinformation to at least 126 million people on Facebook and 20 million on Instagram and posted 10 million tweets from accounts with more than 6 million followers on twitter. We know that 44 percent of the voting age Americans visited a fake news source in the final weeks before the election. What we don’t know is whether this tipped the 2016 election.

In order to understand the impact of disinformation on elections, the independent researchers and the social media companies must work in collaboration. This is where the much-needed privacy regulation has to be implemented in a way that does not block these assessments. When data is released to researchers it is anonymized so that identifying information is removed. Aral was impressed by the commitment of Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey to supporting research into the spread of false news on twitter (which we summarized above). Very recently Facebook released an immense dataset to Social Science One at Harvard. This dataset included the website URLs posted on Facebook that were either viewed, shared, liked, reacted to, shared without viewing, or otherwise responded to.

It will require the action of legislators to mount enough pressure to ensure that the social media firms continue to provide accurate and representative data so that data and social scientists can understand how social media is affecting us.

Accountability

The technology companies and political actors who use the platforms have extensive and precise knowledge of individuals, but the people don’t know who is trying to influence them. Dark money is a practice in which non-profits can spend on political campaigns without revealing who their donor base is. In addition to using the targeting technology of social media, the dark money groups set up fake foundations purporting to be for general policy, scientific, or education purposes. They create websites masquerading as local news or other forms of journalism. A lot of this can be corrected by improving and enforcing laws on campaign finance disclosure. For social media giants it means clearly marking the political ads, memes, and stories that flow across their platforms. This is similar to the legislated labelling of packaged food that warns consumers about its content and quality. Also, it means applying the same constraints, prior to elections, that apply to broadcast media. Twitter, for example, disallows any paid political advertising prior to elections.

Standards

The remedies that the major tech companies are applying to stem the flow of misinformation are badly needed but they are piecemeal and reactive. They respond after things go really badly or there is a public outcry. This is easily understood from the perspective that any efforts to protect our information environment are likely to negatively impact revenue for the companies. Content that trends and attracts attention because it incites anger, hatred, and outrage still brings in ad dollars. This kind of thinking will only benefit companies in the short term. Sinan Aral points out that companies that align shareholder value with societal values will be more likely to produce long-term value, whereas designs that produce short term profit at the expense of societal value (negative impact) will lead to public backlash and a likelihood of lawsuits, punitive penalties, and aggressive regulatory response—as for example the recent German laws that might wipe-out the Facebook ad business in that country.

Philip Napoli, in his book Social Media and the Public Interest, argues for reviving the principle of the public interest. The social media applications are intensely individualistic: they were designed to foster self-expression. The platforms, collectively, enable the search for and dissemination of news and information. “Missing here are any broader, explicitly articulated institutional norms and values that guide these platforms, along the lines of those articulated by the various professional associations operating in the journalism field” (Social Media and the Public Interest, p. 135)

Interoperability

Competition is supposed to be the way to ensure an industry serves its customers. If you wish to move your phone service to another carrier you can keep your existing number. You can still talk to everyone that you previous could. We should note that this “number portability” had to be enforced through legislation before the telecom giants made it possible. Making number portability possible required massive changes by the telecom giants and was not in their interests, since it allowed customers switch to competitors offering cheaper or better service. But it was seen by society as important enough to demand it through legislation. An upstart social media app can’t compete on price, since they are all free, but it could compete with features like no surveillance, or enforced civil norms, or no political ads. But in order to switch to it you would have to convince your friends to join as well. They in turn would have to convince theirs to do so. This is why there haven’t been viable competitors. But suppose you could move your identity to the new platform and yet maintain your current network.

There are many challenges to this scheme. Each social media app has its own message format. Twitter messages are public and limited to 240 characters; WhatsApp messages are private and unlimited in length. Snapchat messages disappear; Facebook messages persist indefinitely. But as Sinan Aral points out in The Hype Machine, these companies have solved even greater technical challenges to get where they are today.

Coordination

Deceptive digital operations work across multiple platforms. They may use a combination of fake news sites (astroturfing), Facebook groups, YouTube videos, and Twitter accounts. Instead of the more easily detected bots, they rely on social media “influencers” to spread their messages, discredit critics and silence dissent. The technology platforms need to share information and align their policies to counter multi-platform attacks. Since disinformation campaigns cross borders easily governments will also need to share information and to ensure that policy is aligned internationally.

We need a similar level of coordination across our news organizations. The traditional media of magazines, newspapers, and television remains the primary source of news content and is an important part of our information ecosystem. We know there is still some trust remaining in mainstream news because foreign and hyperpartisan disinformation campaigns design their fake news sites and journals to resemble the real ones. The legitimate newsrooms face two big challenges. They have to get newsworthy stories out quickly or they will be scooped by others, but responsible fact checking slows that down. The juiciest (most revenue producing) stories have the highest probability of being false or misleading. The other challenge they face is polarization, which means that a large part of the population will not trust any outlet they consider biased against their political side.

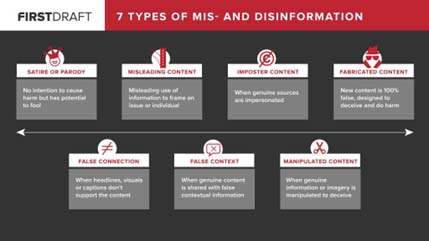

To address this problem Claire Wardle, the founder of First Draft News (a project “to fight mis- and disinformation online” from 2015-2022), devised the idea of Cross Check, in which all the major news outlets in a country collaborate on confirming or debunking new stories. A right-wing reader may not trust a left-wing newspaper but will trust a right-wing newspaper. Conversely, a left-wing reader is willing to trust a left-wing newspaper if it debunks a story. Essentially the news media are pooling their trust capital, allowing them to present a unified consensus of the stories, acceptable to both sides. Cross Check has been successfully piloted in Europe and Australia.

Adaptability

Regulations and policies need to be crafted so that they are not tied to a particular technology. Technology advances constantly and so regulations become irrelevant if they are not assessed and adapted regularly. This is by no means an easy task. The Maplight group recommends legislation that mandates a standard but leaves the technical implementation up to the companies. Disinformation is primarily spread by inauthentic accounts and websites. The legislation might mandate that social apps must identify, and remedy, coordinated inauthentic behaviour. How it does this and how it even defines inauthentic behaviour will evolve over time. Maplight recommends setting up an agency or taskforce to monitor the latest developments in deceptive digital technology, so that governments are not constantly being caught off guard. The regulatory requirements also need to be adjusted according to the size of the application. A small start-up should not face the same regulatory demands as a Facebook or Google.

Inclusiveness

The institutional and structural inequality that is present in the world is reflected and perpetuated on social media.

Algorithms are often assumed to be neutral or factual. But they are designed by humans and so they are vulnerable to our same biases. This is especially the case with machine learning algorithms. A machine learning algorithm is trained by feeding it large amount of data. The selection of which data to start with can introduce racial and other biases into the machine’s learning. In her TED Talk, the mathematician Cathy O’Neil characterizes algorithms as opinions embedded in code. The institutional and structural inequality that is present in the world is reflected and perpetuated on social media. Racial minorities are often the target of digital campaigns. During the 2016 and 2018 US elections the Russian propaganda deliberately infiltrated the online communities of black and Latinx activists in order to inflame political tensions around issues of racial justice and to suppress the vote in those communities. (Report from the United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence.)

Global Citizens

Social media plays very much on our instinctive needs and desires for attention and tribalism; thus, it is even more necessary to build self-awareness and to understand the vulnerabilities of our perceptual systems.

We are at a unique point in history where it is possible to speak on global platforms without having to pass through media gatekeepers or first become a talking head or journalist. Local newspapers had their letters to the editor, but this offered nothing approaching the level of discourse that is now possible. We might need some training on how to behave in a massively networked and collaborative world. Developing behavioral norms is an ancient technique that our species evolved to manage complex social interaction.

Reddit and Wikipedia have had great success in improving discourse by making their norms explicit. Reddit posts a set of guidelines (Reddiquette) that are designed to reduce trolling, harassment, flame wars, and manipulated content. First and foremost, it reminds us to remember the human—to remember that we are speaking to other human beings beyond our screen and to consider how we would act were we face-to-face with that person. The administrators enforce etiquette beginning with asking you, nicely, to knock it off, then less nicely. If that doesn’t work, they begin removing content and restricting privileges. As a last resort they will ban obnoxious users from the communities. Both Wikipedia and Reddit provide a way for contributors to build a trust score. In Wikipedia a greater trust score can give more weight to a person’s edits.

The Psychologist Gordon Pennycook and colleagues were able to induce people to think about accuracy simply by sending Twitter users a single message asking their opinions about the accuracy of a single headline.

Social media plays very much on our instinctive needs and desires for attention and tribalism; thus, it is even more necessary to build self-awareness and to understand the vulnerabilities of our perceptual systems. For example, we seem to use different thinking modes when we evaluate a story for truth or plausibility versus when we decide to share something. It is not that we are unable to discern the true from the false, but we are provoked into sharing false or inflammatory stories by our desire to attract attention, signal our group membership, or engage in morally evocative content. The remedy to this may be easier than we think. The Psychologist Gordon Pennycook and colleagues were able to induce people to think about accuracy simply by sending Twitter users a single message asking their opinions about the accuracy of a single headline. They found this decreased the number of false stories shared by these users, but not the number of true ones

The Public Square

You cannot have collective action where you have rampant distrust.

In his book, The Square and the Tower, Niall Ferguson takes us to the Piazza del Campo in Siena, Italy. This square is considered to be the embodiment of the medieval city. The plaza was built to allow the merchants and the citizens to intermingle, to buy and sell goods and services and to trade in gossip. Overshadowing the square is the Torre del Mangia, the Tower. The tower is built onto the Palazzo Pubblico, the town hall, which is part of the square. The tower symbolizes and projects the secular authority that regulates the city. Niall Ferguson chose this image of the tower and the square for his book because it clearly illustrates the tension that has existed between hierarchies and networks throughout history. Commercial and trade networks seek as much freedom as possible: laws and regulations tend to limit profits and hamper innovation. But where there is an absence of central authority or where it is weak and ineffectual, you do not have infinite profits and innovation, instead you have gangsters, price-fixing, and exploitation.

In multiple countries we see a loss of trust in institutions, including those of government, news media, education, and science. This loss of trust represents one our greatest challenges as a species, because to address problems like climate change, mass migration, and poverty requires collective action. You cannot have collective action where you have rampant distrust. Principles like transparency, accountability, and standards can foster trust that not only is the information ecosystem being governed, it is being governed in a way that is open and accountable to the citizens.

The European Union’s recently approved Digital Markets Act and Digital Services Act mark an initial step toward a healthy 21st Century information ecosystem by requiring transparency, accountability, standards, and other promising means of combatting disinformation, misinformation, and distrust.

The Anxious Generation

How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness

An essential investigation into the collapse of youth mental health—and a plan for a healthier, freer childhood.

By Jonathan Haidt (2024)

In the series: Social Networks

Related articles:

Further Reading »

Websites:

Data & Society

Data & Society studies the social implications of data-centric technologies & automation. It has a wealth of information and articles on social media and other important topics of the digital age.

Stanford Internet Observatory

The Stanford Internet Observatory is a cross-disciplinary program of research, teaching and policy engagement for the study of abuse in current information technologies, with a focus on social media.

Profiles:

Sinan Aral

Sinan Aral is the David Austin Professor of Management, IT, Marketing and Data Science at MIT, Director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy (IDE) and a founding partner at Manifest Capital. He has done extensive research on the social and economic impacts of the digital economy, artificial intelligence, machine learning, natural language processing, social technologies like digital social networks.

Renée DirResta

Renée DiResta is the technical research manager at Stanford Internet Observatory, a cross-disciplinary program of research, teaching and policy engagement for the study of abuse in current information technologies. Renee investigates the spread of malign narratives across social networks and assists policymakers in devising responses to the problem. Renee has studied influence operations and computational propaganda in the context of pseudoscience conspiracies, terrorist activity, and state-sponsored information warfare, and has advised Congress, the State Department, and other academic, civil society, and business organizations on the topic. At the behest of SSCI, she led one of the two research teams that produced comprehensive assessments of the Internet Research Agency’s and GRU’s influence operations targeting the U.S. from 2014-2018.

YouTube talks:

The Internet’s Original Sin

Renee DiResta walks shows how the business models of the internet companies led to platforms that were designed for propaganda

Articles:

Computational Propaganda

“Computational Propaganda: If You Make It Trend, You Make It True”

The Yale Review

Claire Wardle

Dr. Claire Wardle is the co-founder and leader of First Draft, the world’s foremost non-profit focused on research and practice to address mis- and disinformation.

Zeynep Tufekci

Zeynep is an associate professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill at the School of Information and Library Science, a contributing opinion writer at the New York Times, and a faculty associate at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University. Her first book, Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest provided a firsthand account of modern protest fueled by social movements on the internet.

She writes regularly for the The New York Times and The New Yorker

TED Talk:

WATCH: We’re building a dystopia just to make people click on ads

External Stories and Videos

Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid

Jonathan Haidt, The Atlantic

Social media has created a unique environment for the intensification and exploitation of our tribal instincts. How are we to understand the fragmentation and bitter divisions we are currently experiencing, not only in the US, but throughout the world? What steps can we take to reform our institutions and social media and, more importantly, to stabilize and repair democratic society?

Watch: Renée DiResta: How to Beat Bad Information

Stanford University School of Engineering

Renée DiResta is research manager at the Stanford Internet Observatory, a multi-disciplinary center that focuses on abuses of information technology, particularly social media. She’s an expert in the role technology platforms and their “curatorial” algorithms play in the rise and spread of misinformation and disinformation.