The Evolution of Online Social Networking

To understand what is happening right now we need understand how the world wide web has changed from when it was first invented by Tim Berners-Lee in 1989. The web we see now is often called web 2.0 to mark this evolution. This transition was made possible by the pervasive use of computer algorithms. Prior to the advent of these algorithms, we explored the web like some new land. Now, in a very real way the web has begun to explore us.

The web burgeoned in the 1990s since it cost almost nothing to publish content with the already existing tools for word processing, image editing, and digital video. During this period, often called web 1.0, users had to actively search for content. There were plenty of options for active discussion and participation, especially for the web-savvy. But if you wanted to be self-supporting as a blogger or seller, it was very hard to build a large audience. Very few were lucky enough to attract many people to their site when it was just one of millions of others out there. The difficulty of attracting visitors was one of the factors leading to the dot-com bust in the late 1990s. Start-ups burned through their investment capital by spending it on newspaper, television, and radio ads, in order to drive people to their sites, so that they could make money through presenting even more ads.

YouTube solved this problem by making it easier for video makers and viewers to find each other. They did this by applying different classes of algorithms to increase the likelihood that visitors to YouTube would find videos that would interest them. This engagement model kept people on the site so that more ads could be presented to them. These algorithms also changed the flow of information. Web 1.0 was becoming Web 2.0. We no longer had to go out and search for content. Content was searching for us and arriving in front of us in a way that felt more like the familiar passive media consumption of the past but tailored to our personal interests.

Us

In his Wired article, Steven Levy draws from a 17-page chunk from the (mostly destroyed) journals of Mark Zuckerberg to examine a key point in the evolution of Facebook. One of the preoccupations within this journal was a product that he called Feed (later named News Feed). This signalled a dramatic change to the Facebook concept, which would later have real-life impacts on global events in war and in politics. At the beginning, Facebook required more active effort on the part of users to connect with friends. You had to go to your friends’ profiles in order to see what they were up to and post your updates on their “walls”. This was very much in line with the active participation that defined the web 1.0 world. News Feed changed all that.

Now your friends’ updates were pushed to you without any effort on your part. The news feed would make it easy for people to see what was important among the friends with whom they were connected. Steven Levy notes that Zuckerberg used the word “interesting-ness” to cover the kinds of stories that should appear in a news feed. They needed to be “centered around your social circle.” There was to be an emphasis on changes in personal relationships and life events. The new feed was to favour these over interesting events or other information outside your social circle.

When News Feed launched in 2006 it appeared to be disastrous; it had major privacy flaws and people protested heavily against it. But once Facebook employees looked at the data, it was clear that people were spending more time on Facebook because of it. The product itself had helped the protests against it go viral. Facebook fixed the more serious privacy issues, the protests died down, and Facebook continued to grow exponentially.

The Advertising Model

The social media apps emphasized personal expression and personal connection. They developed classification and association algorithms to find friends and people for users to connect to. The rougher and less polished the content that you posted the more authentic you appeared to friends and followers. The social media apps’ recommendation engines brought the videos, memes, stories, and comments that would most appeal to you. The highly social nature of these apps and their ease of use attracted millions of users, and from these millions of users flowed massive amounts of content. Algorithms were needed to manage this content.

Facebook has a record of your “social network graph” which models the interactions between you and others to determine how important you are, how many connections you have made with others, and so on. It answers questions such as Who do you know? What is your social milieu? Is it primarily middle class or poor, urban or rural? Are you conservative or liberal? What do you believe in? All of this information is gathered through what you post, share, and like. Advertisers uses this data to target ads to likely buyers. This data is fed into filtering and prioritization algorithms so that they surface the stories from your friend and follower networks that are mostly likely to keep you liking and sharing. The longer you stay glued to your phone the more ads you will encounter.

In the series: Taming the Web

Further Reading »

Websites:

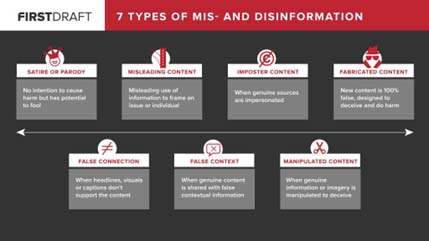

First Draft

The mission of First Draft is to protect communities from harmful misinformation. Through their Cross Check program, they work with a global network of journalists to investigate and verify emerging news stories. The site has many research articles, education, and guidelines on misinformation and infodemics.

Data & Society

Data & Society studies the social implications of data-centric technologies & automation. It has a wealth of information and articles on social media and other important topics of the digital age.

Stanford Internet Observatory

The Stanford Internet Observatory is a cross-disciplinary program of research, teaching and policy engagement for the study of abuse in current information technologies, with a focus on social media.

Profiles:

Sinan Aral

Sinan Aral is the David Austin Professor of Management, IT, Marketing and Data Science at MIT, Director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy (IDE) and a founding partner at Manifest Capital. He has done extensive research on the social and economic impacts of the digital economy, artificial intelligence, machine learning, natural language processing, social technologies like digital social networks.

Renée DiResta

Renée DiResta is the technical research manager at Stanford Internet Observatory, a cross-disciplinary program of research, teaching and policy engagement for the study of abuse in current information technologies. Renee investigates the spread of malign narratives across social networks and assists policymakers in devising responses to the problem. Renee has studied influence operations and computational propaganda in the context of pseudoscience conspiracies, terrorist activity, and state-sponsored information warfare, and has advised Congress, the State Department, and other academic, civil society, and business organizations on the topic. At the behest of SSCI, she led one of the two research teams that produced comprehensive assessments of the Internet Research Agency’s and GRU’s influence operations targeting the U.S. from 2014-2018.

YouTube talks:

The Internet’s Original Sin

Renee DiResta walks shows how the business models of the internet companies led to platforms that were designed for propaganda

Articles:

Computational Propaganda

“Computational Propaganda: If You Make It Trend, You Make It True”

The Yale Review

Claire Wardle

Dr. Claire Wardle is the co-founder and leader of First Draft, the world’s foremost non-profit focused on research and practice to address mis- and disinformation.

Zeynep Tufekci

Zeynep is an associate professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill at the School of Information and Library Science, a contributing opinion writer at the New York Times, and a faculty associate at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University. Her first book, Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest provided a firsthand account of modern protest fueled by social movements on the internet.

She writes regularly for the The New York Times and The New Yorker

TED Talk: