Biological Traits and the Fiction of Race

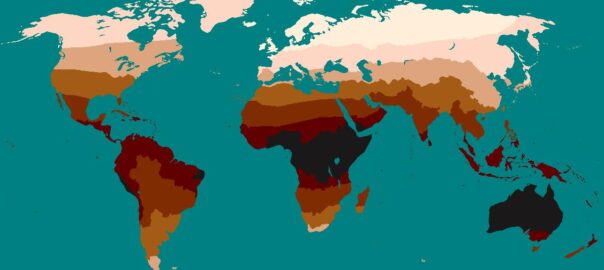

Global distribution of skin color. Credit: UPV/EHU [Science20.com]

Ancient DNA has enabled scientists to understand how complex biological traits evolve over time. They can follow the complex evolution of skin pigmentation and traits such as blue eyes and height.

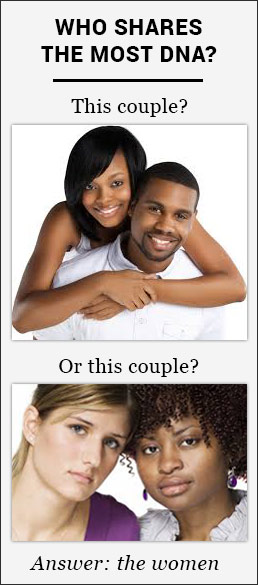

Skin color is extremely variable, even on the African continent, and is still evolving. A study of diverse African groups led by University of Pennsylvania geneticists shows that “most of the genetic variants associated with light and dark pigmentation appear to have originated more than 300,000 years ago in Africa, and some emerged roughly one million years ago, well before the emergence of modern humans. The older version of these variants in many cases was the one associated with lighter skin, suggesting that perhaps the ancestral state of humans was moderately pigmented rather than darkly pigmented skin.”

Recall that the chimpanzee is our nearest extant animal relative and 98.7% genetically identical to us. “If you were to shave a chimp, it has light pigmentation,” says Sarah Tishkoff, the senior author of the study, “so it makes sense that skin color in the ancestors of modern humans could have been relatively light.” Tishkoff noted that this work underscores the diversity of African populations and the lack of support for biological notions of race.

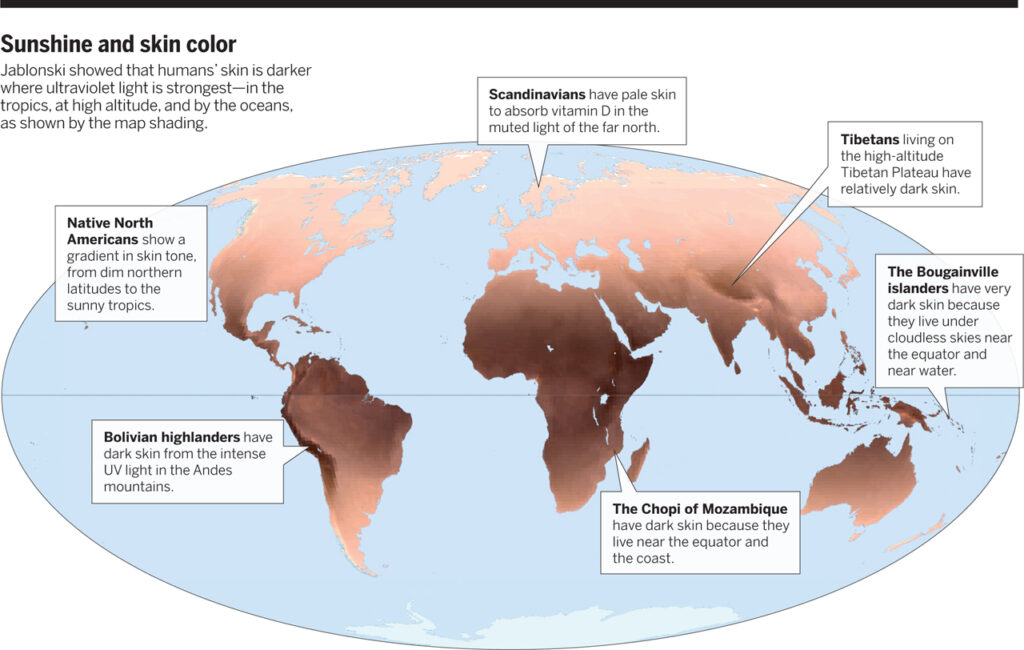

To survive entirely as a bipedal animal, our bodies had to adapt to the climate and conditions in which we found ourselves. The shapes of our noses and lips changed to accommodate changes in temperature and humidity. Thin noses protect the body from breathing in too much bitterly cold air down into the lungs; wide noses and thicker lips have the opposite function. Afro-textured hair increased circulation of cool air onto the scalp while we lived on the open savannah. Losing body hair enabled us to sweat and so cool down more easily. In lush rainforests, where UV-B radiation was not in excess, light pigmentation would not have been nearly as detrimental. But as we moved from forests to the open savannah, we needed darker skin to protect us from the sun’s ultraviolet radiation.

So we produced more melanin—a term used to describe a large group of related molecules responsible for many biological functions, including pigmentation of skin and hair and photoprotection of skin and eye. It protected us against skin cancer and the depletion of folate—a type of B vitamin—vital to reproduction.

Natural selection favored two genetic solutions for people living far from the equator who may not get enough UV to synthesize vitamin D, essential for healthy bones. As we moved away from the equator we evolved paler skin, able to absorb UV more efficiently, and lactose tolerance to digest the sugars and vitamin D naturally found in milk.

DNA sequencing in 2018 led to the discovery that the 10,000-year-old “Cheddar Man,” Britain’s oldest complete skeleton, had dark-brown skin. Now, a new study may offer additional insight into our assumptions about the skin color of our European ancestors. Led by Guido Barbujani at the University of Ferrara in Italy, researchers found that for most of Europe’s history, the majority of its inhabitants had dark skin. Only around 3,000 years ago did lighter skin tones become dominant.

In this lecture, Leakey Foundation grantee Nina Jablonski discusses the evolution of human skin color and how color-based race concepts have influenced societies and impacted social well-being.

Skin color is a plastic trait that has changed a number of times in varying populations throughout our history. There’s no such thing as an African race or a white race; and no inherent value in classifying people by skin color, since you can find the same color evolving in many lineages of people.

She Has Her Mother’s Laugh

The Powers, Perversions and Potential of Heredity

Carl Zimmer

Our understanding of heredity has come a long way and holds much promise, but we’ll need wise judgement to manage the emerging science of genetic engineering.

In the series: Genetics and Human Evolution

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

Basic Information about Genomics

Quick lessons to help you learn more about genomics, so you can explore your own data in a more meaningful way.

Culture Change: War Bands Hooked Up with Neolithic Farm Women

Researchers find that the appearance in Europe of pottery imprinted with cord-like designs may have been the result of intermarriage between Neolithic farm women of Europe and incoming warriors from the Pontic and Caspian steppes near the Black and Caspian seas.

Scientists Find Evidence of ‘Ghost Population’ of Ancient Humans

Ian Sample, The Guardian

Traces of unknown ancestor emerged when researchers analyzed genomes from west African populations.