Stories and Storytelling:

The Science of Storytelling

“Stories are actually a form of technology. They are tools that were designed by our ancestors to alleviate depression, reduce anxiety, kindle creativity, spark courage and meet a variety of other psychological challenges of being human.” ―Angus Fletcher, Wonderworks

Science can tell us much about how we process the language and imagery contained in stories. The brain, for instance, it seems, does not make much of a distinction between experiencing something and reading or listening to something. When you read a word such as “lavender,” “cinnamon” or “soap,” not only the language-processing areas of your brain are activated, but also those devoted to dealing with smells. In his fascinating book Louder Than Words, psychologist Benjamin Bergen makes a convincing case that in many situations, “we understand language by simulating in our minds what it would be like to experience the things that the language describes.” Studies that compare fMRI imaging during visual, motor, and linguistic tasks reveal similar brain activity when we perceive objects as when we imagine them; similar results are found when we mentally visualize a motor activity, such as shooting a basketball, and when we hear a description about that activity.

A study published in February 2012 at Emory University found that a region of the brain important for sensing texture through touch, called the parietal operculum, is also activated when someone listens to a sentence with a description of texture, but only if a metaphor is used. As science writer Annie Murphy Paul wrote in her essay Your Brain on Fiction, “while metaphors like ‘The singer had a velvet voice’ and ‘He had leathery hands’ roused the sensory cortex, phrases matched for meaning, like ‘The singer had a pleasing voice’ and ‘He had strong hands’ did not.”

According to Will Storr, “Analysis of language revealed the extraordinary fact that we use around one metaphor, every ten seconds of speech or written word.” In his book The Science of Storytelling, he points out that “Neuroscientists are building a powerful case that metaphor is far more important to human cognition than has ever been imagined. Many argue it’s the fundamental way that brains understand abstract concepts, such as love, joy, society and economy. It’s simply not possible to comprehend these ideas in any useful sense, then, without attaching them to concepts that have physical properties: things that bloom and warm and stretch and shrink.”

We all experience the effects that stories can have on us: some scare, some inspire, some move us to nostalgia or sorrow, stir empathy, motivate us to action, and so on. Angus Fletcher, who is both a neuroscientist and professor of literature, suggests that stories have always had such purposes. He describes a story as “a narrative-emotional technology that helped our ancestors cope with the psychological challenges posed by human biology.”

We’ve been a social species, whose survival has depended upon human cooperation for hundreds of thousands of years. But the acceleration of socialization over the last 1,000 years, according to developmental psychologist Professor Bruce Hood, has left us with brains that are “exquisitely engineered to interact with other brains.”

Studies have shown that stories offer a unique opportunity to engage in “theory of mind”—our ability to understand and empathize with another’s mental state. Fletcher’s own experimental work includes a 2016 study into the psychological effects of “free indirect discourse,” a form of narrative that draws attention away from the narrator, instead slipping in and out of characters’ experiences and consciousness. The study found that readers of the latter tales not only offered more empathic responses to a follow-up questionnaire, they also showed a greater understanding of behaviors and moral choices they didn’t identify with. As Fletcher says: “Our brains grow by being able to enter into other minds and imagine ourselves as other people. …literature gives you direct access, it literally allows you to leap into the mind of Jane Austen or Homer or Maya Angelou etc., and just go.”

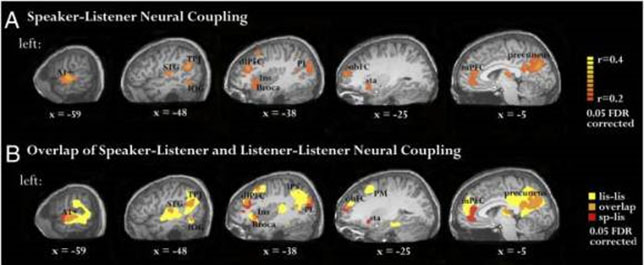

One of the most interesting details, shared in the graphic above, comes from a Princeton University Study, which demonstrated that the brain of a person telling a story and the brain of a person listening to it can synchronize. The link that is possible between a storyteller and their audience, what the paper describes as “speaker–listener neural coupling,” can be clearly seen in this image. The authors found that the greater the anticipatory speaker-listener coupling, the greater the understanding.

In his intriguing book Wonderworks, Fletcher identifies 25 narrative “tools” or “inventions” that trigger traceable, evidenced neurological outcomes in the reader/listener/viewer. He points out that although the science is in its infancy, early findings reveal that “combined with the established areas of psychological and psychiatric research, they produce an intricate picture of how literature’s inventions can plug into different regions of our brain—the emotion centres of our amygdala, the imagination hubs of our default mode network, the spiritual nodes of our parietal lobe, the heart softeners of our empathy system, the Gods-Eye elevators of our prefrontal neurons, the pleasure injectors of our caudate nucleus, the psychedelic pathways of our visual cortex—to alleviate depression, reduce anxiety, sharpen intelligence, increase mental energy, kindle creativity, inspire confidence, and enrich our days with myriad other psychological benefits.”

We’re selecting here one invention, the results of which reflect the findings that Ornstein presents in God 4.0—On the Nature of Higher Consciousness and the Experience Called “God.” Fletcher calls this “the stretch” and describes it as follows:

The taking of a regular pattern of plot or character or story world or narrative style or any other core component of story—and extending the pattern further. … The stretch is the invention at the root of all literary wonder: the marvel that comes from stretching regular objects into metaphors, the dazzle that comes from stretching regular rhythms of speech into poetic meters, and the awe that comes from stretching regular humans into heroes.

And the stretch is also the invention at the root of the plot twist. The plot twist takes a story chain and stretches it one link further….

The stretch is a simple device, but its effects on our brain can be profound. It’s been linked in modern psychology labs to a shift of neural attention that flings our focus outward, decreasing activity in our parietal lobe—a brain region associated with mental representations of self. The result is that we quite literally feel the borders of our self dissolving, even to the point of “self-annihilation” …or what the early 20th-century–founder of modern psychology, William James, described more vividly as a spiritual experience.

These experiences are the mystic mental states that sages from days immemorial have preached as the highest good of human life. And in the case of literature, at least, the good really exists. The stretch has been connected by modern neuroscientists to significant increases in both our generosity and our sense of personal well-being. Which is to say: fictional plot twists, metaphors, and heroic characters dispense a pair of factual benefits. By immersing our neural circuitry in the feelings of things bigger, they elevate our charity and our happiness, spiriting us closer to a scientific Shangri-la.

We saw this when we looked briefly at Homer; we noted a similar experience evoked in audiences attending the theater in ancient Greece. And it is a key to foundational literature—where the wisest of storytellers, through imagery and the richness of their languages and through the multileveled structure of their stories, provide a beacon for those open to a new understanding of humanity’s evolutionary process and who might hope to see themselves as part of that transformation.

Back in 1972 in The Psychology of Consciousness, Robert Ornstein described pioneering studies of brain activation using an electroencephalograph (EEG). One study compared subjects’ brain activity while reading two types of written material: technical passages and folk tales. There was no change in the level of activity in the left hemisphere, but the right hemisphere was more activated while the subject was reading the stories than while reading the technical material. This finding was explained by considering the nature of the material.

Technical material is almost exclusively logical. In stories, on the other hand, many things happen at once; the sense of a story emerges through a combination of style, plot, and evoked images and feelings. “Thus, it appears that language in the form of stories can stimulate activity of the right hemisphere,” said Ornstein and added that “The storyteller himself is one of the most important elements in traditions, in using language to make an end run around the verbal intellect, to affect a mode of consciousness not reached by the normal verbal intellectual apparatus.”

The idea and implication that certain stories were designed to develop a higher perceptive capacity in us is a concept introduced to the Western reader by Idries Shah in the late 1960s. Ornstein, familiar with Shah’s work, recognized that the activation of the right hemisphere as found in EEG studies revealed neurobiological evidence of this. He pointed out at the time that “because we now lack a psychological framework for these nonlinear time experiences means not that they should be ignored entirely; but we must develop a new framework if we are to incorporate them into contemporary science.”

Over the past two decades, neuroscientists have begun using additional devices to look inside our heads, as we experience all sort of things. By connecting their latest research with archeology, religious history and psychology, Ornstein was able to complete our understanding of this framework, which he describes in his final work, God 4.0, published posthumously in 2021. He describes the circumstances and what actually happens neurobiologically when our brains are activated each time we understand a problem or understand it anew. Along with other processes, this instinctive brain reaction forms the foundation of the insight behind the “higher” perceptions referred to by Shah. It can be understood as a continuum from breaking through the mental barriers that constrain small daily insights, to breakthroughs in artistic and scientific creativity, and onwards to a transcendent understanding, the activation of a “second network of cognition.”

There is an irreplaceable corpus of teaching stories and narratives whose purpose is the precise development of this latent faculty—and it is latent in all of us. The material was selected by Idries Shah specifically for these times. It stands uniquely beyond entertainment—although its stories are entertaining—and beyond therapy—it operates when the person is balanced, straightforward and sincere. It has been described as an advanced psychology (i.e., an advanced study of the mind or soul) since it offers a comprehensive curriculum through which this cognitive capacity becomes one’s own, running in parallel to our normal state of consciousness.

An alternative perspective on life develops, along with a more comprehensive understanding which results in actions being motivated more by an intuitive capacity than by the self-centered approach to action through normal conscious behavior.

In a world that seems overwhelmed by binary attitudes that at times appear to threaten our very existence, the development of this latent capacity seems worthy of our attention and time.

A story goes that in the 11th century, a great Sufi, Abdul Qadir of Gilan, was asked:

Can you not give us power to improve the earth and the light of the people of the earth? We are told that his brow darkened, and he said, “I will do better: I will give this power to your descendants, because as yet there is no hope of such improvement being made on a large enough scale. The devices do not yet exist. You shall be rewarded, and they shall have the reward of their efforts and of your aspiration.”

As Ornstein points out in God 4.0: “We now have an idea of how the process happens in the brain and, importantly, how to develop this innate potential in today’s world.”

Examples of these tales and narratives and more on their instrumental nature can be read in the two pieces that follow: A Unique Form of Literature by Robert Ornstein and, of course, the piece that we also include here entitled “The Teaching Story: Observations of the Folklore of our Modern Thought” written by Idries Shah.

For those interested, the works of Idries Shah referred to here are available from Amazon or through The Idries Shah Foundation. For works by Robert Ornstein please visit Amazon or robertornstein.com.