Stories and Storytelling:

The Written Word

When the Heavens above did not exist

And earth beneath had not come into being—

There was Apsû, the first in ordear, their begetter,

And demiurge Tia-mat, who gave birth to them all;

They had mingled their waters together

Before meadow-land had coalesced and reed-bed was to be found—

When not one of the gods had been formed

Or had come into being, when no destinies had been decreed,

The gods were created within them:

Lah(mu and Lah(amu were formed and came into being….

—Enuma Elish, The Babylonian epic of creation

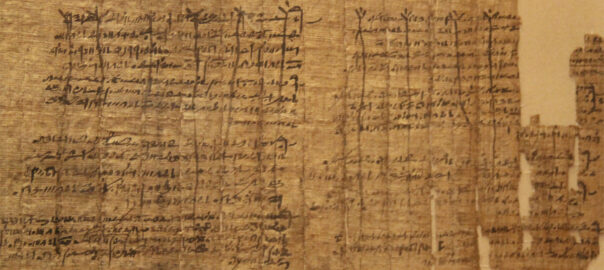

The intersection of oral and written storytelling happened first in Mesopotamia around 5,000 years ago, about 2,500 years before Homer was first written down. Originally, scribes used this new technology only for bookkeeping, recording inventory, or for the equivalent of today’s text messages. But once the first scribes in Ur realized that writing could be used to record their most valued epic stories, their excitement likely matched our own when portable computers came on the scene. They could hardly have predicted the transformations that would occur over time once oral and written technologies merged.

As we show in the Mesopotamia section of this website, once oral stories become written literature, we no longer have to rely on speculation. We read from the clay tablets on which they wrote their myths, poetry and biographies that the people of Babylon believed in a pantheon of gods. From the Enuma Elish, we learn what their relationship was with these gods and how and why this changed over time. From the later Epic of Gilgamesh, we can glimpse their concerns and values, as we join the eponymous hero and delve into themes of heroism, friendship, sexuality, mortality and the search for immortality.

Martin Puchner, professor of English and comparative literature at Harvard University, found, after decades of research, that whenever societies develop writing, oral storytelling initially intersects with writing technologies to produce foundational texts. This happened in Mesopotamia, in Egypt, in India and China, and in the more recent Olmec and Mayan cultures. These are the stories that identify a culture; tell of its members’ origin, their place in the world and their destiny. The Mesopotamians had the Enuma Elish, the Egyptians the Pyramid Texts, the Indians the Vedas; Jews the Torah, Christians the New Testament and the Mayans the Popol Vuh.

Major religions cycle and recycle the same scenarios as do the rest of the world’s storytellers. As we noted already on this site, while Jewish scholars, poets, and intellectuals were exiled in Babylon, bereft of king and temple, they began to collect and create from oral and written sources what we know today as the Old Testament. The oral traditions surrounding them included myths, memories and ideas from Persia, where Zoroastrianism flourished; from Greece; and from Mesopotamia, where the epic tales we mentioned, the Enuma Elish and the Epic of Gilgamesh, were in circulation.

Some of these tales would have been circulating orally and for at least 1,500 years prior to the time they were set down on papyrus by these Jewish scribes. Stories included the Story of the Flood, the stories of the Tower of Babel and of Sodom and Gomorrah; they included the story of Moses, the unifier of the Jews whose infancy bears a remarkable resemblance to that of the Akkadian king Sargon who unified Sumer. Both were found in a reed basket, and both were brought up by royal strangers.

Many of these traditions and cultures share stories based on a world long gone—a world in which people had very different lifestyles and presuppositions than do we. There were many virgin births in the ancient world. The Babylonian God Tammuz was the only son of the god Ea. His mother was a virgin, by the name of Ishtar. Horus of ancient Egypt had the title of “Savior” and was born of the virgin Isis. Even Plato was said to be born of the union of a virgin and a god.

Presentism, or applying a contemporary meaning to the understanding of the peoples of the ancient world and believing in this misunderstanding, is seriously mistaken. The designation “Son of God” was in wide general use in the world of two millennia ago, the title granted for people of great accomplishment, just as we now use metaphorically the term “star” for someone prominent. We know it is fanciful, since the lead actor in a film is not a real star and is not high above us, millions of light-years away. After Julius Caesar was posthumously made a god in 43 BCE, his son Octavius became another Son of God. The emperor Qianlong of China was the “Son of Heaven.” Still today, Sai Baba, who died in India in 2011, is believed by millions to be the Son of God.

Once written down, epic tales can become a fixed narrative of events that people take literally, even though, for example, the two versions of Genesis or the three different versions of the Synoptic Gospels often contradict each other, and lead to other complications as well. As religious historian Géza Vermes points out in his book Jesus: Nativity–Passion–Resurrection, if Jesus is the long-expected Jewish Messiah, he had to be descended from the House of David through the paternal line—hardly possible if he is literally the Son of God, born of a virgin!

Until Christianity took over the Roman world in the late fourth century, foundational narratives that we might call religious were shared across cultures and time, as were metaphors, honorific titles and accolades. In the early Christian world, we see a similar absorption of stories most familiar to the people to whom the “Good News” (The Gospels) was announced.

The Persian sun-god Mithra had a large following in Rome, particularly among the military. At midnight, the first moment of December 25th, the Mithraic temples would be lit up, with priests in white robes at the altars, and boys burning incense, much as we see in Roman Catholic churches at midnight on Christmas Eve in our own time. Mithra, his worshippers believed, had come from heaven to be born as man in order to redeem men from their sins, and he was born of a virgin on December 25th. Shepherds were the first to learn of his birth, just as shepherds are said (according to “Luke,” alone among the evangelists) to have been the first told of the birth of Jesus. At sunrise, the priests would announce: “The god is born.” Then would come rejoicing, followed by a meal representing the Last Supper which Mithra ate with his disciples before his ascension into heaven.

Of course, there are still sane voices who have an understanding of the truth to be found. The Rev. John Shelby Spong writes of the Gospel of John:

The good news of the gospel, as John understands it, is not that you—a wretched, miserable, fallen sinner—have been rescued from your fate and saved from your deserved punishment by the invasive power of a supernatural, heroic God who came to your aid. Nowhere does John give credibility to the dreadful, guilt-producing and guilt-filled mantra that ‘Jesus died for my sins.’ There is rather an incredible new insight into the meaning of life. We are not fallen; we are simply incomplete.

The foundational literature of a culture can become the holy writ or sacred texts of that community. In the seventh century CE, the Prophet Muhammad noted this when he referred to both Jews and Christians as the “People of the Book,” meaning the people of the Abrahamic tradition who received revelations from God just as he received the revelations that would be included in the Qur’an.

From the traditional point of view, “God’s words” were “spoken” directly to Muhammad, as they had been to the Old Testament prophets before him. Today, through the lens of history, brain science and neuroscience, we can understand this in a different way. As we write in God 4.0: the Nature of Higher Consciousness and the Experience Called ‘God’, “A more modern understanding of his revelations might be that at those times, Muhammad experienced a transcendent state of higher consciousness that enabled him to understand a Reality ‘beyond words.’” “I cannot recite” would then indicate that the experience is impossible to put into words.

As a Messenger of Allah, he would recite as much as he could through allegory and metaphor. Like Jesus, Muhammad saw a way to transform both society and the individual, and, through imagery and the richness of Qur’anic Arabic, he could address both. But, as Karen Armstrong has emphasized, “There was no question of a neutral simplistic reading of the scripture. Every single image, statement, and verse in the Qur’an is called an ayat (‘sign,’ ‘symbol,’ ‘parable’), because we can speak of God only analogically.” Idries Shah points out that the Qur’an is to be experienced on many levels, “each one of which has a meaning in accordance with the capacity for understanding of the reader.”

Unlike factual text or legal documents, which benefit from being inscribed, a story once written down—even one rich in analogy and metaphor that holds within it multiple levels of meaning—can, over time, become believed to be literally true, offer “right” or “wrong” answers, and stipulate ways of thinking or belief as well as modes of behavior, many of which apply only to a particular time, culture and conditions.

One reason for this is that our brains want always to simplify—select what is easily grasped and reject the rest. We desperately seek—and inevitably find—a moral in a story, so we can say “Yes, understood—I got that! The lesson is…” and move on. When this happens, a tale loses its ability to enrich and extend our consciousness. Conversely, when we are familiar with an open-ended story, it can, in a sense, remain with us, providing a different, richer understanding and worldview as we experience life and encounter events of a similar structure. Some stories, particularly those selected by the late Idries Shah, are designed for just this purpose, and are in use by thousands of people today.

To quote Robert Ornstein again from our book God 4.0, “You gotta believe” is a better motto, really, for a sports team than it is for a religious organization. Transcendence of ordinary consciousness is not this kind of belief but a discovery and a development inside our minds of a different kind of knowledge. It is not intellectual or emotional, either, but the development of a conscious insight. “You gotta perceive.”