China:

The Hundred Schools of Thought

During the chaos and confusion of the bloody battles and the social disruption of the Spring and Autumn and the Warring States periods, a new and vital cultural and intellectual movement emerged that to this day profoundly influences the lifestyles and social consciousness of millions of people.

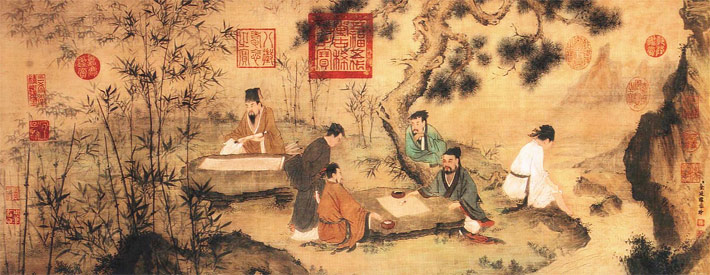

It became known as the Hundred Schools of Thought. It was the Golden Age of Chinese philosophy when thoughts and ideas were discussed and refined by itinerant scholars, often employed by various state rulers as advisers. This period endured until the rise of the Qin dynasty.

These philosophers expressed an entirely new ethic for the region, though each would synthesize and interpret it in his own way. Instead of simply serving one’s own interests or even the interests of friends, family, clan and nation, they suggested that as human beings we should accept responsibility for our own life, actions and thoughts, and that we are capable of a higher morality, the achievement of which is our obligation.

Confucius (550–479 BCE)

Confucius (or Kongzi – Master Kong) represented himself as a transmitter who invented nothing. A hallmark of his teaching was his emphasis on education and study. He wanted his disciples to think for themselves and study the world.

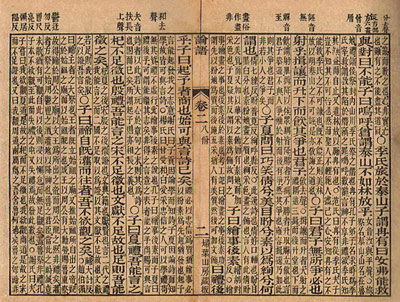

The most reliable information we have of him comes from the Analects (Lunyu), a collection of his sayings, conversations and anecdotes compiled posthumously by his disciples, some of them long after his death.

During his lifetime he was a teacher of history, a public official, and for his final twelve years he wandered the states of China with a few disciples.

Confucius was a traditionalist. In a time of division, chaos, and endless wars between feudal states, he wanted to restore the Mandate of Heaven. He respected authority and believed that a humane society depends on respect for one’s superiors. He was interested in politics not for its ability to wield power but for its ability to work for the good of the realm and the well-being of all citizens. China’s problems could be resolved by a return to the traditions of the legendary Sage Kings of old: if the leader is virtuous, the people will follow his example.

His ideas were not founded on religion or a vision of the divine, but on human potential. Ren, or the essence of being human (“humaneness”), was achieved through self-cultivation and was central to his teaching. It focused on the development of one’s character: moral improvement he saw as part of our very humanity, manifested in the way we express and fulfill our deepest natures.

This involved following a version of the Golden Rule: “By understanding our own wishes, we may image what others desire.”

Junzi originally in pre-Axial times simply meant a gentleman or nobleman. A junzi lived by a code of conduct that defined correct behavior. The junzi or “gentleman,” according to Confucious, was an independent thinker who was not only compassionate but wise, acting to promote the success of others, and more concerned about appreciating others than of others’ failure to appreciate him.

Confucius believed that religious rituals were useful if they enabled individuals to cultivate the qualities of ren, such as reverence, gratitude and humility.

Li originally meant the correct observance of ritual sacrifice and ceremonies performed for the gods, ancestors and other spirits; now li, in Confucius’s view, referred to all occasions of human interaction. In all our dealings with others, we ought to comport ourselves with the same dignity appropriate to a sacred act, banishing acts of violence, rudeness, and maintaining sincerity and social etiquette. Even manners—which could be thought superficial—when practiced with the proper inner disposition had the potential to make us more human.

Li now became a way to transform a person, any person, not just the elite. Confucius channeled what had previously been a kind of magical thinking into something transcendent, available to all of humanity.

His disciples found his path difficult and saw that striving for goodness was a lifelong process that might be unattainable. Unlike the Buddha, Confucius had no goal of liberation or the ending of samsara (reincarnation). His disciples aspired to goodness or ren in this lifetime and for its own sake. Confucius believed that through the cultivation of ren people could achieve social harmony in this life and that this would have a salutary effect throughout society.

Daoism

Daoism was the second most influential philosophy to emerge in China at this time. The Axial concept of Dao is found in all forms of Chinese philosophy, usually translated as the “way” or “path.” Confucians connected the way to culture, the observances of tradition, ritual and li, or personal transformation. To Confucius the Dao meant avoiding excesses, applying conscious self-restraint and self-awareness in word and deed.

The Daoists also understood Dao as the appropriate way for humans to order and live their lives. But for them, following the way was participating in the Dao of nature, the changes and rhythms of the universe, the mystery, intuition, and enigma of the natural world.

Like Confucianism, philosophical Daoism developed as a response to the same political, social and economic pressures, but probably not as a result of one person’s vision and effort. Tradition, however, claims that Daoism was the work of Laozi (or Lao-tsu, “Old Master”) who lived in the fourth century BCE during the Hundred Schools of Thought era. He is traditionally believed to have been a record-keeper at the Zhou Dynasty court.

Daoism was primarily concerned with two classic texts—the Dao de Jing (Tao Te Ching): The Classic of the Way and the Virtue (ca. 300 BCE) and the Zhuangzi. It provided a comprehensive view of the world including the sacred and the ultimate.

The Dao de Jing uses paradox, analogy and ancient sayings to convey its message. It refers to the Dao as the mother of the universe, the source of all existence: the way of nature. The Dao is the named and the nameless; it is primordial, stable, constant, eternal and ineffable, yet it is the source of change and the cycle of life. Human understanding is limited and there are aspects of the Dao that cannot be spoken.

The main focus of the text is to lead human beings back to their natural way of life in harmony with the Dao. According to the Dao de Jing, humans have no special place within the Dao. They are seen as having desires and free will and are instructed to act in accordance with nature and in harmony with the Dao.

A central theme is the concept of nothingness which is used to describe the Dao and three other concepts: virtue (de), natural behavior (ziran), and non-action (wuwei).

De has been translated as virtue, potency, efficiency, integrity or power. The concept of de seems to be a Daoist response to the question of human nature and much of the Dao de Jing concerns how to reconcile and meld the Dao and de. Human beings are said to be born of heaven and earth and therefore are modeled after both.

Ziran is the concept of being at all times in harmony with the Dao. The Dao de Jing describes the ideal Sage King as someone who understands ziran.

He who knows much about others may be learned, but he who understands himself is more intelligent. He who controls others may be powerful, but he who has mastered himself is mightier still.

Wuwei is a complex concept which is understood not as purely a passive form of non-action but as effortless action.

Although much uncertainty remains around the authorship and the dating of what we today know as the Dao de Jing, there is no doubt of its enormous influence on Chinese culture. Throughout Chinese history a large number of commentaries have been devoted to it. In 1973 the discovery was made of two Dao de Jing manuscripts at Mawangdui Hunan, China, found in a tomb that was sealed in 168 BCE. In 1993 another tomb dated approximately 300 BCE was excavated at Guodian, Hubei province. It yielded some 800 bamboo slips, some of which are inscribed with characters that match the text in the Dao de Jing.

The debate over what the Dao de Jing represents will probably never end. Some people say it’s a mystical text. Others claim that it is a work of philosophy and some people claim it to be the text of a religion. It remains open to diverse interpretations.

Mozi (480–390 BCE)

The Shi (or Xie) were the lower aristocracy. Many were specialists in administration as well as scribes. The Chinese classics such as the Classic of Documents were compiled and recorded by this class of minor nobility. Some of them had formerly fought wars in the Chariot units until this style of warfare became outmoded. Many Shi became unemployed during this time of social change and sought work in the new power centers. Increasingly rulers sought the advice of military experts among the Shi. Among them was a man known as Mozi, the founder of Mohism.

“Others must be regarded as the self” was Mozi’s version of the Golden rule.

Mozi preached active nonviolence. He saw the Zhou dynasty as elitist and the rituals of the li he viewed as a waste of effort. Mozi made the pragmatic observation: if all, including the poor, practiced the elaborate rites and sacrifices, the economy would fall apart. It was very wasteful and it did not help people here on earth. The Mohists put forth a concept that became important in early Chinese philosophy. It is known as fa, a model of behavioral standards based on the old Sage Kings. These they compared to instruments used in the world, such as the compass or rulers that craftsmen used to guide their work.

One important development by the Mohists was a move away from the traditional style of the analects (sayings of Confucius), which they thought fuzzy and not logical. Mohists argued their points logically and systematically.

Mozi was for a time more highly regarded than Confucius, perhaps because his message of peace was so timely during the warring states period. In 319 BCE Mozi became an official in the state of Qi.

Yangzi (440–360 BCE)

Yangzi (Yang Zhu) was an early Daoist teacher identified with naturalism as the best means of preserving life in a decadent and turbulent world. He may be said to have been a rational hedonist living by the creed of “Every man for himself.”

The Yangists challenged the Confucians and Mohists and rejected the traditional ritual order. The old rituals said that a person’s life was not his own, but Yangists argued that one must preserve one’s own life above all and do only that which came naturally. All beings have a survival instinct, animals relied on their strength but man should rely on his intelligence; to use strength against others would be despicable. Public life was external and ought to be considered mainly in terms of its risks. It is never secure and when it becomes clearly dangerous to seek political office, one had a duty to protect one’s own life by leading a humble, private life, and to refuse to put one’s own or another’s life at risk.

Zhuangzi (370–311 BCE)

Zhuangzi (Chuang Tzu) was a Yangist and hermit associated with the Mohist, Huizi. The two appear as friendly rivals in the Zhuangzi, an anthology of texts dating from 400–200 BCE. The first seven chapters of the text consists of stories, anecdotes and parables, often called the Inner Chapters, that question conventional wisdom asking whether reason and logic is of much value in trying to understand the Dao.

Zhuangzi taught that enlightenment comes from the realization that everything is one and the Dao is limitless and that words cannot describe it. He said that words are like a fish net: once the meaning is caught, one should forget the words, just as the net is only useful for catching the fish, but can be put aside once the fish has been caught. He thought that the world is flux. and we must learn to adapt.

When Zhuangzi was about to die, his disciples signified their wish to give him a grand burial. “I shall have heaven and earth,” he said, “for my coffin and its shell; the sun and moon for my two round symbols of jade; the stars and constellations for my pearls and jewels; will not the provisions for my interment be complete? What would you add to them?” The disciples replied: “We are afraid that the crows and kites will eat our master.”

Zhuangzi replied: “Above, the crows and kites will eat me; below, the mole-crickets and ants will eat me; to take from those and give to these would only show your partiality.”

Meng Ke or Mencius (370–288 BCE)

Meng Ke, known as Mencius in the West, was born only about eighteen miles from Confucius’s birthplace. He is probably best known for the view that human nature is innately good. Mencius thought that the senses could lead people astray because the senses operate automatically. He saw it as his duty to combat misguided teachings such as Mohism and Yangism as they could do the same.

Mencius was a Confucian who had an ambition to serve in government but was never able to do so successfully. He finally gave up and resolved to write a book about his recommendations for the rulers who wanted nothing to do with him. The main text attributed to Mencius, The Mengzi, was probably compiled by his disciples and later edited by others, leaving us the surviving text.

Mencius emphasized four ethical attributes: ren (benevolence), li (observance or rites),yi (propriety), and zhi (wisdom).

Mencius perpetuated the concept of the transformative power of a person that had cultivated himself and become a junzi, a fully mature person. He saw this concept as a natural basis for government: the ruler must be fully evolved and practice ren to retain the loyalty of the people.

Xunzi (340–245 BCE)

Xunzi was a Confucian synthesizer who thought that all the disparate schools of thought each had something to offer. Like Mencius, Xunzi believed that good governance could only arise around a fully realized person. He was repulsed by the materialism and raw ambition that defined the age. Xunzi experienced, firsthand, the effects of applying the legalist system on a statewide level while visiting the state of Qin. Xunzi was impressed with how well Qin was functioning. This fact challenged his belief that true government could only be based on the ren of a just ruler. Nevertheless, Xunzi never lost faith in that vision. He learnt from the legalists that people needed guidelines to be able to reform.

Xunzi held the view that knowledge depended on the mastery of fa (behaviors and standards modeled on the ancient Sage Kings). He writes in book eight: “The Way (the Dao) is not the way of heaven, and it’s not the way of earth: it is the way for guiding people, it is what gentlemen use as their way.”

Xunzi made a distinction between natural phenomena and the results of human effort. He thought that the success or failure of human effort depended on how the individual or group responded to nature. He taught that ancient sages had established The Way and that there was no need to adapt The Way to current circumstances. He opposed superstition and did not believe that worldly expertise was of much value. He argued that military success did not depend on strategy or tactics but on retaining the support of the population by ruling in a virtuous manner.

To Xunzi education was especially significant. He saw education as a process of accumulation; of individual steps that in sum total would bring one to the desired destination.

Legalism

Legalism, which was in direct opposition to Xunzi’s worldview, also emerged during the Warring States Period. Some rulers turned their back on Dao, relying instead on advisers from the emerging merchant class and from a new school of thought: the school of legalism. This school originated with political scientists known as the men of method. They believed that law and order was paramount in creating a well-functioning and efficient state, since people could only be dissuaded from acting selfishly if they were controlled. Once law and order were established, correctly implemented and backed by a harsh penal code, a just, prosperous and contented society would prevail.

In The Great Transformation Karen Armstong says, “The Legalists had made the important intellectual transition from the person-to-person government of feudalism to an objective legal system, which was not unlike the concept of law in the modern west, except that in ancient China the law was not designed to protect the individual but to achieve control from above. … it was not a Daoist sage but the Legalist state of Qin that ended the violence of the Warring States and unified the empire. This spectacular success seemed to prove that universal kingship could not be achieved without recourse to military power. It brought a peace of sorts, but spelt the death knell to the Axial hopes for morality, benevolence, and nonviolence. Under the empire, the Axial spiritualities would effect a synthesis and transmute into something quite different.”