The Success of Pauline Christianity

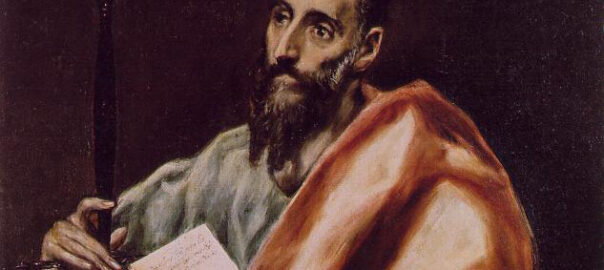

St. Paul by El Greco, Wiki Commons

“As evolving creatures, the problem is not that we have fallen, but that we are not yet fully human. We are not sinners, the church got that wrong; we are rather incomplete human beings.” Rev. John Shelby Spong, The Fourth Gospel: Tales of a Jewish Mystic

As Robert Doran (Prof. of Religion, Amherst College) notes in his book Birth of a Worldview: Early Christianity and its Jewish and Pagan Context: “Among the scores of religious sects that offered eternal hope or present ecstasy to the diverse peoples of the Roman empire in the middle of the first century, Christianity was not conspicuous. An impartial observer, asked which of these cults might someday become the official religion of the Empire, even a world religion, would perhaps have chosen Mithraism. He certainly would not have named the inconspicuous followers of a crucified Jew.”

Paul is certainly pivotal to the spreading of early Christian faith among the Gentiles. He and others did this through relentless effort, skillful marketing, and a willingness to adapt, compromise and absorb traditions and predispositions of potential converts. In addition, unlike Mithraism, which had become the official religion of Rome, Christianity was inclusive; it appealed to poor people who felt alienated by mainstream religions and to women who were excluded from Mithraism.

Why Did Christianity Grow So Rapidly during Its Early Centuries, and Why Has It Become the World’s Most Successful Religion Today?

In his book Religious Evolution and the Axial Age: From Shamans to Priests to Prophets, the sociologist Stephen K. Sanderson says that the reason was simple and backed by the findings of many scholars: Christianity provided people with a “better offer” than any of the other religions. To summarize:

1. Its message was simple and easily grasped. It was an inviting religion that was easy to follow.

2. The simplest and most appealing idea was its focus on a personal savior, a figure already familiar in the Mediterranean world.

3. Christianity’s God was like the God of Judaism, but it had Jesus, the Son of God, who was personal and very approachable. Christ died for our sins, and acceptance of Christ provides everlasting life.

4. Judaism was a very demanding religion, but Paul said that it was no longer necessary to observe the strict requirements of the Jewish Law (e.g., circumcision, kosher dietary practices, reading and comprehending the Torah). Christianity was demanding, but not as demanding as the religion from which it arose.

5. Its scriptures (the Bible) consisted of narratives about people and events that were clearly expressed.

6. It welcomed converts on a very egalitarian basis; anyone could become a Christian and enter the Kingdom of God.

7. A Christian church functioned much like a family in offering personal support. Other religions at the time did not create the kinds of networks providing support for their members.

8. Christianity not only offered a compensatory afterlife, but also rewards in this world. It made a miserable life less miserable.

9. Christianity emphasized “unreciprocated altruism” and “unconditional benevolence” toward outsiders to a degree not found in any other religion. It stressed nursing the sick, feeding the hungry, and clothing the naked. It set up orphanages, hospitals, almshouses, and so on, on a greater scale than any other religion.

10. Because Christians nursed the sick, especially during major epidemics, the sick were more likely to survive than non-Christians, and so their relative numbers within the population grew regardless of new converts. Pagans would have noticed that Christians were more likely to survive, and this would have motivated a significant number to convert.

Most of these same characteristics are still fundamental to Christianity and thus have the same appeal to people today. The fact that Christianity is a highly proselytizing religion that has directly sought converts has also played an important role.

Persecution

In the pre-Christian Roman world, the gods were actively involved in all aspects of both social and political life. It was the gods who had made Rome the great empire that it was, so while Christian beliefs could have joined the many that circulated around the empire, Christian monotheism and its intolerance of other religions was perceived as a threat to the Roman State and society at all levels.

Because of this, as writings in the Acts and Letters of the New Testament show, Christians were always vulnerable. The Emperor Nero (54–56 CE) blamed the conflagration of the city of Rome on Christians. Christians were at the mercy of local Roman officials who could handle things in whatever way they wished. The correspondence between Pliny the Younger and the Emperor Trajan, early in the second century, reveals that Christians under his jurisdiction were being tortured – at that time believed to be the best method of extracting the truth. Suspected Christians were required to disprove their affiliations “by worshipping our gods”; if they did so, they were acquitted.

Early Christians were meeting together in private homes, usually in the evenings since most had to work in the daytime. Because of this, rumors spread that they were engaged in all sorts of scandalous behavior. But even when faced with death, many Christians entirely refused to perform even minor cultic acts that might help to placate the gods and so maintain sociopolitical stability in the empire.

In the mid-third century, the Emperor Decius, when faced with upheaval from multiple sources including barbarians invading, economic instability and threats of assassination, realized that the gods needed to be worshipped with greater force. He issued an edict that required everyone in the empire to participate in the cultic act of sacrifice.

J.B. Rives notes in his article, “Decree of Decius and the Religion of the Empire,” in The Journal of Roman Studies, that “It is thus not surprising that before Decius’ decree on universal sacrifice, there had been no centrally organized persecutions of Christians: it was only when a ‘religion of the Empire’ had been defined and its boundaries set that there could be a systematic persecution of people who transgressed those boundaries.”

Decius was killed in battle in 251 CE and Valerian, who took his place, was the first to sponsor an empire-wide persecution. But his reign and the edict were short-lived. His son Gallienus became emperor and rescinded the edict. Christians enjoyed 43 years of peace in which their numbers grew exponentially.

Then in 303 CE, the Emperor Diocletian, under pressure and fearing a threat to the Roman state, issued an edict that declared an empire-wide persecution that lasted for about a decade: those Christians who refused to worship or even tolerate the gods had to be destroyed. Their places of worship, scriptures, rank and lives were to be destroyed or the people enslaved. A further edict was issued that year that ordered the arrest and imprisonment of all bishops and priests. A short amnesty was declared later on in the same year but rescinded in 304 when collective and universal sacrifice was ordered under pain of torture and death.

Given that there was no authority to ensure that these decrees were carried out, enforcement was not universal. There is no way to know how many Christians were imprisoned or died, but modern historians feel that numbers like 100,000 were exaggerations. In his book, The Triumph of Christianity: How a Forbidden Religion Swept the World, the New Testament scholar Bart Ehrman says his research indicates it was “possibly hundreds of people, although almost certainly not many thousands. We do know that, in the end, the Christians came out on top. Constantine converted, and with one brief exception all the emperors to follow were Christian. There would never again be an official Roman persecution of the Christians.”

In 312, following a vision, emperor Constantine ordered a Christian symbol to be painted on his soldiers’ shields. Under this emblem he won a battle against Maxentius and his forces at the Milvian Bridge on the Tiber River. Constantine converted to Christianity, and the following year as Western Roman Emperor, he and Licinius, the Eastern Roman Emperor, issued the Edict of Milan, which proclaimed religious toleration in the empire and gave Christianity legal status, granting Christians restoration of all property seized during Diocletian’s persecution (303–311 CE).

Constantine’s eventual victory over Licinus influenced the rise of Christian- and Latin-speaking Rome and the decline of Pagan and Greek-speaking populations. He made Byzantium the capital of the East and renamed it Constantinople (Constantine’s City). It became the largest and wealthiest European city and was instrumental in the advancement of Christianity.

According to Stephen Sanderson, the converted Christian Constantine behaved in a traditional pre-Christian way: rather than destroy paganism as would happen later, he gave it equal standing with Christianity, and he himself continued to worship pagan gods.

In Religious Evolution and the Axial Age, Sanderson says, “As late as the middle of the fifth century much of the population of the Roman empire was still pagan, and so paganism did not suddenly vanish (Brown, 1998; Stark, 2006). And because Christianity shared some pagan ideas and practices, it could incorporate them, and, indeed, did so. Some traditional pagan rituals for celebrating holidays were absorbed into Christianity, including candle lighting, bell ringing, festive dancing, and singing. However, these practices were not taken over unaltered, but were Christianized. The celebration of Easter also had deep roots in the mystery religions. Something like Easter had been widely practiced by pagans. The name itself may have been based on the Saxon goddess Eostre, but there were other goddesses with similar names. Pagan Easter was celebrated in the spring; indeed, the Old English word for spring was eastre.”

Ehrman sums up the situation: “Early Christians devised the notion of the separation of church and state. This was a view that made considerable sense to Christians of all types so far as we can tell—until the Roman emperor became Christian. Then suddenly the idea seemed to vanish. After Constantine began showering favors on the church, the political views of the apologists were taken off the table. Now it made obvious sense to Christians for the emperor and all his underlings to support, promote, and advance the cause of religion. … this imperial shift—not in policy but in allegiance—had a devastating effect on the pagan world. The tables had turned. Now it was Christians, with their exclusivist views about true religion, who were in charge. The persecutors became the persecuted.”

Council of Nicaea—Origins of the Trinity Doctrine

At the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE, in which some 300 bishops from all over the empire assembled to discuss the state of the church, important doctrines were developed to counter “heretic” ideas. The core dogma of the Christian faith was developed and the concept of the Holy Trinity as the supreme deity was officially adopted.

We are back to persecution again, but this time the perpetrators are Christian and the victim, from the perspective of our human journey, was the Ancient Classical world. In 385 CE Theodosius the Great made Christianity the official state religion of Rome, he outlawed oracle sites and completely banned worship at pagan temples. Pagan sites great and small were plundered, repurposed, or simply buried and forgotten.

The Christian Church was now a powerful and far-reaching institution. Thus, Pauline Christianity survives today with its influences of ancient pre-Axial religious beliefs and rituals intact. It continues to offer emotional stimulus and release, automatic cleansing and redemption through quasi-magical ritual, and spectacles of a misrepresented sacrifice and passion.

Yet modern Christianity, to some extent, offers both Axial and pre-Axial traditions. While Pauline Christianity survives at the expense of our individual responsibility, we can decline to accept it and become actively involved in our own ethical and spiritual development. It is exactly this kind of individual responsibility which comes through very clearly in the teachings of Jesus preserved, for example, in the Gospel of Thomas and elsewhere.

Parable of the People with a Higher Aim

Imam El-Ghazali relates to tradition from the life of Isa, ibn Maryam, Jesus, Son of Mary.

Isa one day saw some people sitting miserably on a wall, by the roadside. He asked: “What is your affliction?”

They said: “We have become like this through our fear of Hell.”

He went on his way, and saw a number of people grouped disconsolately in various postures by the wayside.

He said: “What is your affliction?”

They said: “Desire for Paradise has made us like this.”

He went on his way, until he came to a third group of people. They looked like people who had endured much, but their faces shone with joy.

Isa asked them: “What has made you like this?” and they answered: “The Spirit of Truth. We have seen Reality, and this has made us oblivious of lesser goals.”

Isa said: “These are the people who attain. On the Day of Accounting these are they who will be in the presence of God.”

Idries Shah, The Way of the Sufi

In the series: Jesus and the Origins of Christianity

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

Sons of God and Virgin Births

The concepts of divine paternity and virgin-birth were familiar ones to people of the first century Roman Empire and throughout the ancient world.