The End of the Caliphate and the Christian Reconquest

Despite the decline of Muslim rule in Spain starting in the 11th century, Arabic works and knowledge continued to spread into Christian Europe. In fact, as Maria Rosa Menocan writes in The Ornament of the World, the intellectual influence of Arabic-based learning and culture waxed in almost direct proportion to the political waning of what remained of al-Andalus.

Besides Spain, there were other pathways of transmission and translation between the Christian and Muslim worlds. Venice traded with the Muslim world for centuries. We owe our coffee habit to the importation of the beverage into Europe from the Arab world by Venetian merchants. Sicily, which in the twelfth century included the entire southern half of Italy, remained as religiously tolerant under Norman rule as it was under Islamic rule. There Hebrew, Arabic, Latin and Greek were recognized as official languages and Sicily’s capital Palermo was one of Europe’s most important cultural centers.

The Madinat al-Zahra library was destroyed in 1009, when Cordoba was besieged by the Berbers. The Umayyad caliphate ended in 1031, which led to the formation of multiple city-states, or taifas. The Christian ruler Alfonso VI conquered the taifa of Toledo in 1085, an act that also provoked an invasion from the Berber Almoravids, which Alfonso would spend the remainder of his reign resisting. Mutamid, the last ruler of the taifa of Seville, sought help from the fundamentalist Muslim Almoravids, and for the next 150 years, the taifas came under their control, followed by that of the Almohads – preventing the fall of Al-Andalus to the Iberian Christian kingdoms.

Eventually the Almohads were defeated by Ferdinand III of Castile, with Cordoba falling in 1236, Valencia in 1238 and Seville in 1248. The last Arabic ruler in Spanish territory was Abu abd Allah Muhammad XII (also known as Boabdil) of the Emirate of Granada, who formally gave up his sovereignty and territories to the Crown of Castile in 1492. Under Ferdinand II and Isabella I of Aragon and Castile, Muslims were pushed out of Gibraltar, and conversions to Christianity were forced on Jews and Muslims alike.

The Toledo School of Translators

“Far from being peripheral or secondary to the principal concerns and activities of those who remained speakers of Latin . . . the dominant world of the age in which Arabic was the classical language was rarely out of mind and never out of reach, and the effects of such contacts were widespread and central. They were often the intellectual lifeblood of northern European centers.” (Menocal, The Arabic Role in Medieval Literary History)

Were it not for Islamic learning, Western thought would have been limited to fragments patched together by western teachers such as Boethius, Marianus Capella, Bede and Isidore. The works of Plato and Aristotle would have been virtually unknown. Instead, from the tenth century on, European scholars traveled to Spain to study and “Through trade contacts and through political presence in Spain and Sicily the superior culture of the Arabs gradually made its way into western Europe.” (Montgomery Watt, The Influence of Islam on Medieval Europe)

Once the taifa of Toledo was under his control, Alfonso VI of Leon and Castile promised the Muslim inhabitants that they could continue their religious practices, though he exacted heavy financial tributes in return. His physician was Granada-born Joseph Nasi Ferruziel, a prominent Jew who owned large estates around Toledo, and for a short while religious tolerance in the region was such that even the church of Santa Maria la Blanca was shared, with Muslims using it on Fridays, Jews on Saturdays and Christians on Sundays.

From 1126 to 1151, some three centuries after the Translation Movement in Baghdad, Archbishop Raymond of Toledo founded Toledo’s School of Translators at the city’s cathedral to promote the translation of philosophical and religious works from Arabic into Latin.

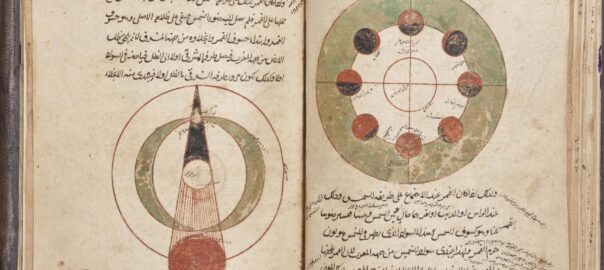

Ferdinand III’s son Alfonso X, known as “the Learned” and “the wise king,” reigned from 1252 until his death in 1284. He reoriented the work of Toledo’s School of Translators so that it translated works from Arabic into Castilian rather than into Latin, thus laying the foundations for the spread of the modern Spanish language. Alfonso sponsored the creation of the Alfonsine astronomical tables, updating the tables that had been generated in Baghdad and had been translated by Gerard of Cremona from the Arabic. As Nightingale points out in Granada: A Pomegranate in the Hand of God, this was an impressive example of the fruits of convivencia, “the work of Arabic astronomers [sponsored by] a Christian king, refined and extended by two Jewish scholars.”

In the first quarter of the twelfth century, key locations of translation work included cities in Spain and such as Barcelona, Tarasona, Segovia, and Pamplona. In Sicily Roger II and his son William I preserved Arab and Greek culture and translations from Greek and Arabic into Latin were made by such notable figures as Henry Aristippus, Admiral Eugenius, the monk Filagato Ceramide and Adelard of Bath. Beyond the Pyrenees were translation centers at Toulouse, Beziers, Narbonne, and Marseilles. Eminent translators include Plato of Tivoli, Robert of Chester and Herman of Carinthia with his pupil Rudolf of Bruges; Hugh of Santalla in Aragon, Robert of Ketton in Navarre and Robert of Chester in Segovia.

The Christian European world came face-to-face with the Islamic world in a series of religious wars known as the Crusades. From 1096 to 1291, Christian knights, soldiers and commoners reaching the Islamic world were astounded to discover that the so-called infidels had a more sophisticated and developed civilization than their own. Islamic cities had hospitals, sewers and irrigation; their thinkers seemed more skilled, learned and intelligent than their European counterparts. Islamic scholars such as Montgomery Watt note that the shame this caused accounts for the historical errors and omissions that, until recently, ignored the Arab contribution to Western thought. “Distortion of the image of Islam among Europeans was necessary to compensate them for this sense of inferiority.” (The Influence of Islam on Medieval Europe)

Khalili notes that apart from Aquinas and the English William of Occam (c.1288–1347), “there were very few other Christian scholars whose achievements could rival their Muslim counterparts until the end of the fifteenth century and the arrival of Renaissance geniuses such as Leonardo da Vinci. By that time, European universities would have contained the Latin translations of the works of all the giants of Islam, such as Ibn Sīna, Ibn al-Haytham, Ibn Rushd, al-Rāzi, al-Khwārizmi and many others. In medicine in particular, translations of Arabic books continued to be studied and printed well into the eighteenth century. Among the European scholars influenced by their Islamic counterparts before them were Roger Bacon, whose work on lenses relied heavily on his study of Ibn al-Haytham’s Optics, and Leonardo of Pisa (Fibonacci), who introduced algebra and the Arabic numeral characters after being strongly influenced by the work of al-Khwārizmi.”

In the series: The Journey of Classical Greek Culture to the West

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

Watch: Science & Islam

BBC full series with Jim Al-Khalili

The history of Islamic science and it’s subsequent spread through Europe.