Axial Age Thought:

Buddhism

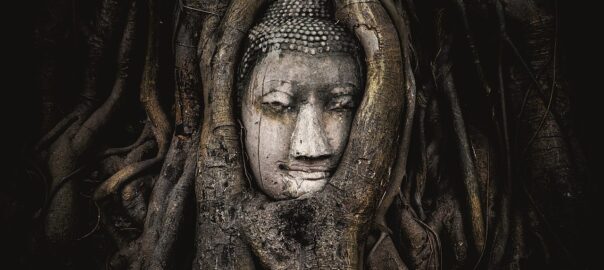

Image: Siripatwongpin for Wikimedia Commons.

Siddattha Gotama—the “Awakened One”—advised pupils not to accept anything simply because it is traditional or comes from a sacred text or charismatic teacher. He emphasized the quality of mindfulness—awareness without judgment of mind, body, and environment. He taught that spiritual attainment was no longer limited to certain castes, but possible for everyone, without discrimination based on gender, age, social status, or moral standing.

Siddhattha Gotama 490–410 BCE

During what has been called the second urbanization of north-eastern India, emerging small kingdoms caused upheaval in all areas: economic, social and religious. Brahmin priests no longer retained the level of prestige and power they had as Vedic rituals and religious traditions lost their value, and more people turned their focus inward. They sought to know the true nature of reality that was at the basis of religious practice and the very foundation of life.

Men and women of all castes gave up everything to live a life of meditation, yoga, contemplation, starvation, self-mortification and deprivation of all kinds, in order to find this freedom, self-knowledge and fulfillment. Known as Samanas, there were so many of them that they were regarded as a fifth caste. These ascetics and sages lived alone in caves or forests, or with their families in communities. They were supported by those who felt unable to do the same but who, by helping them, believed that they gained Karmic benefits.

One Samana was Siddattha Gotama (Siddhartha Gautama), who would eventually become known as Buddha—the “Awakened One.”

“Having it all is not Enough”—the legend of Siddattha Gotama

Siddattha Gotama, legend has it, was a royal prince whose father had protected him from any kind of suffering. From the time of his birth until the age of 29, he was given everything that one could possibly want: looks and riches, a beautiful wife, a healthy son. Then, at 29, he encountered sickness, old age, and death for the first time. Overcome by what he saw, Gotama recognized that all beings were subject to these things, no matter how much they had of worldly goods and splendor. He could no longer ignore the realities of life: suffering and death. Then he met a Samana who had renounced everything but appeared happy nonetheless, so, following his example, he left his home forever, and took up the begging bowl and staff of the Samana, to seek the end of his samsara, the constant cycle of births, deaths and rebirths. Tradition refers to this episode as the “Four Sights.”

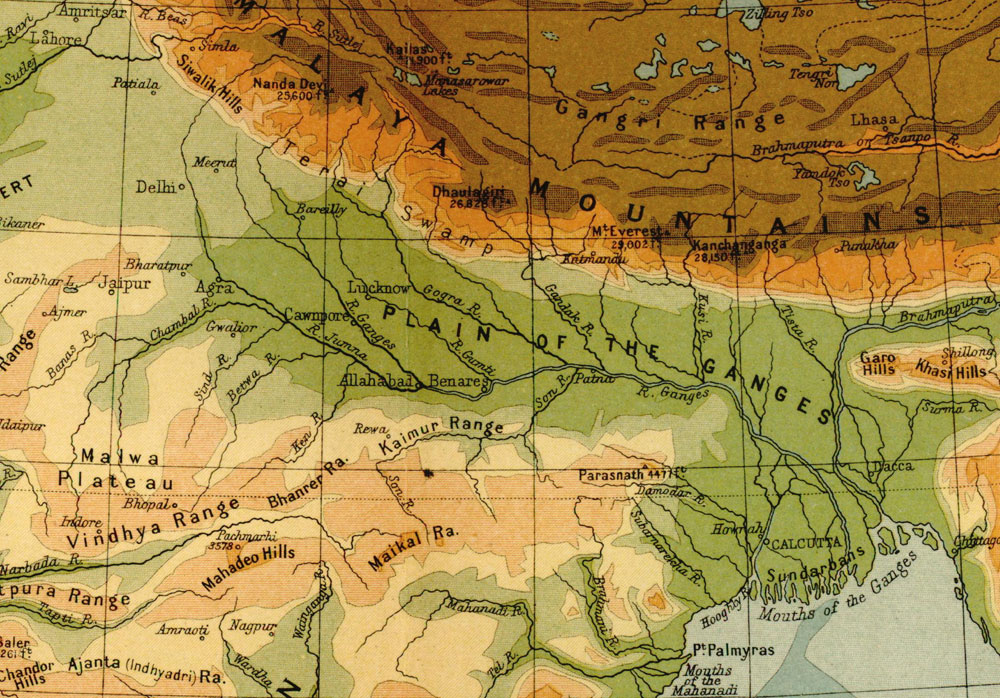

For six years Gotama practiced the ascetic arts, traveling throughout the cities of the Ganges basin, studying with teachers who could impart the disciplines that would end his samsara. He learned yogic meditation and other practices but refused to believe that the temporary states arrived at were the highest realization possible to man. He deprived himself of food until he became emaciated, but concluded that this method only intensified suffering, it did not release one from it.

He realized that neither the pleasures of life nor the ascetic practices of the Samana offered him the wisdom he sought. He needed to find a way between these two extremes—this he called the Middle Way.

According to the Buddhist tradition, Gotama sat beneath a huge tree that was later called the “wisdom,” or “Bodhi” tree and vowed not to leave it until he achieved the liberating knowledge he sought.

Unlike his teachers, whose practices focused on achieving extra-sensory perceptions of the mind, Gotama’s emphasis was on the quality of “mindfulness”—awareness, without judgment, of mind, body and environment. He remembered that as a child he had meditated and focused on his breath and that this had brought him a sense of both pervading calmness and awareness. He undertook a long and arduous period of meditation and contemplation that culminated in his acquiring deep insights into the human condition. Finally, in overcoming the temptations of the demonic Mara, he believed he did attain nibbana (or nirvana)—the understanding that liberated him from samsara.

“In that instance the knowledge and the vision arose in me, unshakable is the realization in my mind, this is my last birth.” At this moment he earned the title Buddha—the “Awakened One.”

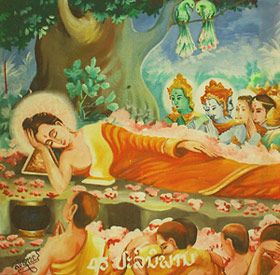

For 49 days, we are told, he enjoyed this liberation, and pondered whether he could teach others how to attain it. Finally, he traveled on foot to Benares to seek the five ascetics who had deserted him when he gave up the samsara way. They recognized that something had changed in him, and, following his Dhamma (Dharma: teachings), became the first arahants of Buddhism. Buddha taught for several decades throughout the cities of the Gangetic basin, building a community of followers. In 410 BCE, at the age of 80, he became mortally ill, his last words, tradition has it, being: “All compounded things are subject to decay, work out your salvation with diligence.”

The Four Noble Truths

Dhamma or the teachings of the Buddha—the truth that leads to liberation.

1. Life is suffering (Dukkha)—our desires and expectations do not conform to the reality of the world, which is in a constant state of flux (Anicca), so we experience Dukkha.

2. The origin of suffering is attachment—not only do we fail to know reality but we mis-know it. We attribute permanence to impermanence. The physical universe is constant change, but we know it as permanent—change is the only thing there is. Our ideas, the objects that surround us, and our perceptions, are all transient. Even our idea of “self” is a delusion since there is no permanent self Craving and clinging to these inevitably leads to suffering.

3. It is possible to end suffering in this life—Like the moksha in Hinduism, nibbana can be realized in life, through discipline and effort. Nibbana means freedom from troubles, worries, ideas, and the annihilation of the illusion of the self where one understands Dhamma—the Buddha’s teaching and becomes an arahant.

4. The path to cessation of suffering—The Middle Way—is a path between the extremes of clinging and aversion, both expressions of attachment, arriving at a state of complete equanimity. It is achieved through the Eightfold Path.

The Eightfold Path

Summa—“right,” or that which promotes the end of suffering has traditionally been divided into three sections:

Study—Cultivating Wisdom

1. Right Understanding: a person becomes acquainted with the basic principles of Dhamma, the Buddha’s teachings, and enters the path, gradually awakening an understanding of the wisdom he or she can attain at the end.

2. Right Intention: One contemplates the desire for all beings to be happy and free from suffering. One cultivates goodwill, harmlessness and non-attachment, avoiding tendencies towards greed, hatred and harm.

Ethical Conduct—Developing Moral Conduct

3. Right Speech: I will refrain from false speech—not only lying or slandering, but gossip, cursing, swearing or meaningless babble. I will communicate in kind, gentle and direct speech.

4. Right Action: there are five precepts of non-harming (ahimsa)—these are ideals that one vows to live by: to refrain from harming sentient beings; to refrain from taking what is not offered; to refrain from sexual misconduct; to refrain from false speech; to refrain from stupefying drink.

5. Right Livelihood: to earn a living in a way that benefits humanity.

Mental Development—Disciplining the Mind

By “mind” the Buddha meant the totality of thoughts, sensations, feeling and consciousness, that are experienced at each moment. The mind has great potential, but the undeveloped mind is like a wild horse: difficult to stay attentive, it craves stimulation, jumping from thought to thought, dwelling in the past or in the future, with thoughts that often cause anxiety or fear. When this undisciplined mind does pay attention to the present, it does so with opinions and emotional reactions rather than being in the present. To bring the mind under control is necessary, but it requires patience, skill, and persistent training.

6. Right Effort: since deluded thinking hinders the ability to understand the world, the student pays deliberate attention to developing positive thoughts that alleviate suffering and to letting go negative ones, he or she practices generosity and patience.

7. Right Mindfulness: taking meditative awareness into everyday life. Doing so can restrain the mind’s proclivity to make immediate judgments, reduce its tendency to need stimulation, and sharpen its awareness in the present moment.

8. Right Concentration: it is necessary to take time each day to practice meditative awareness.

These eight elements are symbolized by a wheel and practiced simultaneously, since the practice of one supports the practice of the others. The Buddha maintained that one could develop the virtues described as one would develop any skill, with regular practice.

Buddha did not want his teaching to be accepted on his authority. Anything can become an object of attachment, even his own teaching. He encouraged the individual to take responsibility for his own beliefs. For the Buddha, Karma was rooted in intentional acts, it was not absolute as in the Hindu conception. He advised that pupils should not accept anything simply because it is traditional or hearsay; or because it comes from sacred text, because it seems rational, logical, or comes from a teacher who is competent, or charismatic. He emphasized that one should check one’s views, test ideas, and guard against the possibility of bias.

Buddha emphasized spiritual self-sufficiency and responsibility, rather than depending upon the Brahmin priests. He taught that spiritual attainment was no longer limited to certain castes, but possible for everyone, without discrimination based on gender, age, social status, or moral standing.

He saw himself as a healer, not a god. He was never represented in human form until 300–400 years after death. When asked how he should be described, the Buddha said “Remember me as one who is awake.”

This story is an exemplar of his teaching:

The Mustard Seed

Once there was a woman named Kisagotami, whose only son died. With the dead child in her arms, she ran from house to house begging, “Please give me medicine for my son.” Seeing her, the people shook their heads in pity. “Poor Kisagotami, you have lost your senses. Your son is dead. He is beyond the help of medicine.” She, however, refused to accept this and went on wandering in the streets asking everyone she met for help. A gentle old man took pity on her and said, “Go to the Buddha. He will help you.” In haste, Kisagotami took her dead son to the Buddha and asked, “Is there a medicine to cure my son?” He looked at the closed eyes of the child and understood, “I will heal your son if you bring me a handful of mustard seed.” Joyfully, Kisagotami started off to get them. Then the Buddha added, “But the seeds must come from a house where no one has died.” Kisagotami went to every house in the city and asked for the mustard seed. “We have plenty of mustard seed,” everyone said. “Take all that you need.” Then she asked, “Has anyone ever died in this house?” “But of course,” she was told. “There have been many deaths here.” “I lost my father,” “I lost my sister,” “I lost my daughter.” “There are more dead here than living.” She could not find one house that had not been visited by death. Weary and with all hope gone, Kisagotami sat on a hilltop and watched the fires of the city flicker up and die out. Suddenly she came to her senses and said, “The lives of people flicker up and go out like fire. My son is not the only one who has died. Everyone dies. How selfish I am in my grief!” She buried her son amid the wildflowers and returned to the Buddha. “Now I understand your teaching,” she said, holding out an empty hand. Kisagotami joined the sanga (community) and became an arahant.