Featured Book

The First Word:

The Search for the Origins of Language

Christine Kenneally

Paperback edition 2008

Linguist and science writer Christine Kenneally traces the development of evolutionary linguistics from its early speculative history to its modern emphasis on genetics and computational modeling.

Along the way she enthusiastically spins narratives of the fractious professional debates between prominent individuals in the field, outlines major steps in human evolution, describes the anatomy of the human brain, details the cognitive difficulties of oxygen-deprived mountain climbers, and explains similarities and difference between human anatomy and that of other great apes.

How Animals Illuminate Our Past

Kenneally is most ardent when she describes research into animal cognition, and the efforts to teach various species some form of human language. She finds the human capacity for language not so remarkable in light of a new appreciation of the abilities and behaviors shared by many kinds of animals, and less extraordinary also because humanity has an inflated view of its own linguistic and cognitive potential. She favors the view that language ability evolved as an adaptation, involving many parts of the human brain and body, and that evidence of this adaptation can be found throughout the animal kingdom.

Many researchers believe that for language to have evolved, there first had to be a need to speak, as opposed to having language evolve suddenly and then finding there was a lot to talk about. In this view, language ability was not an accident, nor was it brought about by a sudden enabling mutation for grammar. If language ability evolved in the same adaptive way as most other abilities, then the search for the origins of language includes a search to uncover what was so advantageous to communicate. It is helpful in this search to study what goes on in the minds of nonlinguistic creatures.

to say their name, greet other dolphins,

and say good-bye.

Animals that demonstrate relatively advanced cognitive abilities suggest what the minds of our prelinguistic ancestors may have been like. Many species that demonstrate complicated thinking have a fair amount in common with humans – dolphins, elephants, and crows all have long lives, extended infancy, complicated systems of communication, and societies where individuals have distinct roles. Female elephants, for example, live years beyond their reproductive age and pass on learning to youngsters, such as how to interact with other elephants, as well as information about water holes or fruit trees.

Elephants also appear to use sounds like words. Researchers found that individual elephants produce distinct sounds for different purposes, like greeting a fellow member of the clan they haven’t seen for a while. Similarly, dolphins use echolocation clicks and purposeful types of whistles, and appear to name themselves with a “signature whistle.” Whenever they meet another dolphin they produce a distinct, individual sound, which develops in their first year of life. And there is evidence that dolphins exchange signature whistles when separating. A team of researchers in Scotland found that wild dolphins recognized that a signature whistle referred to a particular dolphin even when its voice was completely distorted.

Vervet monkeys make three different word-like alarm calls when they see a threat from ground, tree, or air, warning their group to take appropriate defense. Some researchers think that these alarm calls may be “protowords,” a primitive form of language. When animals make alarm calls, they are connecting a particular sound to a referent in the world. Every species of animal that researchers have studied so far can link sound and a referent. Humans have built on this ability by using this ancient platform for sound and referent to evolve human language.

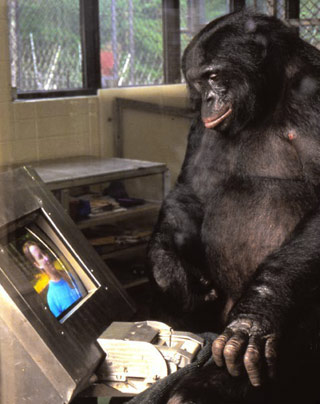

Captive Bonobos Learn Language Comprehension

Language is built in two levels of construction. At the first level, sounds from the set comprising the language – its phonemes – are combined into meaningful sounds known as morphemes. There are for example about 44 phonemes in English (depending on the dialect), which are combined to make parts of words and words themselves, such as “micro” and “wave.” Morphemes are found in birdsong, in the songs of whales, and in other animal vocalizations. The morphemes in these songs recur repeatedly, but perhaps surprisingly, no animal vocalization, not even birdsong, has the range of sounds that humans possess.

At the next level, morphemes are combined into phrases that are usually intended to convey meaning. Linguists call this syntax – the rules for combining words in a recognizably correct manner. As Chomsky noted, we can produce syntax separately from meaning, as when one constructs the grammatically correct but meaningless, “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.”

Until recently, it was believed that only humans could make use of the structural rules of syntax, but different types of syntax have been observed in the communication of a number of primate species, including chimpanzees and gibbons. Gibbons arrange sounds into structured vocalizations that are quite different from those of most other primates in order to produce complex songs, used to communicate up to one kilometer in distance. What is important about these gibbon utterances is that the same set of sounds has two different meanings to a gibbon when ordered in two different ways. The simple structural rules used by these primates in the wild contradict the idea that creating meaning with a defined structure – for example, subject, verb, object – is a special human ability.

To better understand the potential that animals have for language comprehension, efforts have been underway for several decades to teach human communication to animals in captivity, with startling results. Numerous chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas have acquired a facility with American sign language to a degree that allows them to converse at the level of a young child. (Kenneally states their achievements are on a par with children as old as four, which is significantly older than the consensus estimate of age two and a half years. Much cognitive development occurs in children between these ages.)

Sue Savage-Rumbaugh began teaching language to bonobos in the 1970s. She maintains that the best method is to teach them indirectly, much as young children learn language, by having them hear it all around them. Young bonobos are raised in a language-rich environment by regularly being spoken to during feeding, playing, and grooming, rather than being drilled in repetitions of a word while pointing to the sign for it on a picture board. The result, Kenneally writes, is that the bonobos can, in addition to making simple declarations, converse about intentions and states of mind.

These bonobos demonstrate creativity in their use of words. For instance, some of them spontaneously combine single words that they have already learned to create new words, such as linking “water” and “bird” to form “waterbird,” meaning a duck. Savage-Rumbaugh’s star pupil, a young male named Kanzi, could combine symbols to instruct what he wanted her to do. Savage-Rumbaugh has written that Kanzi’s immersion into a language-rich environment enabled him to acquire all of the mental components necessary for language acquisition and production.

The last common ancestor of humans and bonobos lived six million years ago. When Kanzi demonstrates the ability to produce or comprehend language at the level of a young human child, it suggests that humans and their closest relatives were bequeathed a common set of skills that enabled them to produce something like language as we know it. It makes sense to assume that our common ancestor evolved the trick of combining sounds – even in a limited way – to create meaning. Thus the foundations of language existed long before the genus Homo arrived on the scene.

Language, the Brain, and Genetics

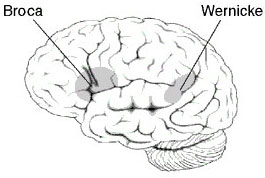

critical role, but language ability

is distributed throughout the brain.

A generation ago, it was commonly accepted that language ability is located almost entirely in Broca’s and Wernickes’s areas on the left side of the brain. This view was based upon research into the study of language dysfunction in individuals whose brains had been damaged by trauma or disease. But according to Kenneally, this belief that the left brain is responsible for language is now superseded by the present understanding that language and other higher mental abilities are distributed throughout the brain.

To be sure, once the human brain has matured, the way language function is distributed across the brain is not random. Particular areas take on distinct parts of the overall task of perceiving, understanding, and producing language. But when the parts of the brain that are best suited for language acquisition fail in young children, other parts can sometimes assume the tasks of the damaged regions, restoring a child’s language facility to normal levels. This property of how brain tissue can be re-purposed is called plasticity.

The plasticity of brain organization is not just a human property. The brains of apes change when the creatures have been moved from a standard laboratory setting to a more stimulating environment. An autopsy of a language-trained ape revealed it possessed a brain much larger than average size for its species, and Savage-Rumbaugh maintains that this growth in size was the result of its learning experience. Her research has concluded that primate brains are just as sensitive as humans to small increases in environmental complexity.

While apes in the wild do not sign to one another, and wild parrots do not talk, Kenneally suggests that brain plasticity accounts for their more sophisticated language abilities in captivity, that is, the captive brains grow in response to the increased stimulation provided by constant human contact. In this view, wild animals would derive no benefit from the greatly increased expenditure of mental effort that language requires. There is an enormous difference, Kenneally writes, between being able to speak or not, but this difference may result from circumstance and not from large differences in brain physiology.

She likewise dismisses differences in genetics that purport to account for an innate grammar facility in humans. Much attention has been focused on the discovery that a specific gene, called FOXP2, has a profound effect on language ability. This has prompted speculation, along lines suggested by Chomsky, that the evolution of this gene accounts for the development of language as a mutation that arose without adaptive precedent. Since the emergence of language is synonymous with the appearance of cognitively modern humans between perhaps 50,000 to 80,000 years ago, presumably FOXP2 developed in its present form at that time.

Kenneally rejects this view for several reasons. For example, the human version of FOXP2 is unique to H. sapiens, but biologists have found that the gene is 98 percent the same in humans and songbirds. The avian version of the gene seems to play a significant role in the learning and production of bird song, with the expression of the gene increasing in certain brain areas at the developmental stage when the birds are learning to sing. Mature birds with a greater expression of the gene tend to vary their songs more than others. This indicates that human communication depends on the same genetic foundations as does communication by other animals.

As to the sudden appearance of FOXP2 as a gene for grammar, Kenneally states that Neanderthals, whose last common ancestor with H. sapiens lived at least 400,000 years ago, possessed a version of FOXP2 that was essentially identical to that found in modern humans. Whether Neanderthals could speak or not is unknown, but this is evidence that language ability evolved gradually in the same manner as other cognitive abilities. While some researchers maintain that some genes may exist for the purpose of encoding grammar, Kenneally believes that this idea has been proven false.

Further investigation into the role of FOXP2 may shed light on the evolution of language in an unexpected way. FOXP2 also affects various motor skills, and research has shown that when children acquire language there is an important connection between speaking words and using gestures to add meaning. A consensus appears to be forming among a number of researchers that human language evolved from the volitional use of gestures by great apes for communication.

The work on gesture has demonstrated both a continuum that connects human and ape communication and significant differences between them. In our evolutionary history some individuals must have been born with a greater inclination and ability to collaborate. These individuals were more successful and bred more offspring. Chimpanzees are goal oriented, they cooperate when it is beneficial or expedient to do so. Humans prefer and enjoy collaboration and it is in our desire to connect with others that the symbolic communication of language is found.

About the Book’s Author: Christine Kenneally was born in Australia and received her Ph.D. in linguistics at the University of Cambridge. She has written about language, science, and culture for publications such as The New Yorker, The New York Times, Scientific American, and Slate.

Numbers and the Making of Us

Counting and the Course of Human Cultures

Caleb Everett

Numbers, says Everett, are a key linguistic innovation that has distinguished our species and reshaped human experience.

In the series: The Evolution of Language

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

Chimps “Talk” to Each Other About Their Favorite Fruit Trees

IFLScience!

Researchers studying wild chimpanzees have discovered that our closest living relatives convey information about different foods and the size of fruit trees to each other.