Thought and Language

Camille Corot, Young Girl Learning to Write. Wikiart.org

Recursive thinking—the ability to embed ideas within other ideas—is the underpinning of human communication. Understanding more about how this ability evolved may help us unlock the complex challenges we face today.

All humans are born with the ability to speak and think recursively. But our individual languages are unique, adaptive tools, each one shaped and modified by the environment in which it developed. The language we are born with and the way we write it influences how we perceive time in space and how we remember events.

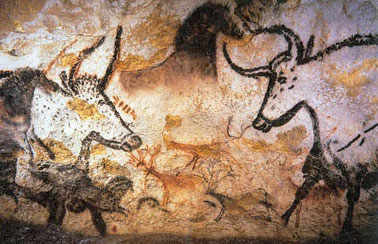

The symbolic creations of the Upper Paleolithic period that we marvel at on cave walls represented a new ability to express experiences and ideas exterior to oneself in two-dimensional art. This new ability would lead to our complex writing and numerical systems and to the development of the numerous external memory records and cultural products which proliferate in the world today.

Thought, Brain Size, and Physiology—an Evolutionary Feedback Loop

These transformations required an acceleration in brain development which Merlin Donald and others believe can be explained by the brain’s “plasticity”—its potential for functional adaptation. This quality enabled brain development to proceed at a rate far in excess of the relatively slow pace of genetic evolution.

The transition from speech to external symbols may well have caused a feedback loop where developments in language themselves stimulated biological changes, and these changes further changed our biology. A study led by anthropologist John Hawks concluded that in the last 5,000 to 10,000 years, as agriculture was able to support increasingly large societies, the rate of evolutionary change in human genetics was more than 100 times faster than before. And the genes related to brain development were evolving fastest.

Thanks to the work of Sue Savage-Rumbaugh and others, we know that captive apes who have been taught sign language can communicate about past events, future plans and abstract ideas with their trainers, as well as interpret pictures, enjoy humor, and display other human-like mental skills.

Captive gorillas may acquire new modes of thinking in the process of learning sign language, but it’s unlikely that these developed exclusively because of the training. As we have seen, apes gesture intentionally; bonobos and chimps show some degree of future-thinking and mind-reading even in the wild. In these circumstances, thought does precede its expression. The language ability of apes may well be a protolanguage originally shared by our ancestors—a precursor of our own ability.

However, it is more than likely that only humans can remember countless episodes from the past, make numerous plans and continuously predict future situations. As we know from our favorite entertainments and, of course, from gossip, we are particularly interested in the lives of others. We need to communicate.

There is a distinction between what individuals can think about and what they can communicate. The question is how much do these two activities affect each other? Humans are born with the ability to speak. As infants we think and comprehend things about our physical world before we are able to understand specific words, and long before we can pronounce them.

Our brains grew larger as we developed an ability to express thoughts about the past and the future through mimesis, and from this evolved our unique ability for complex recursive thought. Recursion is our ability to embed ideas within ideas. In The Recursive Mind: The Origins of Human Language, Thought, and Civilization, psychologist Michael Corballis says the ability to think recursively is the primary characteristic that distinguishes the human mind from that of other animals.

Language as an Adaptive Tool

As our physiology continued to change we became able to produce a great variety of sounds, which then enabled us to develop speech and to create our communities’ languages. Just as the cries of chimpanzees about their favorite fruit trees developed in response to the ecological complexity of the Taï forest of Côte d’Ivoire in West Africa, human languages too are unique, adaptive tools, each one shaped and modified by the culture in which it occurs.

Michael Corballis claims that it is the recursive nature of our memory (our ability to remember multiple past events and imagine possible future ones)—coupled with our ability to gauge what is in the mind of other individuals (their thoughts, emotions, intentions or desires)—that provided the basis for this leap.

Recursion enabled humans to understand at far greater complexity and to appreciate the connectedness of ideas, events and people. The need to share recursive ideas stimulated our need for recursion in language: to embed structures within structures to generate sentences like “Frank, who has a stall at the market, is a farmer who’s married to my friend Melanie, the woman who introduced us to Bennet just before you met Albert when we were in Newark last week having dinner at the Café Rouge.” Recursion enabled us to connect further with each other, to pass on information, and to become storytellers.

Daniel Everett’s research and work with the Pirahã, a hunter-gatherer tribe of the Brazilian Amazon, provides a good example of culture constraining language. The immediate experience is all-important to the Pirahã: they speak only of what they hear, see or infer. Although they believe in and “see” spirits that can take on the shape of animals or people or of visible, tangible things in the environment, they have no concept of a supreme spirit or god. They do not talk of the distant past so have no creation myth. Unsurprisingly their language has no past or future tense, nor is there recursion in its grammar, although they do express recursion in their stories.

Counting systems and numerical understanding appear to evolve from linguistic recursion. The Pirahã have no discrete numbers, and only three that give some notion of quantity—hói, a “small size or amount,” hoí, a “somewhat larger size or amount,” and baágiso, which can mean either to “cause to come together” or “a bunch.” The Pirahã don’t count, they don’t ask for a specific number of anything, presumably because they have never felt the necessity.

MIT professor of brain and cognitive sciences Edward Gibson and his team concluded that: “all human beings share a variety of core numerical capacities (which is probably shared with many other species as well). But both learning and using the ability to remember exact quantities larger than three or four appears to depend crucially on verbal mechanisms. Thus, languages which contain recursive count lists allow their speakers to transcend the core numerical capacities.”

The Australian Aboriginal people, the Guugu Yimithirr, exclusively use cardinal directions, even in confined situations where we would use body-centered directions. For instance, if they wanted someone to move aside, they might say “move a bit to the south.” If they left something in their house, they might say, “I left it on the northern edge of the western table.” Or they might warn a person to “look out for that big hole just north of your western foot.” As a consequence of their language, they have an extraordinarily well developed internal compass, one we would normally associate only with animals like migratory birds or ants, whose unique physical attributes enable this.

Left, Right, and Future

The language we are born with and the way we write it influences how we perceive time in space. English speakers tend to see the past on the left and the future on the right, whereas the reverse is generally the experience of Arabic and Hebrew speakers.

The structure of our language affects how we remember events. For example, speakers of Spanish and Japanese have a different way of describing an accidental event from events where a deliberate action is involved. If Sally broke the vase by accident, we still say: “Sally broke the vase” whereas they would say “the vase broke itself” or “the vase broke.” Lera Boroditsky, Associate Professor of Cognitive Science at UC San Diego, and her colleagues found that “Spanish and Japanese speakers were less likely to describe the accidents agentively than were English speakers, and they correspondingly remembered who did it less well than English speakers did.”

I like You More in Spanish

Studies of bilingual speakers came up with some startling finds. The way we feel about someone, whether we like or dislike them, depends on the language in which we are asked the question. A study by Oludamini Ogunnaike and his colleagues at Harvard and another by Shai Danziger and his colleagues at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel, looked at Arabic-French bilinguals in Morocco, Spanish-English bilinguals in the U.S. and Arabic-Hebrew bilinguals in Israel. In each case they tested the participants’ implicit biases expressed when speaking each language. Again, according to Boroditsky who reported this: “Surprisingly, the investigators found big shifts in these involuntary, automatic biases in bilinguals depending on the language in which they were tested. The Arabic-Hebrew bilinguals, showed more positive implicit attitudes toward Jews when tested in Hebrew than when tested in Arabic.”

From these and other studies Boroditsky and colleagues confirmed that language can change the way we think and the way we think shapes language. “It is a bidirectional cycle, and actually I think that the fact that these two things can influence each other and can exist in a mutual cycle of influence, allows humans to create complex knowledge so quickly and to be so flexible and so agile in how we think about the world.” She points out that there are about 7,000 languages spoken in the world, each of which encompasses all the ideas, cognitive tools and predispositions of a particular culture, and says: “this great diversity is a real testament to the flexibility and ingenuity of the human mind. It is at the very heart of what makes us human.”

It is our desire to connect with others and with our place in the world, which has been, and remains, the driving force behind humanity’s languages and our most important and vital necessity.

The First Word

The Search for the Origins of Language

Christine Kenneally

Human communication depends on the same genetic foundations as other animals. Some were born with a greater inclination to collaborate, forming the symbolic communication of language.

Numbers and the Making of Us

Counting and the Course of Human Cultures

Caleb Everett

Numbers, says Everett, are a key linguistic innovation that has distinguished our species and reshaped human experience.

Thinking Big

How the Evolution of Social Life Shaped the Human Mind

Robin Dunbar, Clive Gamble & John Gowlett

The social brain that drives our behavior and contemporary culture is essentially the same brain that appeared with the earliest humans some 300,000 years ago.

Social: Why Our Brains are Wired to Connect

Matthew D. Lieberman

Explore the groundbreaking research in social neuroscience revealing that our need to connect with other people is even more fundamental, more basic, than our need for food or shelter. Because of this, our brain uses its spare time to learn about the social world – other people and our relation to them.

The Gap

The Science of What Separates Us from Other Animals

Thomas Suddendorf

A leading research psychologist concludes that our abilities surpass those of animals because our minds evolved two overarching qualities.

In the series: The Evolution of Language

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

Watch: How the Languages We Speak Shape the Ways We Think

UCTVSeminars

Do speakers of different languages think differently? Does learning new languages change the way you think? Do bilinguals think differently when speaking different languages? Does language shape our thinking only when we’re speaking, or does it shape our attentional and cognitive patterns more broadly?

Unlike Humans, Chimpanzees Don’t Enjoy Collaborating

Danielle Venton, Wired

Chimpanzees would prefer to work alone unless a partner can help them get more food. For humans, collaboration is in itself a reward, which is likely a factor in the evolution of our language.