The Great Attention Heist

Recent revelations by IT professionals and social media executives confirm that their products were intentionally designed to “consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible.” As a fundamental human need and capacity, our attention is an invaluable resource for learning and reflection—and at the same time, makes us susceptible to manipulation and control. Understanding how this process works can help us avoid surrendering our minds for the profit of others and the cultural “run to the bottom.”

For years, we have been warned about the addictive and harmful impact of heavy smartphone and internet use, with physicians and brain specialists raising red flags regarding the cognitive price of these technologies. Many of us now recognize that we are addicts, often joking about it in an attempt to lessen the seriousness of this realization. But what had been missing to really drive the fact of digital dependency home was an admission by those who design the technologies that such was their intended goal. This has now changed as a cadre of IT professionals recently broke their silence on the subject, revealing the motivations behind the creation of some of the world’s most popular apps.

Speaking at an event in Philadelphia in November, Sean Parker, the founding president of Facebook, said: “The thought process that went into building these applications, Facebook being the first of them, … was all about: ‘How do we consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible?’” A week earlier, Ramsay Brown, co-founder of Dopamine Labs, a California startup that uses artificial intelligence and neuroscience research to help companies hook people to their apps, told a CBC News reporter: “We’re really living in this new era that we’re not just designing software anymore, we’re designing minds.” To make a profit, he added, companies “need your eyeballs locked in that app as long as humanly possible. And they’re all in a technological arms race to keep you there the longest.”

These revelations confirm what at least one writer has been telling us: that our attention is increasingly treated as a commodity for profit. In his 2016 book The Attention Merchants, recently released in paperback, Tim Wu, a professor of law at Columbia University, shows us how attention, a crucial human function, became the common currency of propagandists, media executives, and internet moguls. The compulsion to prey on eyeballs, Wu argues, long predates our digital gizmos and virtual realms. The advent of mass marketing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries spawned sophisticated advertising techniques geared to arrest and hold the attention of prospective buyers. Eventually, it occurred to American entrepreneurs that information about newspaper readership could be sold to those seeking access to consumers in order to market products. Throughout the 20th century, merchants learned to harvest and barter our attention using ever newer and more efficient media. Attention became one of the hottest commodities on the planet.

Wu tracks the development and use of these technologies from political posters and radio propaganda, to the goldmine of television advertising, to today’s internet and digital media. Today, it is Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, and other “disruptive technologies” that are making billions of dollars reselling attention to advertisers. This attention harvest, as Wu demonstrates, is ubiquitous and ever-evolving, always looking to break new ground. We can see it all around us: advertisements on the backs of taxi seats or in the trays of X-ray machines at the airport; stickers on supermarket produce advertising Disney films; sprawling adverts on the sides of trains, buses, and streetcars. Anywhere our gaze might fall, whether by accident or from necessity, represents a potential locus of attention ambush.

According to Wu, the attention merchant’s basic modus operandi is to engage us with “apparently free stuff” and then resell our attention to others. In this regard, smartphones and tablets—and the applications that support them—represent a quantum leap in the industry’s efforts to win and hold our attention. They are the frontline harvesting machines. So efficient has this process become, and so complete the conquest, that we can say that our awareness is now being commercially farmed. Furthermore, there is no harvest “season” for this industry. It is happening all the time and around the clock: in our homes, on the street, in our workplaces, during vacations. It is a symphony of mental entrancement on a global scale.

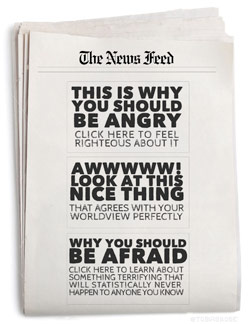

The social effects cannot be underestimated. As Wu writes: “[U]nder competition, the race will naturally run to the bottom. Attention will almost invariably gravitate to the more garish, lurid, outrageous alternative, whatever stimulus may more likely engage what cognitive scientists call our ‘automatic’ attention as opposed to our ‘controlled’ attention, the kind we direct with intent.”

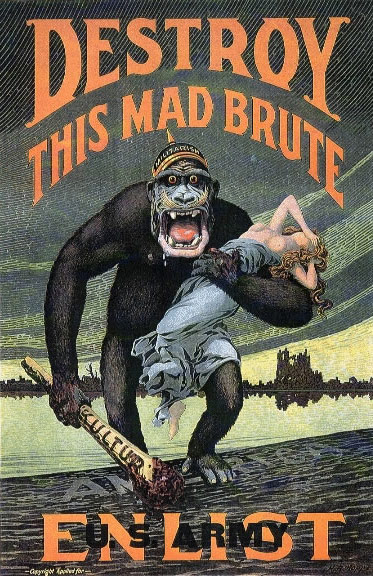

With our unwitting participation, culture devolves into the realm of the crude and stupid. And the story does not end there. Attention capture also has an enormous influence on our politics, being used to marshal peoples and amass power. Wu tells us that, in World War I, the British discovered the power of pervasive propaganda—leaflets, posters, meetings, door-to-door canvassing. George Creel, a journalist who headed President Woodrow Wilson’s public information office during the war, inundated the American people with propaganda. Using more than 75,000 volunteers, he delivered over 775,000 pro-war speeches in movie theaters to an estimated 135 million people, in order to create a popular will to go to war. “In the burgeoning battle for human attention,” Wu writes, “Creel’s approach was the equivalent of carpet-bombing.”

The Nazis took political attention harvesting one step further by adding massive rallies and films to the repertoire. At his war crimes trial, Albert Speer affirmed that “technical devices like the radio and the loudspeaker” had served to deprive “80 million people […] of independent thought. It was thereby possible to subject them to the will of one man.” Today, jihadi groups use every means available to create a will for war, their poetry, videos, and music providing an attractive, full-fledged culture for disaffected youth to become immersed and lost in.

The consequences of this vast gambit for our attention is that we have been drawn into a kind of mental slavery. Masters of profits and propaganda are farming our minds, doing cumulative damage that may go to the very core of our humanity. As a result, our attention is becoming locked into a low level of living and functioning.

Why is attention so important? What is it anyway? And how can we avoid being the willing slaves of the profiteers or political manipulators?

To give and receive attention is a fundamental human need. In the 13th century, King Frederick II of Sicily wanted to find out what language children would naturally grow up to speak if they were never spoken to. He took babies from their mothers at birth and placed them in the care of nurses who were strictly forbidden to either speak to or touch them. The babies, as it turned out, didn’t grow up to speak any language, as they all died of attention deprivation within a fortnight of the start of the experiment. A study involving less extreme methods at the University of British Columbia in 2014 found that the withdrawal of attention—ostracism—is psychologically more harmful than bullying. Negative attention, it seems, is better than no attention at all. By giving and receiving attention, we are meaningfully connected to others and to a larger social whole.

In his 1978 book Learning How to Learn, author and Sufi scholar Idries Shah argued that giving and receiving attention is a cornerstone of human behavior. According to Shah, attention exchange is often the main, underlying motive for any human interaction, regardless of the actors’ overt intention. Yet attention is a brutally limited resource. A healthy attention capacity, involving the ability to block out parts of the world in order to focus, is crucial for learning. We have to be able to properly listen, think about things, and digest and integrate knowledge into a wider context if we are to develop and grow. Attention is the basic currency of this process. Yet we have been giving it away freely to the attention merchants because we do not know that it is precious.

Wu argues that we need a balance between two kinds of attention in order to be healthy: the transitory kind that happens in natural shifts of focus during daily life, and the sustained kind, such as when we are reading a book. But such sustained attention is increasingly ceded to the deliberate and chronic summoning of transitory attention by digital technologists. Instead of a long, uninterrupted read, we are being trained to consume information piecemeal from a medley of screens. This fragmented attention results in fragmented minds, producing people who are unable to focus or think effectively. The outcome is exhaustion through overstimulation of our mind’s neuronal responses, thus weakening our executive faculties and our ability to make coherent and independent decisions.

When our attention is lured, herded, and commandeered in such a way, our full human potential is profoundly subverted. “As William James observed,” Wu writes, “we must reflect that, when when we reach the end of our days, our life experience will equal what we have paid attention to, whether by choice or default.” We become what we attend to—nothing more, nothing less. A steady and exclusive stream of reality TV, entertainment gossip, social media chatter, and “breaking news” about the latest celebrity scandal or Trump’s most recent tweets—all endlessly cycling into each other—turns us into the bland clickbait of the attention harvesters. Yet, though we justifiably consider the enslavement of bodies a terrible wrong, we willingly surrender our minds for the profit of others. This new, almost hip, kind of slavery is sought, not fought.

Like a balanced diet, a healthy capacity for attention enables us to engage and disengage at will, thus freeing us to dwell and reflect. This continual process of focusing, defocusing, and refocusing keeps us aware of larger contexts. And this is how we learn and grow, in some cases attaining greatness in our endeavors or developing a deeper wisdom and outlook on life. “Over the coming century,” Wu writes, “the most vital human resource in need of conservation and protection is likely to be our own consciousness and mental space.” As technologists and entrepreneurs collaborate to bring us the next generation of attention harvesting devices, such as Google Glass and other “smart” wearables, it is imperative that we create spaces and blocks of time that are beyond their reach.

Periodic “unplugging”—taking “digital Sabbaths”—can help us reclaim real (non-virtual) sanctuaries, where we can again interact directly with one another and make strides toward achieving goals that require serious levels of concentration. In cultivating these habits, we also improve our general culture, our shared sense of what is truly meaningful and important. When our attention is diverted toward the crude and sensational, our cultural life suffers. By contrast, a long walk or a good read can lead not only to a healthier and more fulfilling life but also to a richer society, in all senses of that word.

As we would not throw a precious jewel into the trash, so we should not surrender our priceless and finite capacity for attention to the merchants for resale. Attention is infinitely more valuable than we think; it is a crucial tool in the process of learning that life may have more meaning than the officially propagated one.

***

This article was originally published in the LA Review of Books.

The Anxious Generation

How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness

An essential investigation into the collapse of youth mental health—and a plan for a healthier, freer childhood.

By Jonathan Haidt (2024)

The Attention Merchants

The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads

Tim Wu

Columbia law professor Tim Wu explores how our attention, aided by the advent of mass marketing and increasingly sophisticated advertising techniques, has become one of the hottest commodities on the planet and the common currency of propagandists, media executives, and internet moguls.

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power

Shoshana Zuboff

The internet has developed a new form of exploitation, like nothing we’ve seen before. The apt term Shoshanna Zuboff coins for it, “surveillance capitalism” describes a novel paradigm of free enterprise which seeks to convert all human experience into data, and create wealth by predicting, influencing and controlling human behaviour at scale.

In the series: Social Networks

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

This Is How Your Fear and Outrage Are Being Sold for Profit

Tobias Rose-Stockwell, Medium

The story of how one metric has changed the way you see the world.

Facebook Will Now Show You Exactly How It Stalks You — Even When You’re Not Using Facebook

Geoffrey A. Fowler, Washington Post

The new ‘Off-Facebook Activity’ tool reminds us we’re living in a reality TV program where the cameras are always on. Here are the privacy settings to change right now.

‘Our Minds Can Be Hijacked’: The Tech Insiders Who Fear a Smartphone Dystopia

Paul Lewis, The Guardian

Google, Twitter and Facebook workers who helped make technology so addictive are disconnecting themselves from the internet. Meet the Silicon Valley refuseniks alarmed by a race for human attention.