Judaism:

Birth of the Old Testament

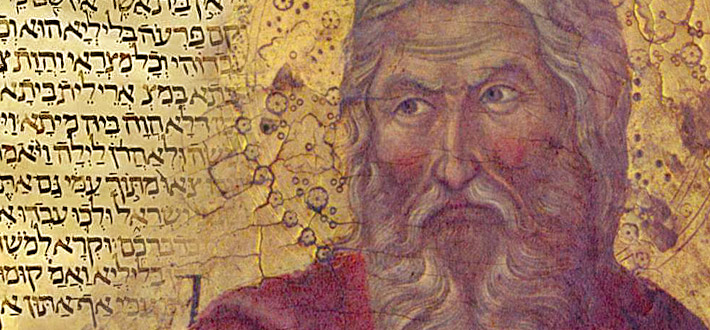

As we’ve noted elsewhere on the site, a pivotal way humanity had communicated throughout our human journey is through stories. As is typical of the ancient world, Jewish oral tradition included myths, memories and ideas absorbed and adapted from the whole region. They would become part of what we know today as the Old Testament.

“There is no nation, no community, without its stories. Children are brought up on fairy tales, cults and religions depend upon them for moral instruction: they are used for entertainment and for training. They are usually catalogued as myths, as humorous tales, as semi-historical fact, and so on, in accordance with what people believe to be their origin and function.

“But what a story can be used for is often what it was originally intended to be used for. The fables of all nations provide a really remarkable example of this, because, if you can understand them at a technical level, they provide the most striking evidence of the persistence of a consistent teaching, preserved sometimes through mere repetition, yet handed down and prized simply because they give a stimulus to the imagination or entertainment for the people at large.” — Idries Shah “The Teaching Story: Observations of the Folklore of our ‘Modern’ Thought”

In 725 BCE, the Israelites were conquered by Shalmaneser of Assyria. Many Jews were taken into exile in Assyria, while foreigners from Babylon, Persia and surrounding areas were brought to Israel to replace them. The writers of the Pentateuch (the “five books” being Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy) began at about this time to weave legends from Babylon, the Persian Empire and other places into biblical accounts of the Creation and the Deluge.

Axial sages (900–200 BCE approx.) sought a cure for the spiritual malaise they experienced around them. Today our creative and intellectual energy focuses on science and technology, while our emotions tend to direct our spiritual quest, if there is one. As a result, our society has made breakthroughs in science and technology, but we are vulnerable to indoctrination rather than spiritual growth. Often we tend to believe and follow what we are told by the conventions of our upbringing. A close look at how our religious traditions evolved will help us understand how we arrived at our contemporary religious beliefs and the rituals that accompany them. This is a fascinating story and one that will help us understand the forces that shape human thought and appreciate our mind’s great potential for change and development.

Many stories repeated throughout human history were originally created to contain deeper levels of meaning that would foster an intuitive perception in those that studied them. As an example, Maimonides (Moses Ben Maimon, 12th Century, Cordoba), one of the most celebrated Rabbis, wrote the following about Genesis in The Guide for the Perplexed:

“We must not understand, or take in a literal sense, what is written in the book on the Creation, nor form of it the same ideas which are participated by the generality of mankind. Otherwise our ancient sages would not have so much recommended to us, to hide the real meaning of it, and not to lift the allegorical veil, which covers the truth contained there. When taken in its literal sense, the work gives the most absurd and most extravagant ideas of the Deity. ‘Whosoever should divine its true meaning ought to take great care in not divulging it.’ This is a maxim repeated to us by all our sages, principally concerning the understanding of the work of the six days.”

Because of their entertainment and social value, the longevity of these stories was assured; they would spread across continents, absorbed and adopted by people ‘as their own’; be modified by enculturation and time. Some became emblematic of different peoples at different points in history.

They were never to be understood as literally true, but as instruments of learning, through which individual communities experienced identity and connectedness; while, at the same time, containing universal understandings of human nature and evolution.

Unsurprisingly then, the Jewish oral tradition in its earliest times included stories absorbed and adapted from the whole region. As early as 725 BCE, the Israelites were conquered by Shalmaneser of Assyria. Many Jews were taken into exile in Assyria, while foreigners from Babylon, Persia and surrounding areas were brought to Israel to replace them. The first of the three writers of the Pentateuch (the “five books” being: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy) began at about this time to weave legends from Babylon, the Persian Empire and other places into biblical accounts of the Creation and the Deluge.

Babylonian Beginnings

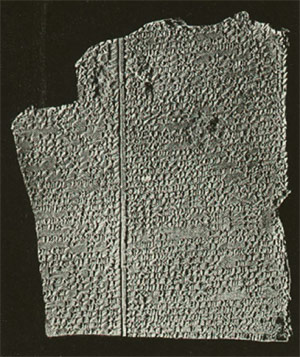

In 669 BCE, Ashurbanipal became ruler of the Assyrian Empire. His library is the largest so far uncovered in Mesopotamia. During his reign he added more to the library at Nineveh than any of his ancestors had done over the previous two centuries.

Much of our knowledge of ancient Babylonian myths and early history comes from his effort. Among the books archeologists have recovered from the palace library were the Babylonian creation myth, spread out over seven tablets, and the Epic of Gilgamesh, spread out over 12 tablets. The tablets survived into modern times because when the nomadic Chaldeans from the southeast and Medes (ancient Persians) destroyed Nineveh in 612 BCE, they were content to push in the palace walls with battering rams, so the walls collapsed, burying and preserving the tablets for the benefit of modern scholars and archeologists.

The Flood story in the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh found on 12 tablets at Nineveh is very close to the biblical one, but it predates the Bible story by at least 2,000 years. The Izdubar (or “Gilgamesh”) legends included not only the Story of the Flood, but the story of the Tower of Babel and of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah as well, all originally written down at least as early as 2000 BCE from an oral tradition that was very much older.

Like Moses, Sargon, the Akkadian king who unified Sumer, was found in a reed basket that was floating up a river and brought up under the protection of the high priestess of Inanna, who was more than likely a royal princess.

The Meeting of Minds: Two Great Empires

The Story of the Flood, the story of the Tower of Babel, and the story of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah were all originally written down at least as early as 2,000 BCE from an oral tradition that was very much older.

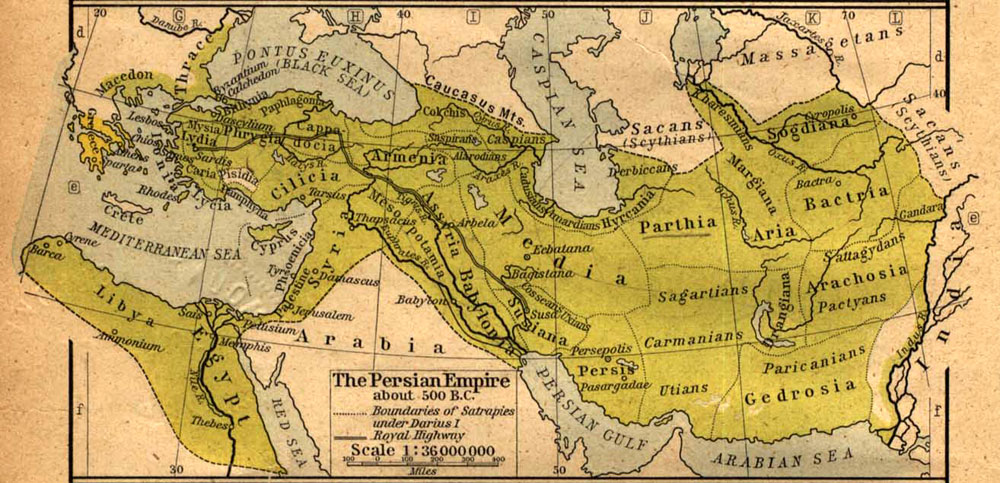

From 668–627 BCE, in the time of Ashurbanipal and the Neo-Babylonian Dynasty and again in the Early Persian period of Cyrus the Great, Marduk was the chief god of Babylon. Because they opposed the oppressive measures of Nabonidus, the last Neo-Babylonian king, the priests of Marduk facilitated the peaceful occupation of Babylon by Cyrus.

With Cyrus and the Persians came the teachings of Zoroaster, which claimed Ahura Mazda as the Supreme True God.

These two ways of understanding the universe and our place in it (the Marduk belief and Zoroastrianism) would influence Judeo-Christian thought from its first recorded beginnings to the present day.

In 612 BCE, these ancient Persians, known as Medians, joined with the Babylonians to defeat the Assyrian Empire. As a consequence, both established their respective authority in the region for about sixty years.

Keep in mind that these early empires were concerned with expanding power and prosperity, not with retaining their own religious thought as opposed to anyone else’s.

“… the ancient religions including Judaism prior to Ezra and Nehemiah were not dogmatic and intolerant to other beliefs. In the ancient Near Eastern religions there is a complete absence of the concept of false faith or of heresy. Nor does there seem to be any notion of racial hatred or any feeling of any form of superiority of one people over another.” (From Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture.)

Ideas about cultural life and religion traveled between the two empires. King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon was married to Amytis of Media, for whom he built the hanging gardens of Babylon. Through such arrangements, these great powers maintained adjacent realms in equilibrium until about 549 BCE, when Cyrus the Great established the Achaemenid Empire (ca 550–330 BCE) by defeating King Astyages of Media.

Babylon, Zoroaster and Greece Influence Jewish Thought

In 597 BCE, this same Nebuchadnezzar, son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, violently ransacked Judah and took the young king Jehoiachin and 8,000 of his people. These were only the most prominent citizens of Judah: professionals, priests, craftsmen, and the wealthy. The “people of the land” (am-hares) were allowed to stay behind.

As Ernst Von Bunsen says in Keys of St. Peter, “It was during the Captivity that idolatry ceased among the Israelites.”

In Babylon, the Jews became fully convinced that Yahweh was the one true God, who could and should be worshipped not through ritual but through their way of life which now focused around personal transformation and responsibility. These changes in thought were Axial and had to have been influenced by exposure to the teachings of the first great Axial sage, Zoroaster.

“Most scholars, Jewish as well as non-Jewish, are of the opinion that Judaism was strongly influenced by Zoroastrianism in views relating to angelology and demonology, and probably also in the doctrine of the resurrection, as well as in eschatological ideas [the part of theology concerned with death, judgment and destiny] in general, and also that the monotheistic conception of Yahweh may have been quickened and strengthened by being opposed to the dualism or quasi-monotheism of the Persians.” (Jewish Encyclopedia)

Both are revealed religions: in the one, Ahura Mazda imparts his revelation and pronounces his commandments to Zarathustra on “the Mountain of the Two Holy Communing Ones”; in the other, Yahweh holds a similar communion with Moses on Mount Sinai.

Both share the doctrines of a regenerate world, a perfect kingdom, the coming of a Messiah, the Resurrection of the Dead, and the Life Everlasting.

The Magian (Magi were Zoroastrian priests) laws of purification, more particularly those practiced to removing pollution incurred through contact with dead or unclean matter, are given in the Vendïdād (the ecclesiastical code within the Avesta) quite as elaborately as in the Levitical code, with which the Zoroastrian Avesta has been compared.

The six days of Creation in Genesis find a parallel in the six periods of Creation described in the Zoroastrian scriptures.

“The notion of Satan as the author of evil appears only in the later books, composed after the Jews had come into close contact with Persian ideas.”

Humankind, according to each religion, is descended from a single couple: the Original Couple. Mashya (man) and Mashyana are the Iranian Adam (man) and Eve. According to the Persian Avesta, the first couple lived originally in purity and innocence, until an evil demon came to them in the form of a serpent, sent by Ahriman, the prince of devils, and gave them the fruit from a tree, which promised immortality. They ate, and as a consequence forfeited eternal happiness and for the first time felt envy, hatred, discord and rebellion.

John Fiske says in Myths and Myth-Makers, “The story of the Serpent in Eden is an Aryan story in every particular. The notion of Satan as the author of evil appears only in the later books, composed after the Jews had come into close contact with Persian ideas.”

In the Bible a deluge destroys all people except Noah, a single righteous individual, and his family; in the Avesta a winter depopulates the earth except in the Vara (“enclosure”) of the blessed Yima. In each case the earth is peopled anew with the best two of every kind and is afterward divided into three realms. The three sons of Yima’s successor Thraetaona, named Erij (Avesta, “Airya”), Selm (Avesta, “Sairima”), and Tur (Avesta, “Tura”), are the inheritors in the Persian account; Shem, Ham, and Japheth, in the Semitic story.

Because of the language in which they were written, Jewish scholars may not have directly read the Zoroastrian scriptures, but they would certainly have come across Zoroastrianism in private dialogues and in political and civic experience. Most of Zoroastrianism known and practiced among people at that time must have been perpetuated through word of mouth. Stories about God, the Creation, the ethical and cosmic conflict of Good and Evil, the divine Judgment and even the end of the world would have been part of this oral tradition.

Jews who were taken captive by the Babylonian and Edomite armies were sold as slaves, some to Greeks who took them to “the Islands of the Sea” where Greek legends became familiar and were absorbed. The idea of an Eden, where everything was originally perfect, can be found in a number of early traditions. In ancient Greece men originally led an idyllic life; they “lived like gods” according to the poet Hesiod. But trouble came in the form of inquisitiveness when Epimetheus received a gift from Zeus in the form of Pandora, a beautiful maiden bearing a lidded vase that should not have been opened. Once it was, everything negative escaped.

Stories and storytelling were pivotal to life in the ancient world. Elements and selected ideas within stories were adopted and adapted as deemed necessary and would again be transformed from their original setting to serve another time and place.

Stories these Jewish scholars collected were reassuringly familiar and still emotionally satisfying when woven by scribes and scholars into a tapestry of myth and historical fact. The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (1 BCE) refers to the story of the expulsion of foreigners from Egypt, and refers to Moses as “a wise and valiant leader” who led the Jews into Palestine. But the writer of the biblical “history” was also evidently quite familiar with the legend of the god Bacchus. Bacchus had two mothers, one by nature and one by adoption; so had Moses. The infant Moses, by the command of the Pharaoh, was put in a basket made of bulrushes and cast into the Nile; the infant Bacchus, by the command of the king of Thebes, was put in a chest and thrown into the Nile. Both Bacchus and Moses have a rod with which to perform miracles; both use it to draw water from a rock; both can transform it into a serpent; both divide waters; both men were called the “Law-giver” and their laws were written on two tablets of stone.

The Jewish Messiah

The Messiah of Jewish prophesy is not the unique Savior he would become for the Christians, but anyone whose service to the Jewish people is deemed great. This idea may well have come from the Gathas. Zarathustra describes a saoshyant (savior) as anyone who is a benefactor of the people.

The word “messiah” means “anointed one,” that is “anointed” by God to fulfill his role. In Second Isaiah or “Deutero-Isaiah” the prophet speaks of a Savior who would come to rescue the Jewish people. In the passage below, he identifies the Persian king Cyrus the Liberator as that Messiah.

Isaiah 44:28 (New International Version)

28 who says of Cyrus, “He is my shepherd

and will accomplish all that I please;

he will say of Jerusalem, ‘Let it be rebuilt,’

and of the temple, ‘Let its foundations be laid.’”

Isaiah 45

1 “This is what the Lord says to his anointed,

to Cyrus, whose right hand I take hold of

to subdue nations before him

and to strip kings of their armor,

to open doors before him

so that gates will not be shut:

2 I will go before you

and will level the mountains;

I will break down gates of bronze

and cut through bars of iron.

3 I will give you the treasures of darkness,

riches stored in secret places,

so that you may know that I am the Lord,

the God of Israel, who summons you by name.

4 For the sake of Jacob my servant,

of Israel my chosen,

I summon you by name

and bestow on you a title of honor,

though you do not acknowledge me.”

Isaiah’s Cyrus might well have been Cyrus the Great or Cyrus I. In either case, a ruler of the Persian Empire, a Zoroastrian, is anointed and honored by Yahweh.

To quote the scholar, Dr. Allen P. Ross, (Univ. Cambridge) Professor of Old Testament and Hebrew at Beeson Divinity School:

“The movements of these world powers were well-known in the various courts, including Jerusalem. And the Book of Isaiah gives sufficient evidence that the prophet knew international affairs. The growth and influence of the Persian Empire was not hidden from the rest of the world; this state and its kings were not non-existent until 536 B.C. And a name ‘Cyrus’ was associated with this rising power as early as 670 – 660 B.C. or thereabouts. This was Cyrus I, the grandson of Cyrus the Great. … The royal line of which Cyrus the Great was a part was founded by Achaemenes, who ruled the Empire from 700-675 (contemporary with Isaiah). His son was Teispes (675-640); he expanded the boundaries of Parsa (Persia) as far south as Pasargadae. Because his empire was so great, he divided it between his two sons, Ariaramnes in the South and Cyrus I in the North. This division meant that there was a ruler known as Cyrus around 70 years before Israel went into captivity.”

It was during their Exile that the Jews learned to hate idol worship and to rely on the word of the one true God. Some scholars see such passages in Isaiah as the first evidence that Yahweh had become a universal God of love: good, perfect, more remote, and identical to Ahura Mazda.

The Resurrection of the Dead and Life Everlasting

Daniel was the first Jewish prophet to refer to the resurrection and to everlasting life: And many of them that sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt (Daniel 12:2 KJV). Given Daniel’s position as advisor to Darius the Great, it seems likely that there was a Zoroastrian influence here.

At least three other sources, scholars suggest, refer to the resurrection and are included here, though an alternative, interpretation seems equally likely:

Let favour be shewed to the wicked, yet will he not learn righteousness: in the land of uprightness will he deal unjustly and will not behold the majesty of the Lord. (Isaiah 26:10 KJV)

Here “behold the majesty of the Lord” is as likely to refer to a state of mystical awareness than it is to resurrection.

I will ransom them from the power of the grave; I will redeem them from death: O death, I will be thy plagues; O grave, I will be thy destruction: repentance shall be hid from mine eyes. (Hosea 13:14 KJV)

Again, this more likely refers to the tradition of many prophets, including Mohammad’s “Die before you die,” that is, one’s lesser self has to “die” in order for the essential self to take control.

The wicked is driven away in his wickedness: but the righteous hath hope in his death. (Proverbs 14:32 KJV)

The same idea as above applies here: the late Sufi philosopher, Idries Shah, refers to the “self” which has to “die” as: “the mixture of primitive emotionality and irrelevant associations which bedevil” undeveloped man. See The Commanding Self by Idries Shah.

In this way, Zoroastrian teachings, Babylonian, Greek and other foreign myths were assimilated into Jewish history and religious culture. Their scholars sought to adjust traditional religious life and thought to a changing world, one that would confirm their status as the chosen people in a covenant with the one true God. Like the Homeric tales, these stories, whose overt purpose was to identify and inspire a people, were originally absorbed by the Jewish people as oral tradition containing fundamental truths about themselves. But, once written down, the Old Testament would be read, centuries later, as Jewish history.