Book Review

Our Dollar, Your Problem

An Insider’s View of Seven Turbulent Decades of Global Finance, and the Road Ahead

By Kenneth Rogoff

Reviewed by Ayubkhon Azamov

The dominance of a global currency is never permanent. History shows that sooner or later, one leader gives way to another. The US dollar is only the latest chapter in this long chain. At the beginning of his book Our Dollar, Your Problem, author Kenneth Rogoff—a former IMF chief economist and Harvard professor—compares the dollar’s trajectory to the fate of earlier world currencies: the Spanish real, the Dutch guilder, and the British pound. Each reigned for centuries, yet all eventually declined under the weight of political, military, and economic upheavals. “The dollar continues this chain, but its era will not last forever,” Rogoff notes.

In the 16th century, Spain became the first true “financial superpower.” A massive inflow of silver from the Americas turned its currency into the world’s standard. But greed and unchecked spending pushed the empire into repeated defaults, including the infamous “triple default” of 1575, when Spain formally declared it couldn’t pay its debts three separate times in a single year. Even with its mighty army and vast global trade networks, Spain was unable to preserve monetary leadership in the long run.

In the 19th century, Britain took up the mantle. Backed by London’s banking system and the vast reach of its colonial markets, the pound sterling secured the country’s dominance in the global economy. Yet after two world wars, the pound lost its strength, and the United States rose to the forefront, armed with the world’s largest gold reserves and unmatched industrial capacity. In 1944, the Bretton Woods system formally enshrined the dollar as the anchor of the international financial order.

As Rogoff writes, “…the world’s dominant currency does not change hands very often—one to two centuries is the norm, and the transition is typically marked by the co-existence of both the old dominant currency and the eventual new champion.” In other words, monetary power changes slowly, not abruptly.

Today, more than 80% of global trade is still denominated in US dollars. The currency serves as a universal “intermediary,” while central banks in emerging economies prefer to hold their reserves in dollars as a shield against currency crises. The United States, meanwhile, enjoys a unique privilege: the ability to finance its debt in its own currency. This asymmetry creates a paradoxical situation: while the world depends on Washington’s decisions, a single move by the Federal Reserve can, to put it mildly, send shockwaves across the globe.

Since the end of World War II, challengers to the dollar have periodically emerged, with many economists predicting that new players might seize the role of monetary hegemon. Yet institutional weaknesses and fragile financial systems have consistently prevented these attempts from succeeding.

Past Currency Contenders to Replace the Dollar

The first serious contender was the Soviet Union in the 1960s and 70s. At the time, economists spoke of “catch-up modernization”—the idea that the USSR could quickly close the gap with richer nations through rapid industrialization and investment. Washington itself treated the USSR as a genuine threat. But the reality was far less impressive: its planned economy was inefficient, innovation stagnated, and the focus on military power created only the illusion of parity. In the end, the ruble never came close to becoming a true alternative to the dollar.

Attention then shifted to Japan in the 1980s, when its export boom, soaring stock and real estate markets, and ambitious banks seemed to signal an imminent rise to global dominance. For a moment, it looked as if Japan might overtake the United States. Yet the Plaza Accord—an agreement that deliberately strengthened the yen—helped trigger asset bubbles, where stock values soared far beyond their real worth, only to collapse. This turned the “Japanese miracle” into the “lost decades,” illustrating that even rapid growth and technological strength cannot guarantee monetary leadership when structural weaknesses run deep.

In the following decade, Europe entered the stage with its bold experiment: the creation of the euro. It quickly established itself as the world’s second most important currency, but it never achieved true global hegemony. Institutional gaps—such as the absence of a unified fiscal system—combined with sluggish growth and heavy social spending limited its reach. Even so, the euro’s credibility, anchored in the independence of the European Central Bank, continues to give it resilience and makes it a plausible “plan B” should confidence in the dollar falter.

Most recently, after the 2008 global financial crisis, China emerged as the most likely challenger. Its combination of tight state control, vast reserves, and a dynamic private sector gave an aura of stability and inevitability. Yet beneath the surface, a shrinking and aging population, rising debt, and an overheating property market revealed deep vulnerabilities. Today, the Chinese yuan is gaining traction in regional trade, but on the global stage it still lacks the essential ingredients for leadership: trust and transparency.

China’s trajectory serves as a reminder that even seemingly unstoppable economies can stumble when structural weaknesses catch up with them. This lesson, however, is not unique to China—it reflects a broader truth about the fragility of global finance.

Fixed Exchange Rate Regimes and Currency Crises

Beyond the vulnerabilities of any single country, another recurring fault line lies in the very architecture of exchange-rate regimes. The history of fixed exchange rates shows how apparent stability often concealed the seeds of future crises. Pegging (fixing a country’s currency) to the dollar provided households and businesses with predictability, made cross-border transactions easier, and reinforced confidence. Yet it also stripped countries of the flexibility they needed, leaving them hostage to volatile capital flows. The “impossible trinity,” described by economist Robert Mundell—that no nation can simultaneously maintain a fixed exchange rate, an independent monetary policy, and free capital movement—has been proven right time and again.

Rogoff reminds us that the experiences of different countries vividly confirm the fragility of fixed exchange-rate regimes. Finland and Sweden could not withstand speculative attacks; Britain suffered a collapse on “Black Wednesday” in 1992; and Argentina and Venezuela used currency pegs as a supposed “anchor of confidence,” but almost invariably ended in crisis. Even the European Exchange Rate Mechanism eventually buckled under pressure.

In Asia, the crises of 1997–1998 became a watershed moment: some countries allowed sharp devaluations of their currencies, others imposed capital controls by restricting the flow of money in and out, and Hong Kong managed to preserve its peg to the dollar only at the cost of enormous foreign reserves. These episodes taught economists that fixed exchange rates can function only temporarily and only when supported by strong institutions; otherwise, they risk becoming a trap.

In response, Asia developed its own approach, later known as the “Tokyo Consensus.” Its essence lay in amassing dollar reserves, adopting flexible exchange-rate bands, and strengthening domestic financial markets. This strategy delivered greater resilience and reduced reliance on the IMF, but it came at the price of channeling vast sums into low-yield US Treasury bonds. Paradoxically, the dollar, long viewed as a source of risk, became the very instrument of protection.

The history of currency crises pushed economists to search for more universal solutions. John Maynard Keynes once proposed the creation of a global currency, known as the “bancor”, and an international clearing system to avoid destructive devaluations. But in the postwar financial order, it was the dollar that prevailed. A modern counterpart to this idea emerged in the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDRs)—a basket of currencies designed as an additional reserve instrument. Yet despite proposals by George Soros, Joseph Stiglitz, and Mark Carney to expand their use, SDRs have remained little more than an accounting unit. In fact, their allocation only underscored global inequality: wealthy nations received the lion’s share, while poorer countries were left with token support. Ultimately, SDRs create the illusion of liquidity but cannot replace the dollar or resolve the structural problems of the world economy.

Cryptocurrencies and Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC)

Rogoff then turns to cryptocurrencies. Bitcoin and its peers have carved out a niche in the unregulated shadow economy, but they are far from being able to replace sovereign money, he tells us. Their value is backed by neither law, nor tax systems, nor banking institutions. The collapse of the FTX exchange made this painfully clear: crypto platforms function essentially as banks without insurance, and once a mass withdrawal begins, a crash is inevitable. A more practical alternative has been the rise of stablecoins pegged to the dollar—but even here, their stability ultimately depends on regulation and trust.

Today yet another topic is increasingly in the spotlight: central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), often described as “digital cash.” China is already actively testing the e-CNY, Europe is debating the launch of a digital euro, while the United States has so far chosen a more cautious approach. The idea carries clear advantages—fast payments, transparency, and user convenience. But it also raises serious concerns: the disruption of the traditional banking system, heightened cybersecurity threats, and the risk of excessive government control.

Unlike cryptocurrencies, which never became (and, as Rogoff stresses, never will become) a true alternative to the dollar, CBDCs appear to hold more potential as a challenge to the existing order because they are issued and backed by governments and can be integrated into the mainstream financial system. For now, however, they function as a complement rather than a replacement. The foundation of global finance remains the same: the dollar and its “exorbitant privilege.”

US Dollar Hegemony: For How Much Longer?

For decades, the United States has reaped the benefits of this privilege—borrowing at low interest rates while investing abroad at far higher returns. Europe, meanwhile, has been content to hold low-yield US Treasuries, while American corporations used those flows to acquire companies and assets across the globe. This asymmetric exchange was made possible by a unique combination of factors: the Bretton Woods system, the Marshall Plan, the preservation of America’s industrial base after the war, and the strength of its institutions. Together, these elements cemented the United States’ position as the “world’s banker.”

Yet dollar hegemony comes at a cost for the United States. On the one hand, it enjoys cheap financing and the status of a global “safe haven” for capital. On the other, it must shoulder enormous military expenditures and insure the world against systemic risks. The dollar and the military are inseparably linked: military power underpins trust in the currency, while the dollar’s privileges make it easier to finance that power. But, as Rogoff warns, “the greatest dangers to the dollar’s supremacy come from within, and it does not matter which party is in power, especially if one or the other has too much of it.”

The dynamics of US debt are increasingly beginning to resemble a “permanent deficit crisis.” An aging population drives ever-higher spending on healthcare and pensions, while cutting defense or social programs is politically next to impossible. Comparisons with Japan are misleading: Tokyo has managed its debt thanks to domestic savings, but at the price of decades of economic stagnation. For the United States, such a model would be even riskier.

“If rapidly rising debt is left unchecked, and there seems to be little political appetite to rein in massive deficits, the United States and the world are in for a sustained period of global financial volatility marked by higher average real interest rates and inflation and more frequent bouts of debt and financial crises,” Rogoff writes.

End Times

Elites, Counter Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration

By Peter Turchin

Review by John Zada, Contributing Writer

In End Times, Peter Turchin examines the complex interplay of socio-economic factors that, he asserts, repeatedly throw societies into decay, crisis, and often violent collapse.

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Thomas Piketty

A leading economist documents the trend of income inequality through history, stressing that the way an economy functions is directly related to a power structure that is determined and maintained by the few who hold the wealth.

Doughnut Economics

7 Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist

Kate Raworth; reviewed by George Kasabov

A “renegade economist” advances a new, more comprehensive and regenerative economic model – one based on a view of humans as socially adaptable beings in a world of limited natural resources.

The Business of Changing the World

How Billionaires, Tech Disrupters, and Social Entrepreneurs Are Transforming the Global Aid Industry

Raj Kumar

In 2000, Raj Kumar and friends created Devex, an online community for global development that matches up organizations with funding opportunities. This book was written 20 years later to provide a clearer picture of how the aid industry operates, and where it’s headed.

Creating a Learning Society

A New Approach to Growth, Development, and Social Progress

Joseph E. Stiglitz

A Nobel economist and a leading finance expert posit the view that learning is more important to growth and development than the accumulation of capital.

In the series: The Changing World Economy

- Trust, Faith and Confidence–Value and the Role of Money

- Risk, Gambling, and Financialization

- Aid: Ending Global Poverty

- Forgiveness of Debt and the Creation of Money

- End Times: Elites, Counter Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration

- Capital in the Twenty First Century

- Doughnut Economics

- The Business of Changing the World

- Creating a Learning Society

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

The Twilight of America’s Financial Empire?

WTFinance podcast

The conversation covers liberation day, impact on global economy, whether it would help manufacturing in the US, deficits, risk of US Dollar supremacy and more.

New Thoughts on Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Thomas Piketty, TED

French economist Thomas Piketty caused a sensation in early 2014 with his book on a simple, brutal formula explaining economic inequality: r > g (meaning that return on capital is generally higher than economic growth). Here, he talks through the massive data set that led him to conclude: Economic inequality is not new, but it is getting worse, with radical possible impacts.

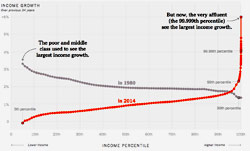

Our Broken Economy, in One Simple Chart

David Leonhard, New York Times

Three leading economists provide a dramatic look at the skyrocketing income growth of the 0.01% very rich vs. all other Americans over the past 34 years.