The World of the Poor

The poor live with lawlessness, poor nutrition, low quality of education, and have so little cash reserves that simple mistakes or health problems can have devastating consequences.

The best solutions involve breaking down utopian goals and addressing smaller everyday problems with innovative, empowering solutions at a grassroots level.

“The rule of law enables citizens to invest in their own futures and exercise their rights. It enables governments to govern better, respond to emerging challenges, and advance human development”

Helen Clark, UN Development Program, 2012

Everyday Violence and Absence of the Rule of Law

According to the UN most poor people don’t live under the shelter of the law, but far from the law’s protection. In their book The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence, the International Justice Mission’s Gary Haugen and co-author Victor Boutros state correctly that “When we think of global poverty we readily think of hunger, disease, homelessness, illiteracy, dirty water, and a lack of education, but very few of us immediately think of the global poor’s chronic vulnerability to violence – the massive epidemic of sexual violence, forced labor, illegal detention, land theft, assault, police abuse, and oppression that lies hidden underneath the more visible deprivations of the poor.”

Lawlessness has unleashed gender-based violence which now represents a greater risk of death and physical harm than cancer, motor accidents, war and malaria combined.

Everyday violence in rural areas and inner cities of the developing world rarely makes the headlines. According to Haugen, lawlessness has unleashed gender-based violence which now represents a greater risk of death and physical harm than cancer, motor accidents, war and malaria combined. If you sexually assault a child in Bolivia, he says, you are at greater risk of slipping in the shower than of going to jail, and in India a rapist has a greater chance of being struck by lightning than being charged for his crime. By hiring private security services, people in power have figured out how to stay safe and succeed without a public justice system, so they have little interest in changing the status quo.

When trying to imagine the life of the poor, we need to remember that the vast majority, particularly of women and children, live in relentless, unremitting fear of extortion and violence every single day of their lives.

There are an estimated 50 million men, women and children, held in slavery in the world today, and more in India than in any other country in the world. They toil in factories, farms, plantations and private homes. The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that there are some 3.3 million children in slavery or forced labor. They are deprived of an education, forced to work day and night, and frequently subjected to violent abuse and sexual assault. “By every conceivable measure, the victims of modern-day slavery tend to be the poorest people—and low-income countries tend to have the highest levels of slavery.”

As Jacquelline Fuller, former Director of Google.org says, “unchecked violent crime against the poorest, especially girls and women, isn’t just a human rights problem. It is a drag on development that no amount of foreign aid can fix if functioning public justice systems aren’t part of the solution.”

Malnutrition and the Lack of Health Care

The usual definition of a poor person is someone who doesn’t have enough to eat. However, thanks to increased food production, reduced physical labor and improvements in water and sanitation, most people in poor communities do eat enough and only the very poor would benefit greatly from increased food consumption. The problem is not the quantity but the quality of the food. The poor suffer from a lack of micronutrients in their diet, which can make a person weak and unable to work. Indeed, anemia is a major health problem in many parts of Africa and Asia. Of course, supplements can easily change this: in rural Indonesia men who were given iron-fortified fish sauce were able to work harder and earned more money as a consequence.

The poor lack information, so they may not understand the value of eating better. Families could spend more on food if they stopped spending money on alcohol, tobacco, and festivals; but even when they do spend more on food, they prefer to buy better tasting food, rather than food that is more nutritious, like coarse grains and leafy vegetables. Since they’re often suspicious of advice from outsiders, local people must be trained to educate their communities’ members about good nutrition and its advantages. On one occasion, people protested when the chief minister of West Bengal suggested they eat more vegetables and less rice to save money and improve their health.

Height is a measure of good nutrition during childhood and poor people in South Asia are quite small. In 2019, roughly 14.5% of the population in India was undernourished. Malnutrition in childhood can impair a person’s developmental capacity and his subsequent ability to earn money as an adult. A small investment in childhood nutrition can have a big payoff in future health and earning potential: simple steps like providing children and pregnant mothers with fortified foods that are rich in vital nutrients. For example, in Colombia nutritional packets are sprinkled on children’s meals, and in Tanzania mothers are given iodine during pregnancy.

A small investment in childhood nutrition can have a big payoff in future health and earning potential.

Poor people care about health and spend a considerable amount of money on health care, but the quality of health care available to the poor is generally low. The majority of doctors tend to under-diagnose and over-medicate. The misuse of antibiotics along with poor patient compliance is causing a rise in antibiotic resistance. Government health providers make it difficult for people to receive care, since clinics are often closed and health workers are frequently absent from work. Doctors spend very little time with their patients who are then forced to rely on self-diagnosis.

People can only make decisions about healthcare based on their beliefs and understanding, but many poor people don’t have a basic understanding of biology and little reason to trust doctors. Many believe that injections are more effective than taking pills, and that doing something is better than doing nothing. Although many ailments go away on their own, too frequently doctors gladly give their patients injections of antibiotics, because the patient feels better and assumes the treatment has worked. If the doctor did nothing people might think he or she was a quack and never go back.

In many instances immunization rates are less than 5%, not only because it’s hard for people to understand the link between the treatment and the absence of disease, but also because mothers get tired of walking all the way to the clinic with their child, only to find the nurse is not there.

As women are becoming more educated, international health inequalities are beginning to narrow and child mortality is falling. Additionally, many women today are working outside the home, and having fewer, healthier children. But enormous problems still remain. Life expectancy in poor countries has increased more slowly than in rich countries, and too many children still die from preventable diseases. Many poor people lack clean water and sanitation, suffer from poor diets, and lack access to quality health care. Though progress has been made, according to the 2019 UNICEF report on child mortality, there are still six countries where 10% of children die before their 5th birthday. Too often countries spend very little on health care: Sub-Saharan Africa spends about $100 per person, compared to $3,866 in Britain and $11,172 in the United States.

See also Global Health.

Child Marriage

According to a 2023 report by UNICEF, one in five girls alive today was married as a child. In 2022, an estimated 12 million girls became child brides. While these unions are recognized as traditional, there is a correlation between the violence and threat of sexual abuse that surrounds the poor and childhood marriage. Parents believe that marriage “protects” girls from sexual assault and harassment and often there seems to be no option but to marry off a girl that one cannot afford to feed.

Larger dowries are not required for young girls, and economically, women’s earnings are insignificant as compared to men’s. The detrimental effects of early marriage on a girl cannot be overstated. Most young brides drop out of school. Pregnant girls from 15-20 are twice as likely to die in childbirth than those 20 or older, while girls under 15 are at five times the risk. Research cites spousal age difference as a significant risk factor for violence and sexual abuse.

Education

In many developing countries, school enrollment has gone up because governments have built more schools and primary education is free. Even secondary school enrollment has gone up, despite the fact that it is more expensive and teenagers could be out earning money for their family. However, the quality of education is low. Teachers on average miss one day of work per week, and even when they do show up they are found drinking tea, reading the newspaper, or talking with colleagues when they should be in the classroom teaching. As a result, many older children cannot read a simple paragraph or solve math problems beyond simple arithmetic.

Parents see education as a way for their children to earn more money, so they tend to invest in the education of the child with the most promise, instead of investing equally in all of their children. They also seem to value secondary school more than primary school, even though each year of schooling increases earnings. Poor children are not encouraged to stay in school unless they are gifted, and teachers only prepare the best students for graduation exams, and ignore those they see as less capable. Many very talented children are not given a chance. But they blame themselves when they fall behind, and eventually drop out and become day laborers or shopkeepers. (See also Education in the Developing World.)

Sources of Income

A person with a steady job can hope and plan for the future, so most poor people around the world seek financial stability and look to regular employment to provide that. With regular employment, it is easier and cheaper to borrow money, children can get into better schools, and hospitals are more willing to perform expensive treatments should these become necessary.

But the majority of poor people don’t have regular employment; instead they work as casual laborers or perhaps run small farms or businesses. Risk is a central part of their everyday lives: one bad decision or unfortunate event can be devastating. Because the land they farm isn’t irrigated, they are extremely vulnerable to drought or delay in the rains, which too often means the loss of all or most of their crops. Casual laborers, unlike regular workers, are usually hired only for a few days or weeks; whether they work or not depends on fluctuations in food prices and on whether the harvest was good or bad.

[Poor] couples often decide to have many children to increase their chances of being provided for in their old age.

When the poor have a drop in income, they have to cut back on essentials, even food. In hard times, those who farm or are business owners are obliged to use their savings, if they have any, or have to borrow money to keep going. But often that’s not enough to make their business profitable, so over time they become poorer and poorer. Some are forced to take drastic steps; others must rely on the charity of relatives. Constant worry leads to stress and depression and an inability to focus, so people become less productive, less able to make rational decisions and more likely to make impulsive ones. With no easy way out, many lose hope and cannot find the strength to start over.

The poor manage risk in many different ways, with most having more than one occupation. Couples often decide to have many children to increase their chances of being provided for in their old age; and some members of a household might have to go to the city to find work that is more lucrative, while others remain in the village. Farmers rely on traditional methods, even though they may be less profitable, because they don’t want to take what they perceive as unnecessary chances. They might choose to replant seeds from last year’s crop because it’s less expensive than buying new seed, which is likely to be more productive.

Forming larger family liaisons through marriage is a traditional way to ensure help during tough times: daughters marry someone in a nearby village, so that both families can rely on each other in times of trouble. There is often a network of borrowing and lending which lowers each individual’s level of risk, although it doesn’t eliminate it. In adverse times, such as severe ill health, villagers help each other by making small loans. The cost of health care is generally so expensive that a family can’t bear the cost alone, and if villagers can’t help, many have to borrow at exorbitant rates from moneylenders to pay for doctors and medicine.

It’s easier for us all to spend money today on what we want than to plan for the future. For the poor, saving is even more difficult. Since having money available for anything but necessities is so rare, whenever they do have any spare it’s tempting to spend it on treats like tea, snacks, alcohol, and tobacco. To counteract this, many poor people “freeze” their money when they can in things like fertilizer or bricks. When a family gets hold of any cash, they buy as many bricks as they can afford to add on to their house, but it’s rarely enough for an entire room. As a consequence, there are many unfinished houses in developing countries.

Although the poor would benefit greatly from saving money, very few have a savings account; instead, they find other ways to save money. Some borrow money in order to save and arrange for the funds to be immediately put in a savings account. By making payments on the loan they impose a discipline on themselves, which otherwise might be lacking. They might deposit money with a local moneylender, or join a savings club like a Rotating Savings and Credit Association (ROSCA). Described as a “poor man’s bank,” ROSCAs don’t charge fees and allow members to make small but equal deposits and pool their money, with each member taking the whole sum once.

In Kenya, M-Pesa (M for mobile, pesa is Swahili for money) is a successful mobile-phone based money transfer and micro-financing service, which was started in 2007. It allows users to deposit, withdraw, and transfer money and to pay for goods and services, and has now expanded to Afghanistan, South Africa, India and Eastern Europe.

Most poor people operate tiny businesses that don’t make much money, have no employees and tend to last no more than three to five years. The median business in Hyderabad India generates about $2 per day. A typical shop has very little inventory and few customers, and several shops in the same village carry similar items. Once women are married, their priority is the home where they are needed to take care of the children and run the household. Nevertheless, women run most of these small businesses, and do so not because they want to, but because it’s necessary for the survival of their families.

Moneylenders charge so much in interest that borrowers barely make enough money to survive.

People in extreme poverty lack the means to improve their economic situation. If a woman realizes that her business will remain small and minimally profitable, her enthusiasm and commitment wanes and she’s likely to spend more time on other things. Lacking cash and denied credit from local banks, the poor must rely on moneylenders to buy raw materials in order to sell their finished products. But moneylenders charge so much in interest that borrowers barely make enough money to survive. This practice is so common in Third World countries that it has become socially acceptable.

If the very poor could borrow money at a reasonable interest rate, they could sell their products on the open market and make enough money to live a decent life. But banks won’t lend money to the poor for a variety of reasons: the loans are too small to be considered worthwhile; the poor have no collateral; they are illiterate and unable to fill out loan forms. Banks will only loan to the poor if a well-to-do person guarantees the loan, although, ironically, the poor are better at paying back loans than people with collateral. The percentage of bad debt from loans to the poor is less than 1%, probably because the indigent know that this may be their chance to break out of the cycle of poverty they are in, and that if they fail, they won’t get a second chance.

Effect of Low Expectation

The poor are under considerable stress and are more susceptible to impulsive decisions, plus saving isn’t attractive when the goals are so remote. Weekly or monthly savings require facing self-control problems repeatedly. Optimism and hope in the future would make it easier to be disciplined enough to save for long-term goals, but too often the poor have low or no expectation of their situation improving.

Because they lack hope in long-term change they prefer to focus on short-term pleasures, which are carefully thought out and reflect strong societal and individual inclinations. In parts of India the extreme poor spend 14% of their budget on festivals, and a mother may start saving money for her daughter’s wedding ten years in advance. This means that while many parents are unwilling to spend a few cents for deworming their children, they will spend a considerable amount of their income on weddings, dowries, christenings and funerals; villagers will spend money to buy a television even though they do not have enough food to eat.

What Approaches Work and When?

Understanding Poverty at the Local Level

Randomized controled trials empower donors and governments to base policy decisions on rigorous evidence, dramatically boosting the impact of aid. In recent years, the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) has scaled its efforts significantly, conducting nearly 1,000 trials across more than 50 countries. The extensive evidence emerging from these studies now offers a detailed, nuanced understanding of the challenges facing the poor, as well as insights into the most effective interventions to alleviate poverty.

Often these are straightforward solutions to everyday problems of communication and convenience, understood by people on the ground. For example, PAL found that water quality improved when free chlorine dispensers were placed within easy reach of community water sources; that students stayed in school longer when parents were given information on the higher wages earned by graduates; and that teachers were more motivated when students were offered merit scholarships.

“When we have the money, they don’t have fertilizer. When they have fertilizer, we don’t have money.”

Fertilizer was underused in much of Africa, which didn’t make sense. So researchers investigated and found that many farmers don’t use fertilizer, even though they know it would improve their harvest, because they can’t save the money they earn from a harvest long enough to be able to spend it on fertilizer when it’s needed for planting. Fertilizer shops often don’t have fertilizer after the harvest when farmers have money to buy it, and it is inconvenient for farmers to keep coming into town to see if there’s fertilizer in stock. When there is money in the house, things always come up and the money disappears; and if there’s no money available, urgent matters are re-evaluated and alternatives found. As noted in their book Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty, Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo noted that a farmer put it exactly: “When we have the money, they don’t have fertilizer. When they have fertilizer, we don’t have money.” Once an innovative program called The Savings and Fertilizer Initiative was set up offering farmers an opportunity to buy fertilizer vouchers right after the harvest, the number of farmers using fertilizer increased by 50%. One study showed that it increased farmer’s net income by more than 50%.

The views of most experts on poverty and development fall into two main categories. There are those, who, like Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University, believe that some countries are in a “poverty trap”—in other words, that the poor cannot get out of poverty because there are not enough chances for advancement—and as a consequence they need a “big push” to get out.

Sachs argues that if public investment and foreign aid are large enough, they will boost household incomes, spurring savings and boosting local investment and encourage external investment by improving infrastructure. In 2006 he initiated the “millennium village project,” choosing 14 places in rural Africa with about 500,000 people and made them the subjects of a $150m project run by Columbia University and African governments.

According to a 2011 article in The Economist, “If the aim of the project is to boost income, investment and economic diversification, it is not clear that these goals are being achieved. For $60 per person per year (which increases the income of the poorest villagers by well over 25%) the project has improved village life only a little more than it would have improved anyway. … So far, the project provides little evidence that ‘big push’ development—advancing on all fronts, flags flying—is better than the alternative: gradual, step-by-step changes to remove specific barriers to growth.”

Economist Bernadette Wanjala of Tilburg University in the Netherlands raised further doubts about the project. She interviewed 236 randomly selected households in Sauri who had been offered the benefits and 175 randomly selected ones who had not. In a study with Roldan Muradian of Radboud University, she concluded “the first group had raised their agricultural productivity by an impressive 70%. Yet she found that the impact on household income was ‘insignificant’, and that there had been little extra saving or investment. The villagers had grown more food—and eaten it. They became better nourished, which was positive, but this did not affect the wider economy.”

Large investments of foreign aid tend to harm governance by increasing the size of the government sector, which increases corruption.

The negatives resulting from large aid investments, as NYU economist William Easterly and others have noted, often appear to outweigh the positives. Large investments of foreign aid tend to harm governance by increasing the size of the government sector, which increases corruption. For example, large sums are expended on fraudulent procurement and graft falsely identified as “development expenditures.” These large amounts also encourage a level of aid dependence that has a retarding effect on growth and development, since there is no perceived pressure to reform while money is flowing in.

“…support for democratic institutions and economic freedom as determinants of growth….”

Without testing the poverty trap theory on a case-by-case basis it’s not possible to really know the situation, although according to Easterly in a working paper published by the Center for Global Development as early as 2005:

“the description of poverty traps, Big Pushes, and takeoffs as a justification for foreign aid receives scarce support in the actual experiences of economic development. The paper instead finds support for democratic institutions and economic freedom as determinants of growth that explain the occasions under which poor countries grow more slowly than rich countries. … development happens when many agents have the institutional environment that allows and motivates them to take small steps from the bottom, as opposed to development happening from a Big Push planner at the top…”

Once a problem is understood, and, as Easterly suggests, if all parties are engaged from the bottom up, holistic approaches can be successful. By 2012 Malawi had suffered from four years of drought, but not everyone suffered thanks to an effort by a Catholic Relief Services Consortium and USAID. They worked with about 20% of the population in eight of the drought-prone districts, offering “a comprehensive program that integrated a variety of activities to address food insecurity: conservation agriculture, treadle pump and gravity-fed irrigation, alternative drought-resistant crops, reforestation, watershed revitalization, fish farming, nutrition, HIV/AIDS prevention and care, sanitation, fuel saving stoves, and village savings and loans.” Farmers planted different crops like chilies, which can survive with less water and are worth five times more than corn. In the 2011 marketing season, farmers in the program sold, as a group, pigeon peas, birds’ eye peas, chilies, rice, sesame and cow peas for more than 34 million Malawi Kwacha—the equivalent of almost $129,000. And the positive results had a ripple effect—neighbors copied these farming practices on their own land. Innovations like these can help end famine and reduce the need for emergency aid. Farmers were able to expand and innovate: they were able to set up fish farms and create village savings and loans associations enabling families for the first time to buy essentials like food, medicine and clothing.

Once a problem is understood … if all parties are engaged from the bottom up, holistic approaches can be successful.

The Economist reported on a seven-year, six-country study of more than 10,000 households which provided assets like cows, goats or chickens to the very poor and training on how to look after them. They also gave temporary income to support the families involved to help them resist the inevitable temptation to eat their potential source of income. This model, which included visits from program workers to reinforce the training and bolster confidence, was followed by local NGOs in Ethiopia, Ghana, Honduras, India, Pakistan and Peru. The NGOs also provided a safe way for participants to save money.

The results were promising. At the end of the programs, roughly two years after participants first enrolled, their monthly consumption of food had risen by around 5% relative to a control group. Household income had also risen, and fewer people reported going to bed hungry than in control households. The value of participants’ assets had increased by 15%, which suggests that they had not improved their diets by eating their chickens, etc. Rather, each person in the program spent an average of 17.5 more minutes a day working, mostly tending to livestock—10% more than their peers. (The impact did still vary by country, being weakest in Honduras and Peru and strongest in Ethiopia.) Even more striking, the program had strong, lasting effects on consumption and asset values even for the poorest tenth of households it reached—the poorest of the poor.

Perhaps most important, when the researchers went back and surveyed households a year after the program had ended, they found that people were still working, earning and eating more. Were these gains to persist an additional year, the researchers estimate that the program would have benefits of between 1.33 and 4.33 times what was spent on it. (The only exception is Honduras, where it did not break even, in part because the chickens that many people chose to receive kept dying.)

Many aid policies have failed not because of corruption or bad intentions, but of ignorance.

Many aid policies have failed not because of corruption or bad intentions, but of ignorance, where the model employed was inaccurately conceived, or the implementation strategy used didn’t work in the specific community. Careful evaluations of relatively modest interventions are helping researchers find what works and identify many cost-effective programs which improve people’s lives, such as deworming, dietary supplements, and vaccinations. Knowledge of local conditions, experimentation, independent evaluation, accountability, and feedback are key to finding the appropriate solutions, since every community has specific needs and priorities which aid organizations need to address. A good example is PROGRESA in Mexico: it pays mothers to keep their children in school and take them to health clinics for check-ups and nutritional supplements. The program both reduces illness and increases school enrollment; children are better able to concentrate and more eager to learn knowing their mothers’ benefits depend upon their staying in school. Once the success of this program became apparent, it spread to other parts of Mexico. Researchers in Kenya found that attendance was 25% higher when preschools provided free breakfast; another rather obvious study showed that students did better on tests once they were provided with textbooks.

Some programs are replicable while others are not, and even with those that are, the local environment dictates how.

Intestinal worms infect 2 billion people worldwide causing anemia and listlessness, and children are especially at risk. In Kenya, when International Child Support asked the parents to pay a few cents for deworming their children, almost all of them refused. The Kenyan government now has a program for deworming all children ages 2–14 who attend school. Investment in deworming programs is not expensive and in some cases is the only way that children will get the treatment they need.

Sleeping under insecticide-treated bed nets can halve the number of people who get infected with malaria, which caused one million deaths in 2008. At that time, one fourth of the children who died in Africa did so because of malaria, so providing these nets universally seemed obvious. Nevertheless, the implementation of the effort had to be studied in comparable groups to find the most effective delivery solution for each situation. For example, it was generally believed that people are always more likely to use something they have paid for and that if things are too cheap, they are not valued. But several studies show that people do use things they get for free. In one study comparing people who purchased subsidized bed nets and those who got them for free, between 60 and 70% used them in both situations. Another study in Kenya found demand was low until the cost was brought down substantially, and highest when clinics offered them for free. Another found that the percentage of people willing to buy a bed net increased only slightly as income rose.

Is Democracy a Factor?

Occasionally, good policies come from the most unlikely sources. Suharto was undoubtedly a corrupt dictator, but he used education to deliver his message and unify Indonesia. Dani Rodrik at the Institute for Advanced Study describes investing in autocracy as “like a very risky bet: you can win big with Lee Kuan Yew, or you could lose it all with Mobutu.” Nevertheless, as we have seen, both multilateral and bilateral aid agencies repeatedly invest in projects where corruption by autocratic governments is persistently rampant and visible.

Mobutu Sese Seko, president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, ruled for 31 years. Mobutu changed the country’s name to Zaire in 1971. Known for his trademark leopard-skin hat, he plundered and looted his way to an estimated $5 billion, with homes in Switzerland and France.

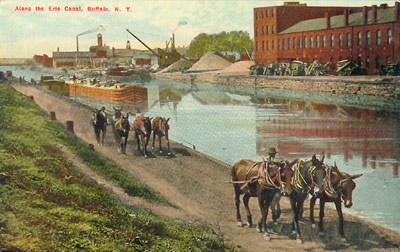

Democracies favor development because they protect individuals by limiting the power of government, the stability of which encourages individual investors and innovators responsive to local conditions. We’ve seen this in American development. When President Thomas Jefferson declined to support the use of federal funds for a canal in New York and his successor James Madison vetoed a bill that would have provided federal money for canal and road projects, an individual named Dewitt Clinton—who would later become New York’s governor—garnered state support for the construction of the Erie Canal. It was completed in 1825 and gave merchants in New York access to markets in the American interior as well as international markets. Because of it, New York became a major international shipping hub, whose flourishing trade created a boom in financial markets and an increase in real estate prices.

A free society provides incentives for individuals to solve their own problems.

So a free society provides incentives for individuals to solve their own problems. Poor health was still a problem in New York in 1850, where one third of all children died before the age of five. Solving this infant mortality crisis came from the efforts of many different groups. First, the causes of death and disease had to be understood, then improvements were made to drinking water and sanitation. Sanitary conditions were difficult to maintain for people living in cramped apartments, so people demanded government action. The Board of Health began enforcing sanitation codes and public-health nurses started teaching mothers the importance of hygiene. The combination of all these efforts led to a dramatic drop in infant mortality by 1920.

A 2004 report in The Journal of Humanitarian Assistance concluded that: “the presence or absence of political and civil rights in the recipient country has one of the greatest effects on the efficiency with which aid promotes development.”

Multilateral and bilateral aid to governments have a much greater chance where there are democracies in place, because once people have a voice and a way to hold elected officials accountable, they force governments to make concessions and become more effective in delivering the services they need.

“The presence or absence of political and civil rights in the recipient country has one of the greatest effects on the efficiency with which aid promotes development.”

Sometimes greater transparency, improvements in accountability and reduction in corruption can take place at the local level, even within authoritarian governments. In 2010, Uganda ranked 127th out of 178 countries in terms of corruption according to Transparency International. The government funds schools but at that time only 13% of the amount reached them, until word got out that district officials were diverting most of the money. Newspapers across the country informed the public. A few years later, when another survey was taken, schools were receiving 80% of the money allocated to them.

The threat of audits reduced theft by community leaders in Indonesia by one-third. Holding local elections can encourage leaders to pay more attention to people’s needs, provided they are free and fair and the elite members of the community don’t dominate the process and discourage others. Again in Indonesia, turnout at Town Hall meetings increased and more villagers spoke out when they received a formal invitation in the mail and knew they were expected to be there to voice their opinions; and they filled out more comment forms when local schools distributed them rather than village leaders.

Generally speaking, voters in developing countries know very little about their candidates and assume they are all equally corrupt, so people vote based on ethnicity rather than merit. When Brazil started to provide voters with useful information by auditing candidates before an election, people were much more likely to vote out corrupt candidates and re-elect honest ones. By converting to electronic voting machines, they enabled many poor illiterate people to vote and they naturally tended to vote for poor, less-educated candidates who favored policies that helped them.

Even when international aid organizations do attempt to offer assistance to autocratic governments on a conditional basis, according to Owen Barder, formerly of the Center for Global Development, it doesn’t work. A change in the hearts and minds of those in power is unlikely to happen unless leaders see advantages for themselves. Pressure and persuasion can, however, work on a government-to-government basis. In 2006 under the government of President Óscar Berger the UN and Guatemala signed the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (in Spanish “Cicig”). It was established to help expose the ties between criminal networks and politicians. When the Northern Triangle countries, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras were seeking $20 billion in US aid, as part of the “Alliance for Prosperity,” the lure of that aid was used by the US to pressure Guatemala’s then President Otto Perez Molina to rid his administration of corrupt officials and to renew the mandate of Cicig.

Cicig emboldened the nation’s own prosecutors to hold the elite to account and became a source of inspiration for many Guatemalans. It encouraged Guatemala City’s middle class, long reluctant to speak out, to join forces with peasant and indigenous groups, in protests and street demonstrations. Eventually, the nation’s church and business leaders also took the side of the protesters to demand change. From April 2015 until the beginning of September, thanks in part to Facebook and other social media outlets, demonstrations grew to include tens of thousands of citizens demanding that their President Otto Perez Molina step down over accusations that he played a major role in a multimillion-dollar fraud scheme. As a consequence Molina was stripped of his immunity from prosecution by a unanimous congressional decision, and was finally jailed on September 3, 2015.

Entrepreneurs

By connecting to local entrepreneurs, large companies can provide a system that treats the poor fairly and enables them to earn more from their labor.

Successful entrepreneurs not only bring new products to market, they can create businesses that hire local people. They pay taxes which can enable local, state and federal governments to provide basic services. They also create demand for products and services which creates additional businesses and jobs to stimulate the market further.

By connecting to local entrepreneurs, large companies can provide a system that treats the poor fairly and enables them to earn more from their labor. When the Indian conglomerate ITC wanted to establish a reliable source of soybeans from subsistence farmers in India, it put personal computers in villages to give farmers the ability to check prices before taking their products to market. It also provided accurate weighing, and immediate payment, and eliminated transportation costs with the result that both ITC and the farmers have benefitted. Called e-Choupals, the ITC initiative trains a farmer to manage the Internet kiosk and become the official e-Choupal Sanchalak (director) for the area. By 2008, 40,000 villages and 4 million farmers had this service, at the time making it the world’s largest rural digital infrastructure created by a private enterprise. The company uses satellites and solar panels to sidestep the state’s shaky power supply and lack of phone lines and is able to offer a full Internet service on these computers to instantly broaden villagers’ horizons.

The best problem solvers are those who deliver what is needed at the highest quality and for the lowest price.

The access to e-Choupals, within walking distance from the farm gate, is supplemented through physical infrastructure—the ITC Choupal Saagar—which functions as a hub for a cluster of villages within tractorable distance. These made-to-design hubs also serve as warehouses, and as rural hypermarkets for a variety of goods. In effect, the e-Choupal infrastructure is potentially an efficient delivery channel for rural development and an instrument for converting village populations into vibrant economic organizations. With the increased penetration of smart phone use, the company launched a mobile version in 2019 to make the program even more widely accessible and to support a broader range of services including crop management, farm mechanisation, healthcare, banking and insurance.

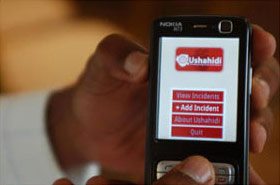

The best problem solvers are those who deliver what is needed at the highest quality and for the lowest price. The knowledge of how to do this is often accessible only to local insiders who can see what is needed, have the flexibility to adapt to changing conditions and, above all, the incentive and will to get the job done. In the violent aftermath of the disputed Kenyan presidential election in 2007, a young Kenyan David Kobia and his friends launched the nonprofit Ushahidi, Swahili for “Testimony” or “Witness.” Created over a weekend because they saw the urgent need for people to know which areas were violent, which were safe, or where to find resources like medical help and water, Ushahidi quickly acquired 45,000 users and the founders realized that it had potential. It enables anyone with a phone or Internet access to record, communicate and store events in real time, especially in areas of the world that may have difficulty connecting and sharing stories. It now expands over 10 time zones and has crowdsourcing maps in over 30 languages. It’s been used in a number of natural disasters such as Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, Hurricane Sandy that hit the Caribbean, Canada and the United States in 2012 and the Haitian earthquake that also happened in 2012. Among the events that have been reported using Ushahidi are power outages in India, sexual harassment incidents during the Arab Spring, gender-based violence in Pakistan, and hate crimes in South Africa.

Entrepreneurs can be flexible, adapt and make changes: Ushahidi also created Crowdmap, a hosted version of their platform with centrally located data, made for quick mapping with social media or the web when people need to get information out faster. When they saw that a major obstacle to their plans was reliable connectivity in the areas they wanted to reach, they created BRCK, a router device specifically designed for remote African locations. As Nathaniel Manning, their director of business operations says: “People from Nairobi are much better suited to design things for their communities and come up with solutions than someone in Silicon Valley who is no doubt brilliantly smart, but they don’t live with the problem.” Ushahidi now also provides technology consulting for clients such as Al-Jazeera, the World Bank, and the United Nations.

“People from Nairobi are much better suited to design things for their communities and come up with solutions than someone in Silicon Valley who is no doubt brilliantly smart, but they don’t live with the problem.”

Entrepreneurs are and will continue to make a significant impact on the continent of Africa. In 2015, 400 applicants from 30 countries entered the Forbes She Leads Africa Entrepreneur Showcase. The magazine selected “six early stage entrepreneurs who in just two years of operation have combined revenue of around $3m USD, more than 11,000 customers and represent various consumer goods industries including apparel, beauty, food and health.”

“Entrepreneurship empowers people to no longer be subject to aid agencies, but to be part of something to pursue their dreams. Entrepreneurs like you can change the world one idea at a time,” President Obama said during a White House event in May, 2015. However, less than one in four Africans have access to the training and money they need to start or grow a business by themselves, so this is certainly an area for investigation and support.

What can wealthy countries do to help foster grass roots entrepreneurship? This TED talk explains why top-down solutions are likely to miss their mark and create opportunities for corruption instead of economic growth. Wealthy countries should persuade governments to remove legal and other obstacles to the creation and success of small businesses.

Investing in the Poor

By providing opportunities to local people, companies encourage villages to become more self-reliant.

Low-income and poor communities can improve when large firms and multinational corporations provide quality goods and services. These may have to be adapted, often quite radically, to meet specific requirements, including hostile environments where only limited resources are available. As an example PRODEM (later Banco Sol) has introduced smart Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) in Bolivia that speak three local languages, providing high-quality financial services to illiterate customers.

By providing opportunities to local people, companies encourage villages to become more self-reliant. The Bank of Mandura, for example, set up self-help groups in southern India as a way of expanding its customer base. The bank teaches these groups how to hold meetings, keep records, and so forth, so that they can become responsible for all financial transactions with the bank. The number of self-help groups increased to 10,000 and served 200,000 families, and with the default rate on loans less than 1%, led to the bank’s merger with the Indian multinational Bank ICICI.

Prices have to come down dramatically to be affordable for low-income consumers. ICICI Bank in India is a corporation which provides financial services at a fraction of the cost of its competitors. It does this by lowering its administrative costs, serving 200,000 poor customers with only 16 managers. The bank grants loans to qualified self-help groups who in turn loan money to individuals and are responsible for repayment. In this way customers gain access to cheap, reliable capital and the bank makes a profit.

Since the poor tend to buy only what they need for the day, single-serve packaging has become very popular. Amul sells good quality ice cream in India for 5 cents a serving. The size of the Indian shampoo market is as large as the US market and Proctor & Gamble has started selling one of its high-end shampoo products in a single-serving sachet.

An estimated 12 million people are blind in India, the vast majority of them from cataracts. Aravind Eye Care performs high-quality cataract surgery for $50 to $300, and 60% of their customers pay nothing at all. The company designed a protocol using specially designed hospitals so that only one doctor and two technicians can perform over 50 surgeries per day. In order to adequately help the poor, Aravind needed to provide a permanent presence in rural areas. Some 36 storefront vision centers were established, staffed by rural women recruited and trained by Aravind. Using cameras, doctors are able to do eye examinations remotely. In 1992, Aravind set up Aurolab, which now manufactures sutures, medicines and lenses for $2 apiece. Aurolab is now a major global supplier of intraocular lenses and has driven down the price of lenses made by other manufacturers.

Access to distribution networks is still a challenge for the rural poor, but there are ways around it. In 1993, 320,000 Avon Ladies worked throughout Brazil, more than 60,000 of them in the Amazon.

A market-based ecosystem provides a framework for a variety of groups to work together provided they have the flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances as they strive for increased efficiency.

It’s essential for large firms to build trust between themselves and poor communities if they are to be successful. Companies whose personnel interact with their customers do better than those that outsource their delivery process. Bimbo, the largest provider of bakery products in Mexico, has developed such a high level of trust with it customers that its truck drivers often deliver their products and collect money without supervision. All Bimbo managers have to work as truck drivers first, so that they better understand their customers and can act as ambassadors for their company.

A market-based ecosystem provides a framework for a variety of groups to work together provided they have the flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances as they strive for increased efficiency. Hindustan Unilever Limited (HUL) is an ecosystem consisting of manufacturing plants, suppliers, distributors, wholesalers, retailers, and direct distributors. It also works with state governments to promote local farm products and provides access to global markets, establishing mutual obligations, and setting quality standards and ensuring a shared vision. According to the Center for Disease Control, diarrhea kills more children than malaria, measles, and AIDS combined. Simply teaching children in southern India to wash their hands with soap before eating can help to prevent childhood deaths from diarrhea. HUL had to work with state governments, NGOs, and the World Bank to create and implement a simple demonstration for schoolchildren to show that clean-looking hands can still contain harmful germs, which cause disease. They found that as children learn about better hygiene they pass this information on to their parents.

Microcredit

Too often the poor are unable to produce enough to survive, let alone have enough to live on. Low productivity means that there is no money to invest in those things that could increase output. Banks will not lend even the small amounts required to invest in the means to increase productivity because those on such low incomes can provide no security against the loan. The only money available is often from local moneylenders who charge exceptionally high interest rates that only make the situation worse.

In 1974, Professor Muhammad Yunus, a Bangladeshi economist from Chittagong University, sparked the beginning of a worldwide movement by lending $27 from his own pocket to 42 poor basket weavers. He subsequently set up the Grameen Bank to provide small loans to the poor at low interest to help start or improve a small business, provide for their families and escape the cycle of poverty.

As of November 2019, Grameen had 9.60 million members, 97 percent of whom are women. With 2,568 branches, GB provides services in 81,678 villages, covering more than 93 percent of the total villages in Bangladesh.

At every branch of Grameen Bank, the borrowers recite Sixteen Decisions and vow to follow them. Possibly the most important one is agreeing to educate their children by sending them to school. Since the Sixteen Decisions were incorporated, almost all Grameen borrowers have their school-age children enrolled in regular classes. This in turn helps bring about social change, and educate the next generation.

Solidarity lending is a cornerstone of Grameen microcredit. Each borrower must belong to a five-member group, though repayment responsibility rests solely on the individual borrower. The group and the center oversee that everyone behaves responsibly and none gets into a repayment problem. In practice the group members often contribute any defaulted amount with an intention to collect the money from the defaulted member at a later time. Such behavior is encouraged because Grameen does not extend further credit to a group in which a member defaults.

The success of this model has encouraged the growth of many more microfinance institutions in Latin America, Africa and Asia such as Kiva and PRODEM (later Banco Sol). The Grameen system is now used in more than 43 countries.

For people in extreme poverty, microcredit is not an option because they are unable to handle the demands of repaying a loan. One alternative is to provide them with a few farm animals, a small stipend and some training in tending the livestock and managing their household budget. Randomly chosen families participated in such a program run by Bandhan Development Program, an Indian microfinance institution. It was found that families were eating 15% more, earning 20% more, and saving more money than comparison groups, long after the financial assistance ended. These results were so much better than expected that they could not be directly attributed just to the grants. Researchers concluded that the program had cut the rate of depression so sharply that beneficiaries were more optimistic, began working harder and started looking for new opportunities to improve their lives. Giving people hope helped them break out of poverty.

Although microfinance is challenged now by over-application, administration of the loan APS (application processing system), high interest rates, and various dole-out and pay-back schemes, some entities have begun credit-worthiness checks on potential recipients, helping to drive down the cost of loans by reducing the risk.

Technological Solutions

As Easterly says, aid involves “systems that nobody designed, that display order that nobody ordered, and that deliver outcomes that nobody intended.” Today much economic growth happens through technological innovation, which cannot be planned or predicted. It takes many individuals trying many different things to find the best way of doing things, and no one knows in advance which solutions will be successful. The invention of the cell phone is perhaps the best recent example. Today a farmer can take a photograph of a diseased crop, send it to a lab hundreds of miles away, and receive expert advice. Before cell phones African farmers and fishermen had to travel from market to market or lose money to a middleman. Now these producers of high-end coffee and cut flowers are linked to the world themselves, they can call around from their boats or fields to different markets and get the best price, and use their cell phones to transfer money instead of using inefficient banks.

Poor countries that provide individuals with incentives to innovate can catch up by adopting new technologies.

Easterly’s finding asserts that “Technology is a principal determinant of income per capita.” Poor countries that provide individuals with incentives to innovate can catch up by adopting new technologies. Governments have begun to use information technology to provide better access to information and make transactions transparent. For example, things changed dramatically once the government of the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh in collaboration with the private sector, provided better access to its services by using the Internet. A semiliterate farmer previously had to go through a broker to register his land. The land registration process now takes one hour, instead of seven to fourteen days; title searches take fifteen minutes, instead of three days; and the system calculates the price of land based on fair market value, instead of arbitrary assessment.

Andhra Pradesh has made over 45 government services available to the public in this manner. It used to take at least half a day to go to the electric department to pay the monthly electric bill. Now people can conduct all of their transactions at one time at nearby kiosks without having to pay “speed money.” The system records each transaction to prevent corruption and, for the first time, citizens receive the same level of service regardless of their economic class.

The Center for Good Governance has been set up to monitor the system in Andhra Pradesh. It publishes reports and makes recommendations on what needs to be changed and has established a performance monitoring system which evaluates government officials. The chief minister holds a monthly teleconference with more than a thousand government employees as well as the press. District administrators must explain negative trends and what actions they are taking to improve the situation. This level of transparency is forcing government officials to focus on what is important to the citizens in their district.

Again, bringing telephone services to the rural poor makes a huge difference all over the world. Grameen provides one borrower in each village with a cell phone. These “telephone ladies” earn a substantial living by selling the telephone service to other villagers enabling everyone to connect with the world, conduct business over the phone instead of sending a messenger, and to stay in touch with families and friends.

Investments in Health

…accelerated training programs [in health care] for young people are already being implemented in Afghanistan and Ethiopia.

Most poor countries still face a shortage of skilled workers, so innovative solutions must be found to improve their lives. The World Health Organization warns that without new training models for health professionals, there is little chance of meeting the Sustainable Development Goal of universal health coverage by 2030. It recommends expanding and modernizing training to equip millions of young people with the skills needed to join the health workforce. While concerns about quality and oversight remain, accelerated and blended training programs for young people are already being implemented in countries such as Afghanistan, where intensive community health volunteer and graduate training schemes have begun, and Ethiopia, where the Ministry of Health has adopted a blended learning model for more than 40,000 Health Extension Workers.

In Peru, Voxiva has developed a medical diagnostic system that enables low-skilled health workers in remote areas to identify illnesses using numbered picture cards. Health workers just telephone their findings to officials in Lima using a card with simple instructions and numbers corresponding to the diseases they must report.

The Mobile Technology for Community Health MOTECH is an open source software project delivered by Grameen Foundation. It is adapted to facilitate communication between patients, caregivers, and/or health administrators, providing health solution via mobile phone. It communicates to patients or caregivers via voice or SMS supporting the sick as well as pregnant and young mothers, reminding them of appointments, lab visits, to take medication, to report symptoms prior to treatment, and so on. Through it caregivers can be given a basic training in diet, nutrition and basic health requirements, immunization, etc., so that they can visit people in their communities and share this information.

The poor make use of new products and services in unexpected ways. Farmers in India use the internet to chat with their friends, watch movies, and listen to music. They print out their children’s school grades, track global price futures, and use email to get answers on agricultural problems. Women from different villages meet in virtual chat rooms to discuss political and social issues.

Providing clean water and sanitation are elementary effective investments in health; diarrhea can be reduced by up to 95% by providing households with clean drinking water.

As we have seen with Ushahidi and Unilever, solutions to problems and innovations developed in one local market can often be applied to similar markets globally. The Food and Drug Administration and the Center for Disease Control in the US are now testing the system that Voxiva developed for monitoring infectious diseases in rural Peru.

Providing clean water and sanitation are elementary effective investments in health; diarrhea can be reduced by up to 95% by providing households with clean drinking water. Yet, according to the latest WHO/UNICEF data, roughly 2.2 billion people still lack safely managed drinking water access, 3.5 billion lack sanitized toilets, and half a million children under 5 die from diarrhea every year. Most of these deaths can be prevented by inexpensive, simple solutions, like adding chlorine to drinking water. In India’s villages, the cost of providing tap water and a toilet is about $4 per household: this small investment could reduce severe diarrhea by half and malaria by one-third. A bottle of chlorine costs about 18 cents and lasts for about a month, but only 10% of the population in Zambia use it to treat their water. If villagers cannot afford to pay, governments and aid organizations need to step in to subsidize the cost. At the same time, education is necessary so that people clearly understand both the value and application of such interventions: in India, many children die from dehydration because mothers don’t believe that a packet of oral rehydration solution will do any good.

Most successful health initiatives are programs run by aid agencies with the cooperation of local authorities and local health workers. Vaccination programs and programs to eliminate pests are prime examples. But health-care systems are difficult to setup and maintain. They are generally inefficient and merely expanding them would, according to the economist Angus Deaton and others “simply mean more clinics that are open irregularly, more officials diverting funds, and more health-care workers being paid not to do their jobs.” Plus, money spent on health care in poor countries is too often used to treat the urban elite while “children die from diseases that could have been treated for a few cents or avoided altogether with basic hygiene practices.”

The importance of immunization is hard for people to understand, because it is difficult to make the link between treatment and absence of disease. Providing incentives can make a difference.

The Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization will buy drugs that are needed in developing countries to give drug companies the needed push. As a result, again according to Deaton, “Children are now being immunized in ten countries against pneumococcal disease, which currently kills half a million children each year.” The importance of immunization is hard for people to understand, because it is difficult to make the link between treatment and absence of disease. Providing incentives can make a difference. When villagers in India were given two pounds of dried lentilsfor each immunization and a set of stainless-steel food plates for completing the course, immunization rates increased from 6% to 38%. People should have easy access to the medicines they need and restricted access to the medicines they don’t need, so that drug resistance is prevented.

Growing populations put additional stress on the environment and further diminish scarce resources.

Many parents in poor countries rely on their children to take care of them in their old age, and having a large number of children increases the likelihood that at least one of them will do so. More than half of the elderly in China live with their children. Most parents invest less in daughters because sons are more likely to care for them in their old age. The result is that in some regions of China, there are 130 boys to 100 girls.

Growing populations put additional stress on the environment and further diminish scarce resources, such as clean water. Women tend to adopt contraceptive practices that conform to the social and religious norms of their community, which means that even when women have a choice, relatives and social norms pressure them to have more children that they would like. In areas that have family planning clinics, fertility rates are lower because even discussing the issue with female health workers lowers the number of children women wish to have. When women have access to contraceptives without their husband’s knowledge, fertility rates drop and the number of unwanted births decreases. Educated women and women who own property are in a better negotiating position with their spouse and family, because they are better able to find a job should the marriage end in divorce. Fertility rates dropped in Peru when women’s names were added to property titles. Changing cultural attitudes via the media has shown some success: after soap operas became popular in Brazil, birth rates dropped to levels more in line with the female characters in the show.

Pregnancy rates are very high in developing countries where contraceptives are not available.

A simple step like making school uniforms free to teenage girls has been shown to decrease teenage pregnancies and encourage girls to stay in school. Of course, access to contraceptives makes a bigger difference: pregnancy rates are very high in developing countries where contraceptives are not available. Adolescents can make smart choices if they are fully informed and able to avoid sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy. Unfortunately, in too many schools, children are told about abstinence, but pregnancy prevention methods, such as condoms, are not discussed.

Although it’s possible that programs which provide for the elderly would make it unnecessary for parents to have so many children, family decision-making is a complicated process that does not always result in what is best for the family. Studies of family farms show that programs that remunerate women benefit the family more than those which pay men. Nevertheless, more resources are allocated to men in spite of the fact that they spend more money on alcohol and tobacco when their crops do better, and women spend more money on food when theirs do better.

The Way Forward

It’s clear that any long-term solution to the problem of global poverty requires addressing the underlying issues of inequality and insecurity.

Creating a More Equitable Economy

As former President Barack Obama said in his final address to the United Nations in 2016, “A world in which one percent of humanity controls as much wealth as the other 99 percent will never be stable.”

“A world in which one percent of humanity controls as much wealth as the other 99 percent will never be stable.”

According a January 2020 Oxfam report on the global inequality crisis, Time to Care, the world’s billionaires—just 2,153 people—have more wealth between them than 4.6 billion people.

The report shows how our broken economies are funneling wealth to a rich elite at the expense of the poorest in society, the majority of whom are women.

- In 2019, the richest 1% had twice as much wealth as 6.9 billion people.

- The monetary value of women’s unpaid care work globally for women aged 15 and over is at least $10.8 trillion annually—three times the size of the world’s tech industry.

- If you saved $10,000 a day since the building of the pyramids in Egypt you would have one-fifth the average fortune of the 5 richest billionaires.

As former Oxfam executive director Winnie Byanyima wrote in 2017, “It is obscene for so much wealth to be held in the hands of so few when 1 in 10 people survive on less than $2 a day. Inequality is trapping hundreds of millions in poverty; it is fracturing our societies and undermining democracy.

“Across the world, people are being left behind. Their wages are stagnating yet corporate bosses take home million-dollar bonuses; their health and education services are cut while corporations and the super-rich dodge their taxes; their voices are ignored as governments sing to the tune of big business and a wealthy elite.”

Business leaders can make a start by committing to pay their fair share of tax and by ensuring their businesses pay a living wage.

Some of the world’s billionaires have made comittments to dedicating their fortunes to finding and implementing solutions to the world’s most pressing issues.

Oxfam’s Even It Up! campaign calls on business leaders to play their part in building a human economy. In 2017, the World Economic Forum highlighted responsive and responsible leadership as its key theme. Business leaders can make a start by committing to pay their fair share of tax and by ensuring their businesses pay a living wage. People around the global can also join the Oxfam campaign.

Ensuring Stable Societies and the Rule of Law

According the World Bank, insecurity remains a central development challenge. By 2030, FCV countries (those affected by fragility, conflict, or large-scale organized criminal violence) will be home to up to two-thirds of the world’s extreme poor. While some low-income fragile and conflict-affected countries have made progress toward achieving certain Sustainable Development Goals, many continue to face significant challenges in meeting these targets.

Governments, aid and humanitarian organizations now understand that there is a definite correlation between rule of law and socio-economic performance. The world’s poorest people are suffering the most from the effects of crime and corruption, both of which severely challenge international and local efforts to successfully address the problems of the poor.

On September 25th 2015, the 193 UN member countries adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, with a set of 17 goals to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure prosperity for all.

These came into force on January 1, 2016. As with the earlier UN Millennium Development Goals established in 2000, each of these newly established goals has specific targets to be achieved by 2030.

Goal 16 is dedicated to “the promotion of peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, the provision of access to justice for all, and building effective, accountable institutions at all levels.”

UN facts and figures supporting this goal:

- In 2024, loss of lives amid armed conflicts surged 40 per cent from 2023, marking the third consecutive annual rise.

- About four times more children and women were killed in 2023–2024 than in the previous biennium; of these, 8 in 10 child deaths and 7 in 10 female deaths occurred in Gaza.

- Rising conflicts and violent organized crime persist around the world, causing immense human suffering and hampering sustainable development.

- In 2021, the world experienced the highest number of intentional homicides in the past two decades.

- Globally, detected human trafficking victims increased by 25 per cent in 2022 compared to pre-pandemic levels and by 43 per cent compared to 2020. A key driver of this surge is the growing number of child victims, which has risen by 31 per cent since 2019.

- Killings and disappearances of human rights defenders, journalists and trade unionists remained alarmingly high in 2024, with at least 502 killings documented across 44 countries and 123 disappearances documented across 37 countries.

- Structural injustices, inequalities and emerging human rights challenges are putting peaceful and inclusive societies further out of reach.

The stated targets of Goal 16:

- Significantly reduce all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere

- End abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children

- Promote the rule of law at the national and international levels and ensure equal access to justice for all

- By 2030, significantly reduce illicit financial and arms flows, strengthen the recovery and return of stolen assets and combat all forms of organized crime

- Substantially reduce corruption and bribery in all their forms

- Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels

- Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels

- Broaden and strengthen the participation of developing countries in the institutions of global governance

- By 2030, provide legal identity for all, including birth registration

- Ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms, in accordance with national legislation and international agreements

- Strengthen relevant national institutions, including through international cooperation, for building capacity at all levels, in particular in developing countries, to prevent violence and combat terrorism and crime

- Promote and enforce non-discriminatory laws and policies for sustainable development

Impact of Social Media

Access to social media has changed the world. It helped to facilitate an explosion in the Middle East. In the aftermath of the Arab Spring, it played a central role in shaping political debates and in the spread of democratic ideas across international borders. The opportunity and freedom to express oneself and connect with hundreds of like-minded people is revolutionary. But the positive effects of the Arab uprising were short-lived in part due to lack of experience and political structure upon which to build new institutions.

Social media also strengthened and extended terrorism, which now stretches from West Africa through the Middle East and into South Asia. Terror, terrorism and authoritarian misrule have caused the largest humanitarian crises in our history.

It’s not surprising that Freedom House reports that global freedom declined for the 19th consecutive year in 2024. Authoritarian regimes appear to have abandoned moves towards a freer society in their effort to defeat terrorism and preserve political control. Government corruption and ineptitude, together with the lack of freedom exacerbates the problem. Freedom House notes that “Armed conflict, attacks on democratic institutions by elected leaders, and deepening authoritarianism drove a large part of the decline in global freedom in 2024. Though serious, these phenomena are not new. . . As the world approaches two full decades of declining freedom, it is clear that new solutions—and far more vigorous and comprehensive efforts—are needed to address these persistently expanding threats to the security and survival of democracy. Should the current global trends continue, not even the most powerful democratic states will be able to guarantee the freedom and prosperity of their people.”

Nevertheless, people have to survive and will find ways—often totally unexpected—to do so. The road to successful economic development varies with each country and community depending on its unique history and culture. Growth can fluctuate over time, but studies show a number of common elements: Self-reliance and a willingness to search for solutions; market feedback and accountability; the ability and freedom to integrate Western ideas, institutions, and technology as needed.

By focusing on utopian goals, aid agencies have missed many opportunities to achieve realistic ones.

Governments need to be responsible for larger programs such as infrastructure, education, and security; but nevertheless, these need to be administered at the local level to avoid causing inadvertent harm to the very people they wish to help, and to ensure that useful developments are not only initiated and carried out, but maintained.

People often think of global poverty as a problem that is too big to solve. However, like most big problems, it can be broken down into a number of smaller ones. By focusing on utopian goals, aid agencies have missed many opportunities to achieve realistic ones. Of course international aid agencies like Oxfam, the Red Cross, the Red Crescent, UNHCR, and International Rescue Committee are indispensable when disasters like earthquakes, floods, and the sudden influx of refugees occur. Foreign aid cannot end poverty but it can relieve the suffering of the poor, and aid agencies should aim at this, instead of trying to change governments. By improving opportunities for health and education the poor have a chance of a better life.

Most importantly, listening to the poor and providing them with more choices, access to modern technology and quality products designed with their needs in mind adds to their quality of life. Steps like these not only help at least some get out of poverty, they can also improve the self-esteem of the community, eventually empowering people to demand the political changes they need.

listening to the poor and providing them with more choices designed with their needs in mind adds to their quality of life.

The poor live daily with a horrendous level of violence with no recourse to justice or the rule of law. They have limited access to information and education and next to no opportunity to use their talents. To be effective, global aid must address their real and changing needs. To help the poor, it is important to understand how they live, what they think, and what they need in each distinct community and location.

The free market favors the rich and powerful, but doesn’t provide economic opportunities for the poor, who don’t want charity, which undermines their self-determination. Many already have skills to earn money, or could acquire them through minimum training. Foreign aid agencies spend billions on development, but very little of it is spent on microcredit programs although the microcredit business is both profitable and beneficial not only to the poor, but to society at large.

The free market favors the rich and powerful but doesn’t provide economic opportunities for the poor.

Aid agencies need to invest in entrepreneurs whose products will help the poor. They need to invest in technologies and training so that, for example, communities can be connected by phone and able to organize to ensure that their voices are heard, that their women and children are safe, and that services work in their communities.

As Barack Obama told audiences at the Global Entrepreneurship Summit in 2015 in Nairobi, Kenya, “Entrepreneurship creates new jobs and new businesses, new ways to deliver basic services, new ways of seeing the world – it’s the spark of prosperity. It helps citizens stand up for their rights and push back against corruption. Entrepreneurship offers a positive alternative to the ideologies of violence and division that can all too often fill the void when young people don’t see a future for themselves. … in order to create successful entrepreneurs, the government also has a role in creating the transparency, and the rule of law, and the ease of doing business, and the anti-corruption agenda that creates a platform for people to succeed.”

External Stories and Videos

Innovative Solutions to Poverty and Hunger

The Borgen Project

Explore some of the many inventions Improving conditions for people in the world’s poorest regions.

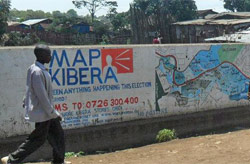

Map Kibera

Map Kibera

Map Kibera was born in the Kibera slum of Nairobi but is growing to connect marginalized communities across the whole of Kenya’s capital. They use OpenStreetMap, a free, editable program to map local amenities and resources, particularly services that address security, water sanitation, health and education. Their mappers are all young community members who use GPS devices to collect data, and computers to edit and upload the map information, ensuring that all the information is kept up-to-date.

Mapping may include surveys of the general features of a district – like pathways, clinics, water points and markets – or might get into a great deal of detail in one subject – say, health mapping of a given area. In that case, surveying can include not just pharmacy locations but also hours of operation, the kinds of services offered and other much-needed public information.