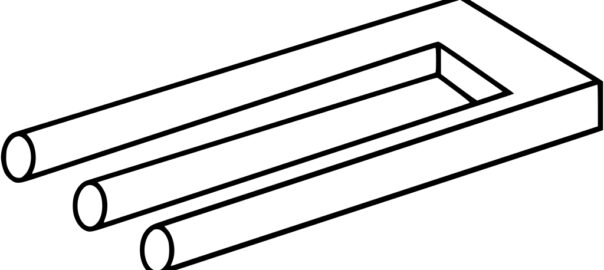

The Devil’s Tuning Fork

Sally Mallam | October 26, 2022

In the late fifties/early sixties my sister and I spent summer holidays in East Africa in what is now Tanzania. My father was a British Colonial Officer in the Tanganyika Forestry Department.

We had servants and my mother constantly complained about their deficiencies. One repeated incident concerned rugs that were never replaced correctly after being cleaned—they were always crooked. She took this to be evidence of either insolence or stupidity, which fed into a common assumption among non-Africans of white superiority. After all, she had taught the houseboy how to place the rugs. He’d taken them outside, brushed them well, but then brought them back and laid them down—crooked again!

A decade later, I was in Niger in West Africa, working on a project in Niamey. In conversation with an Italian architect and builder who had emigrated there, I asked him how easy it was to work with the local people. “No problem at all,” he said, “just as long as you remember that many of them have grown up in a non-carpentered world, often in round huts. They don’t experience straight lines as strongly as we do. So don’t ask them to hang doors or windows.” Or presumably, I thought, to lay rugs down straight the way my mother liked. This was such a useful lesson, and it stayed with me, of course.

There’s so much more information on our human nature available now than there was 50 years ago. To share some of it is why we created The Human Journey website. For example, we know now that 75 percent of the human brain develops after we’re born. That’s one reason why individuals from different cultures have such difficulty understanding each other. That explains my story and others that we refer to on the website from Malaysia and Zimbabwe, the wonderful tale by the anthropologist Colin Turnbull of the Mbuti pygmy, and the crazy drawing shown above, known to some as the “impossible trident” or “devil’s tuning fork,” that most people brought up in the West cannot reproduce.

But the crucial difference between us of all, I think, lies in the diversity of our minds—how we each uniquely understand and experience the world. Again, because most of our brain and mind develop outside the womb, we view the world through our personal interpretation of experiences and memories of them. Ask my sister about our time in Africa, and she has completely different memories; and where we do share a common recall, her interpretation of an event is never the same as mine.

Of course, we humans have evolved common characteristics. We are all bipedal and feel and express the same basic emotions. We share the same planet, see the same sky, walk on the same earth.

Also, all of us share a cultural history with others and are affected by our community’s passed-down memories: the holocaust; the “Middle Passage” of slave ships, the conquest of America; the success of a recent ancestor’s company or invention. I’ve lived in the US for more than 38 years, yet there is still a certain affinity I have, a certain basic communication I share, when I bump into someone from England.

These three considerations form our normal everyday consciousness. Not knowing this, or not remembering it, we tend to react in ways that are no longer appropriate. We assume that we know and understand another’s worldview; that it’s sufficient to categorize people by class, ethnicity, sex, culture or color.

Generalizations may have worked fine while we lived in small bands or tribes. By forming collaborative groups back then we survived enormous obstacles including the freezing Ice Age. Differentiating between us and them made sense then, and it is hardwired in us today. We are born with the ability to judge who’s “like me” and who isn’t. But the world we’ve made is not the same as when we became modern man—homo sapiens. As one of my favorite authors Idries Shah writes in his book Reflections, “Tolerance and trying to understand others, until recently a luxury, has today become a necessity.”

Characteristics developed to survive in the late Stone Age, still hang on today. Some are no longer appropriate and cause problems. Others, such as our capacity to adapt and our extraordinary ability to connect and collaborate, are what we need right now. This combination enabled us to change the world and live anywhere on the planet. We have increased our numbers to almost 8 billion people and doubled our lifespan, but we’ve failed to consider the long-term effects of doing so.

The crucial problems that we need to solve today are global, and to do so we need a different mindset. One that recognizes that we all live on one globe and that it—and our human future—depend upon our ability to understand, connect and collaborate with each other for the sake of all.

It seems to me that it’s time now to consider, in the words of the late psychologist Robert Ornstein, that “The greatest surprise of human evolution may be that the highest form of selfishness is selflessness.”

Sally Mallam is the current executive director of The Institute for the Study of Human Knowledge and executive editor of The Human Journey project. She directs ISHK’s literacy outreach programs. Mallam is also the author of The Human Journey’s comprehensive overview of the impact of religious ideas throughout history.

Recent Blogs

- An Old Story About Metaphysics

- The Conditioning Machines in Our Back Pockets

- Out on a Limb: The Danger of our Innate Shortsightedness

- Edward T. Hall: Culture Below the Radar

- The Half Brain Method

- 'He Who Tastes Knows': Contemporary Sufi Studies and the work of Idries Shah

- "They Saw a Game"

- A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Enlightenment

- Finding the Right Way Home

- Time and Self

- Escaping the Either/Or Thinking Trap

- Looking Up, Looking Out

- Conditioning and the Gendered Brain

- New World, Same Mind?

- One Small Word

- Meaning: The Enduring Gift to Spirit

- Beyond East and West: Human Nature and World Politics

- Forest Smarts: A Part of or Apart From?

- How to Improve Group Decision-Making

- We Know More Than We Think We Do

- How Deep Can a Story Go?

- Lost and Found: An Encounter with the Intuitive Mind

- The Devil’s Tuning Fork

- Welcome to The Human Journey Blog